Palliative care means taking care of people with chronic illnesses focusing on their quality of life, relief of pain and suffering, and supporting their families. This is so important, because people with chronic illnesses, such as cancer, are often living for years and decades, according to Diane E. Meier, MD, a leader in palliative care who was an agent of change, applying palliative care not only to people who are dying but also to people living with a chronic, possibly terminal illness.

A Palliative Care Nurse

As a palliative care nurse, I help relieve pain and suffering for patients with cancer and their families. My role is to relieve pain and suffering for patients with chronic cancer-related pain, which could last for many years. I also assist my patients if they need to transition to hospice care. I consider myself a skilled palliative care nurse, but I am always learning more from my colleagues and my patients’ families.

Still, I was not prepared for coping with being a daughter and a palliative care nurse when my mom was dying. Her death gave me an inside look into the families I help to comfort during a patient’s end of life—the families I help to relieve their suffering and facilitate necessary conversations. This story about my mom is not all roses and butterflies; some of it is hard to hear: not every death is alike.

My Parents

My mom died exactly the way she wanted to die; she never spoke of it, she did not give us unforgettable advice before her death, and she never sat down and said, “I love you.” This was hard for me, because this is exactly where my skills are. But after she died, there were so many “I love yous”—too many to count.

My mom had been sick for years; she had an open-heart surgery 12 years ago. She quit smoking, which was hard; she loved to smoke. With time, her congestive heart failure, COPD, and damaged lungs continued to decline. But it was only in the last couple of years and after many hospitalizations that she or my dad could no longer conceal her declining health.

My dad is the picture of health, that 84-year-old man riding his bike in 32-degree weather, going to the gym every day, and encouraging health and fitness for everyone he meets. But his mind is frail, his memory and comprehension are tenuous at times. My dad was able to compensate for my mom’s physical decline, and she, for my dad’s mental weakening. Together they were one whole person; separately they struggled.

COVID-19 & Quarantine

In late October 2020, my mom got COVID-19, and we were certain that this was the end. She was admitted to the hospital for a week, we could not see her, and she would call us, “Get me out of here; please let me come home.” On day 5, she called with a hoarse-sounding voice and shortness of breath, saying: “I am coming home.”

At first, we wondered why they were discharging her, then it hit me like a freight train: “Get her out of there!” If we don’t, she would die there alone, and we would see her via a screen on a hospital-supplied iPad.

Nursing at Home

Of the 7 siblings in our family, 3 are nurses, so we understood the COVID-19 reality, and if our mom was going to decline, it was going to be at home. At home, it was 30 days of quarantine. All 7 children jumped in to assist with our parents. Imagine the blue and yellow gowns, gloves, masks, and face shields every time you went to see your parents for hours.

I would leave work in a mask to go home in a mask. Preparing meals and educating, “You cannot share food, or drink; don’t eat off the same big platter; every time you touch something, I have to clean it.” This was difficult—we are a big, close family, “what is yours is mine” type of family.

Then there was trying to explain to my dad, “Mom was positive for COVID-19, and you have to be quarantined as well.” You know where I am going with this, right? So, when he did go out, and yes, he went out, he had on 2 masks, a face shield, and gloves. I am surprised he was not arrested as a bank robbery suspect.

My mom did well and was recovering from COVID-19, getting her strength back, and then, boom, like a ton of bricks, she was sick again. This was not surprising: in 2019 she had been hospitalized 6 times, but this time was different, and she was different. With high fevers and unable to breathe, she had to go back to the hospital.

She said, “No, I will not go back to the hospital.” My sister and my dad looked at me and said, “You do this for a living, what do we do now?” It was time for me to put on my end-of-life hat with my own family.

My mom and I had talked about end of life and hospice before, but not to the full extent. I found out that her main goal was to stay home and not go back to the hospital, no matter what, even though we never discussed the “no matter what.” She already had home health, so the transition to hospice care at home was seamless, in theory.

Over the next 2 months in hospice, my mom showed signs of improvement; she was eating better, going to the store with much support, she was talking on the phone, telling her family and friends that hospice was for the living.

She knew what I did for a living, but she would ask several times a week if I thought she was dying. I always said, “Mom, you are not dying imminently; you are very sick, and things can change fast. That is why hospice is here to help us. Is your wish still not to go to the hospital?” She quickly said “No,” with that extra word, big eyes, and head shaking from side to side.

Terminal Restlessness

Despite all my training, education, and experience, the 2 weeks before she died did not prepare me for my own mom’s dying process. She had what is called “terminal restlessness, with existential suffering,” which is when the physical body does not match up with the soul. My mom was not ready to die; her soul wanted more out of life.

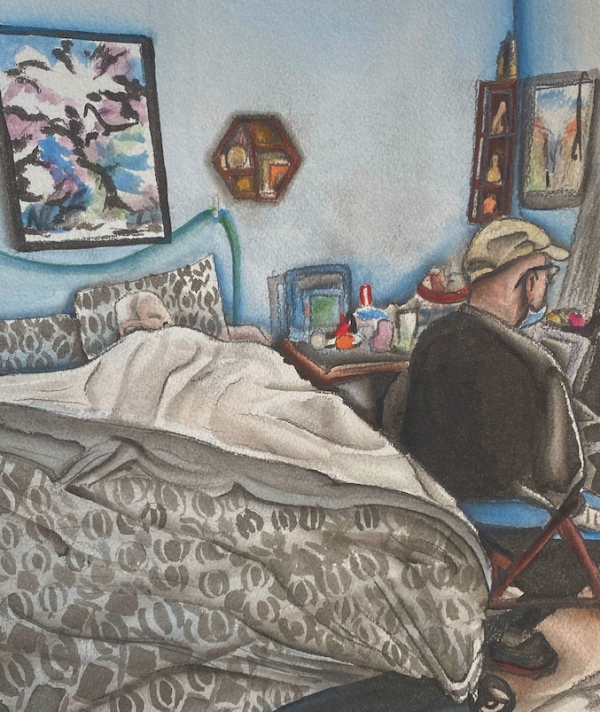

During her phase of terminal restlessness, she would be asleep for hours, then wake up full of energy, so much so that she could never be left alone, and my dad could not be her caretaker anymore. She was hiding things, such as cookie dough or medications, in the closet, reorganizing her drawers, or doing laps around the living room with her walker—with no oxygen. She was an adult toddler.

You may think that it must have been terrible to experience, but in fact it was not. My mom never spoke of dying, she never told us goodbye, but she did let us bathe and dress her, cook for her and feed her, sit in bed with her and cuddle, things that she did for all of us. She was finally allowing us to take care of her.

It was Christmas, which was her absolute favorite time of the year. When decorating this season, she sat in a chair, pointed at where she wanted stuff, and her grandchildren put it in place. I took her to the store to buy presents for the neighbors and kids. She was a bit confused and stubborn, but this was important to her, and I knew the time was very short.

As she got sicker, she couldn’t get out of bed and needed more medications to help her breathe and relax. Hospice care was coming over daily now: 2 days before Christmas was the last time she would be awake. That day, the hospice nurse whispered in my mom’s ear, “Peg, you are dying, please let your family take care of you.” My mom passed 2 days later, at 11:11 PM Christmas night, with a lot of family by her side.

After her death came the realization of my mom’s love for all of us, in good times and bad times. She kept everything—from the hospital gazette in which she was featured before she married my dad, to the cards we gave her last year, to her pearls from her wedding and the letter my dad wrote her on their 14th wedding anniversary. She kept all this to tell us she loved us, and that she could not always show her appreciation, but it all meant so much to her.

Caring for a Dying Person Is an Art

Everyone’s dying story is different. I now know what it takes to work full time, raise a family, and help a loved one die. Palliative care is my trade, my profession. Caring for a dying person is an art. An art of love, exhaustion, understanding, regrets, happy and sad emotions all bottled up in one main theme.

It takes a village to help someone die. It is not easy, but because of this, my mom has made me a better person and a better nurse. For that I have no regrets.