“The challenge is to kill the tumor, without killing you.”

No one told me much about my esophagus, yet there it was, front and center, a lead player for the rest of my life. The esophagus is the tube that moves swallowed food down to the stomach. Better learn to spell it and pronounce “Ee-so-pha-geal.” Hit the “ge.”

Introducing Esophageal Cancer

Esophageal cancer is uncommon in the United States, accounting for only about 1% of all new cancer diagnoses, according to the American Cancer Society. The standard treatment for early stages includes radiation therapy. Patients often fear radiation more than the cancer itself.

My radiation oncologist welcomed me to her office and to her computer, which was alive with brightly colored lines dancing around the screen. She told me about the history of research on treatments for esophageal cancer. Charts and diagrams with lush vivid colors wiggled across her computer screen as she spoke. It turns out that her son developed the program in color.

The goal is to deliver radiation directly to my tumor, without harming the nearby organs. Think about that for a minute. The body above the waist is a high-traffic area with major organs—including the heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, and stomach—all nicely wrapped in the rib cage.

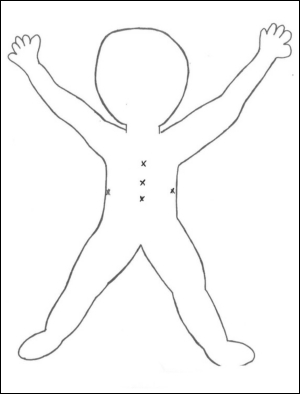

The computer screen showed how 5 radiation paths entering my body from 5 different angles (see Figure) would hit the tumor, and only the tumor. The gaily colored waves zooming across the charts showed how much radiation might be absorbed by neighboring organs, as radiation beams pass beside or over their edges. The paths showed that any damage to neighboring organs would be minimal. My treatment plan would include 28 sessions of daily radiation therapy.

I Was Hooked

I was hooked, seduced by those glorious colors, dazzled by the science. It felt like a great adventure. I couldn’t wait to get started. Sound crazy? Maybe, but here’s the point: with cancer, do whatever works to get through. Maybe even fool yourself a bit. We all cope in different ways. The magic of color worked for me.

On to my first 5 tattoos, and they are permanent. In preparation for external beam radiation, my upper body was marked to ensure that every time the radiation beam would follow exactly the same path to my tumor, without damaging neighboring organs. Precision was ensured by tattooing tiny dots to pinpoint the entry points for the invisible radiation beams.

Next came the body mold, sometimes called a shell. It’s a lightweight mesh material, pliable when warmed. I lay on it, as 6 radiation therapists, 3 on each side, pull the mold material halfway up around my upper body. The mold hardens quickly, conforming to my curves, ensuring that I always lie in exactly the same position, so that the invisible radiation beams line up precisely with the tattoo dots, then zoom on to the target tumor.

I’m always safe and in the right place. Radiation therapy affects only the targeted tumor in contrast to chemotherapy that reaches the entire body.

Let’s get started.

The “Big Blue” Machine

“Big Blue,” my name for the huge radiation machine, has 3 moving parts—a round part above and 2 rectangular side panels. They circled around me like planets in orbit, but never touched me. One by one, the panels moved into position over and beside me, then buzzed a few times. It was painless. I felt nothing. Rectangles came first. Buzzzzz. The round one last, a signal that today’s treatment was almost over. All this took 10 to 15 minutes. I lay safely cradled in my mold. Some days I tried to imagine my tumor being zapped.

I was alone in the treatment room. Nurses close by monitored me and Big Blue. We talked back and forth. Oncologists, nurses, radiation therapists, reassuring, confident, fighting for me, ready to help. I looked forward to our few minutes of conversation about the weather, family, schedules, sports, my progress.

Nevertheless, toward the end of my radiation treatment, I began to feel angry and questioned the whole setup. What if this is one big con job, teasing, tricking, testing me? Note to self: get a grip. You’re just not that important.

With every passing treatment, I grew weaker and more exhausted. Fortunately, parking for patients coming in for radiation was just in front of the hospital. Fingers crossed for an open space.

One morning, the area was blocked off. Trucks, cameras, spotlights, wires, people in dark blue clothes. Shooting scenes for the TV show “Chicago Fire,” one of my favorites. Complimentary valet parking for patients coming for radiation, and an apology coupon for treats at Bon Pain from the hospital president.

Express Train

Radiation therapy has a life of its own. I wanted to yell—“slow down, give me a minute to catch my breath. How about we reconsider this whole thing?” It felt like an express train, no exit till the last stop. And you can’t slow it down—appointments, schedules, papers, instructions, medications, getting ready, driving, parking, finding a seat in the waiting room where CNN blasts Washington news or lack thereof, any new coupons for Ensure? (Yes), Boost? (No), waiting, wondering about other patients, changing clothes, weighing in, meeting Big Blue, dressing, checking out, reviewing the progress with staff, heading to the cafeteria for ice cream, driving home, resting. The whole day was gone, multiplied by 28 days, weekends off.

My Tumor Is Dying

The radiation therapy worked. It began to hurt, really hurt. The pain medications helped. Part of me is being systematically and deliberately killed. My tumor is dying. It’s painful, and it’s not giving up without a fight.

I felt fortunate and was enormously grateful. A follow-up PET scan showed no evidence of any remaining cancer. Now rest for 2 weeks, then proceed to surgery, which is called an esophagectomy.

Seven Years Later

No one told me that esophageal cancer is often fatal (if diagnosed at a late stage). A friend and retired oncologist advised that I not look it up online. I didn’t.

Even in my darkest moments, I accepted cancer as a part of me, and never doubted that if I did what they asked of me, I would recover—maybe not quickly, but in good time. Not knowing freed me to believe, be positive, and grateful. Seven years later, here I am.