AONN1756-2

The past few years have marked a major step forward in how patients with blood cancers like lymphoma and leukemia are diagnosed and treated. With more than 30 new types of treatments approved for blood cancers in the past 5 years alone, oncologists are working hard to keep up with all the new medical advances. To do so, they learn from a variety of sources, including research articles and continuing education courses.

People who have been diagnosed with cancer also have much to learn. The Institute of Medicine has suggested that the quality of cancer care improves when people who have been diagnosed with cancer play an active role in decisions related to their treatment.1 In addition, surveys of patients with cancer have shown that most patients prefer to play an active role in their treatment choices.2,3 Not surprisingly, patients with cancer are less satisfied with the quality of their care when physicians determine on their treatment without their input.3 That doesn’t mean you need to understand all the complicated science behind medical decisions—oncologists are trained to do just that. However, you know yourself best, and it is important that you let your treatment team know about the things that are important to you.

Before we discuss your role in working with your treatment team, let us review the major types of blood cancer and the medications used to treat them. We then take a closer look at how your oncologist decides which treatment options are best for you, and how you can provide your input throughout the entire cancer journey.

Types of Blood Cancer

Most blood cancers can be sorted into 1 of 3 categories, depending on the type of white blood cells that are affected, including leukemia, lymphoma, or multiple myeloma.4 Because white blood cells are a key part of the immune system, all types of blood cancer can weaken the body’s ability to fight infection (and other diseases), although this happens in a different way for each type of blood cancer.

Leukemia is a type of blood cancer that involves an overgrowth of white blood cells, which are immune cells that are normally found in the blood and bone marrow. When there are too many white blood cells, the body has a hard time fighting infection and making other types of blood cells, such as red blood cells. Leukemia can be classified as “acute,” meaning it is fast-growing, or “chronic,” meaning it is slower-growing.

Lymphoma is a type of blood cancer that involves the lymphatic system, which removes extra fluids from the body and protects against infections. Lymphocytes are a major type of white blood cell found in the lymphatic system and in the blood. In lymphoma, these cells multiply out of control, which eventually causes swelling of the lymph nodes and sometimes other tissues, including problems with normal immune system function. Different kinds of lymphoma are named by the specific type of lymphocyte involved, such as T-cell lymphoma or B-cell lymphoma.

Multiple myeloma is a type of blood cancer involving plasma cells, which are a type of white blood cell found in the bone marrow and blood. When plasma cells grow out of control, they alter the development and function of other blood cells, such as red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

Common Types of Medications for Blood Cancers

There are 3 types of medications that are usually used to treat blood cancer. Because not all blood cancers are the same, certain medications may work for some types of blood cancer and not others. Also, medications may become less effective over time, which means that some patients will need to switch medications during their treatment. In addition, different kinds of medications may be used together to improve their impact.5

These factors are important to keep in mind when you and your oncologist are choosing the best treatment for you. Although surgery may be an option for some patients with blood cancer, solid tumors are not as common in blood cancer as they are in other types of cancer, which makes surgery less likely.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is an older type of cancer therapy, but it is still effective in fighting cancer for some patients. It works by directly killing cancer cells or stopping them from multiplying. Chemotherapy often harms healthy cells as well as cancer cells, which explains some well-known side effects of chemotherapy, such as hair loss, nausea, and diarrhea.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a newer type of cancer therapy that boosts the immune system, helping it to kill cancer cells. Immunotherapy includes treatments that work in different ways. Some boost the body’s immune system in a very general way. Others help train the immune system to attack cancer cells specifically.

Immunotherapy is used by itself for treating some cancers, but in other cancers, it works better when used in combination with other types of treatment.

Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapy is another type of new cancer medication. As the name suggests, medications in this class are designed to hone in on a specific target, which is usually a unique feature of the type of cancer cell being treated.

The goal of the targeted therapy is to limit harm to your healthy cells during treatment and to reduce the medication’s side effects. Targeted therapies must match with the exact type of cancer to be most effective.

The Role of Mutations in Causing Cancer

Like other cancers, blood cancers can be further described by the types of abnormalities found in the genes of the cancer cells involved. In simple terms, genes serve as the operating instructions for cells, telling them how to behave and multiply. When genes are abnormal, or “mutated,” cells get the wrong instructions, which may cause them to behave and multiply abnormally. Cancer happens when these mutations cause cells to grow too quickly and live too long. Today, blood cancers are often being treated based on these gene mutations, using targeted therapies to pinpoint and destroy the cancer cells that express them.

Genetic Testing to Guide Treatment

To check for gene mutations, genetic testing is performed in a lab, using a tissue or fluid sample. This may be blood, bone marrow, or a piece of a tumor, depending on the cancer type and location.3 There are several types of genetic testing. One of the newer, more advanced types is called “molecular profiling.” With the test results, oncologists can match certain mutation types with specific targeted therapies, which can sometimes provide better outcomes than older treatment, such as chemotherapy.5,6

Think of the treatment as a cop, and the cancer cell as a robber who has gone into hiding. Previously, we could only tell the cop the name of the neighborhood in which the robber was hiding. Today we can use genetic testing to find the exact house address. But cancer is a very sneaky robber, and when the cop starts knocking on the front door, the robber can change appearances or even sneak out the back door to another house, escaping arrest. This is where drug resistance comes in.

Drug Resistance

With all this new research and technology, do you ever wonder why we haven’t cured cancer yet? One of the reasons is “drug resistance,” which happens when a cancer doesn’t respond to treatment with a specific drug.7

In some cases, cancer can be resistant to a drug from the start, so that the first treatment doesn’t work. In other cases, drug resistance can develop over time. Resistance happens in several complicated ways, some of which we are still trying to understand fully.

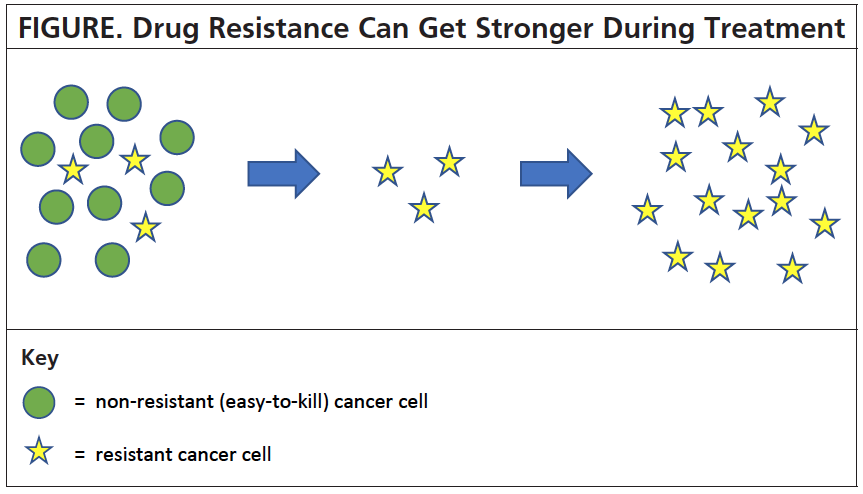

One of the simplest ways is: In the beginning, a treatment may destroy most of the cancer cells, which are easy to kill, leaving only a few resistant cells behind. After the easy-to-kill cancer cells die off, a patient may feel better, but it doesn’t last. Over time, that little group of resistant cancer cells multiplies into a big group, and soon enough, resistant cancer cells have replaced all the easy-to-kill cancer cells, and the drug doesn’t work anymore. A simplified version of this type of resistance is shown in the Figure.

Drug resistance can be hard to predict, because resistant cancer cells can multiply slowly or quickly. Sometimes, they can remain hidden for a long time before they start multiplying again (this is called “indolent cancer”).

Drug Resistance and Genetic Testing

One of the main reasons for genetic testing is to detect drug resistance, so that you don’t have to take a medication that may not work for you.7 But here’s a key point to keep in mind: Because cancer may change over time, with new mutations developing in response to treatment, what worked in the beginning may not always work. In other words, many patients will need to have genetic testing more than once.

Many patients with blood cancer should have genetic testing performed when they are diagnosed, and if the disease progresses during treatment. In addition, there is now evidence to support testing on a routine basis as a form of monitoring, to catch mutations early so that the medications can be changed as soon as needed.8

Consider Your Treatment Options

You and your oncologist have much to think about when you are deciding which treatment options may be best for your specific situation. It is your oncologist’s job to understand your disease and genetic factors when recommending treatment, taking these factors into account:

- Your age and overall health

- Any previous cancer treatments

- Is the cancer stable or progressing?

- Expert recommendations (treatment guidelines)

- Possible treatment side effects

- The type of blood cancer

Of course, your personal and family needs and goals are also important. This includes your employment status and whether you need to work; your personal beliefs and goals; your ability to travel long distances for treatment; and your support network, such as family and friends.

For example, many new cancer drugs are available as pills taken by mouth, called “oral drugs.” Patients taking these oral cancer drugs may need fewer trips to the cancer center than those who receive chemotherapy by IV injection. However, taking oral drugs may also mean higher out-of-pocket costs than using chemotherapy, depending on the patient’s health insurance.

Take Action

Knowledge is power, and this applies to doctors and to patients. Reading articles is a great way to learn about testing and treatment options, but it isn’t the only step you need to take. The next step is putting your knowledge to work, which means participating in the decision-making process with your doctor.

As a part of this process, ask your oncologist about your specific type of blood cancer, genetic testing, and your treatment options. Specifically, you can ask how your doctor will be using the results of genetic testing to choose the best treatment. And don’t be shy about asking to review the results with your doctor, with explanations of what each result means.

Tom’s Example

To understand how you can benefit from genetic testing, here’s an example of a patient named Tom, a 74-year-old grandfather from Russell, Kansas.

Tom loves to play with his grandkids, but over the past few months he’s had increasing trouble keeping up. On top of this, he’s been losing weight, and fast—15 pounds over the past 4 months. Tom was diagnosed with high blood pressure a few years ago, but this time, when he made the appointment to see his doctor, he was worried that something more serious might be going on.

Tom’s instinct was right. During a physical exam, his doctor found that his spleen and lymph nodes were swollen, and a routine blood test found an unusually high number of white blood cells in his system.9 Based on these findings, another blood test was performed (flow cytometry), which showed that Tom had a type of slow-growing blood cancer called chronic lymphocytic leukemia (or CLL). With this information, Tom’s doctor referred him to an oncologist for further testing and treatment options.

Although Tom’s diagnosis was difficult to process, he did as much reading as he could about CLL before his appointment with his oncologist. He learned that these days, patients are encouraged to play an active role in decision-making with their doctor, and doctors are trained to consider patient goals and wishes.10,11 So when the time came for questions, he simply asked, “Will you order a genetic test to see which treatment might work best for me?”

Fortunately for Tom, his oncologist kept up with the latest research. She confirmed that she would be testing him for mutations. A week later, when they were reviewing the blood test results, Tom’s oncologist said that he had the del(17p) mutation.

She explained that there was a specific type of targeted therapy that was a good option for patients like him. Research has shown that patients like Tom did better when they started with this medication than with other options.2 After discussing possible side effects, Tom and his oncologist decided together that this therapy was the best choice for him.

Conclusion

Aside from the initial shock of a cancer diagnosis, patients have a daunting amount of information to learn and process about the disease. In addition, navigating the complex healthcare system presents other challenges for patients and their loved ones.

People who are diagnosed with blood cancers need to learn enough without being overwhelmed and participate actively in their treatment decisions. It is vitally important to communicate important personal information about you, because it can affect your treatment decisions.

For most people with cancer, it is a marathon, not a sprint. Take time to learn how to interact best with your treatment team. Be kind to yourself as you absorb and sift through all the new information. As you gain knowledge, you will feel more empowered to ask questions, discuss treatment options, and participate in the decision-making process with your doctor.

References

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

- Keating NL, Guadagnoli E, Landrum MB, et al. Treatment decision making in early-stage breast cancer: should surgeons match patients desired level of involvement? Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(6):1473-1479.

- Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Arora NK, et al. Association of actual and preferred decision roles with patient-reported quality of care: shared decision making in cancer care. JAMA Oncology. 2015;1(1):50-58.

- American Society of Hematology. Blood Cancers. www.hematology.org/Patients/Cancers.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma. Version 2.2020. October 8, 2019.www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cll.pdf.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Version 2.2020.September 3, 2019.www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/aml.pdf.

- Housman G, Byler S, Heerboth S, et al. Drug resistance in cancer: an overview. Cancers (Basel). 2014;6(3):1769-1792.

- Schuh A, Becq J, Humphray S, et al. Monitoring chronic lymphocytic leukemia progression by whole genome sequencing reveals heterogeneous clonal evolution patterns. Blood. 2012;120(20):4191-4196.

- Davids MS. A case review of a 74-year-old man with CLL. Targeted Oncology. April 26, 2019. www.targetedonc.com/case-based-peer-perspectives/chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia/davids-cll-ighv-unmutated/a-case-review-of-a-74-year-old-man-with-cll.

- Fried TR. Shared decision making — finding the sweet spot. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374(2):104-106.

- Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making — the pinnacle of patient-centered care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(9):780-781.