Supported by

Thank you for taking the time to read about cholangiocarcinoma and the pathways involved in your cholangiocarcinoma care. The following discussion will take you through the testing and treatments you are likely to encounter and discuss with your healthcare team, cover strategies to help you take the best care of you, and provide resources to support you on your path forward.

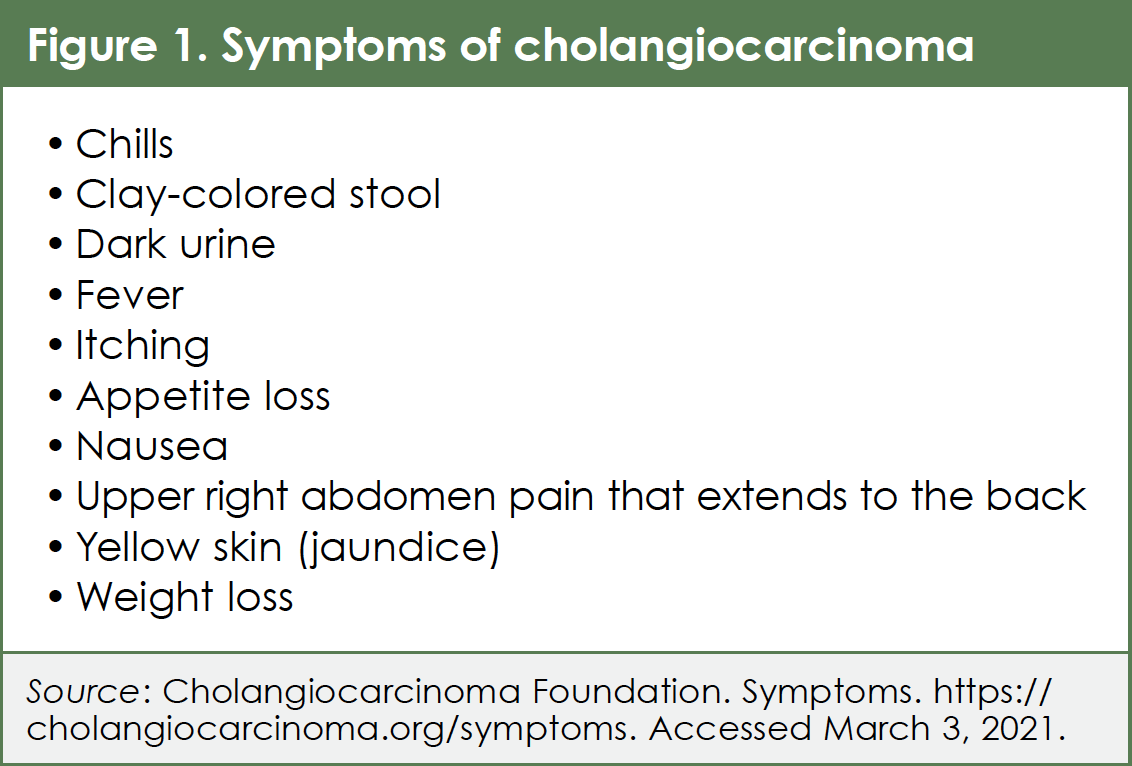

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a cancer of the bile duct. Most often, symptoms of CCA are noticed late in the disease process and therefore lead to a late diagnosis.1 The symptoms shown in Figure 1 may be associated with CCA and should all merit a work-up to include causes of bile duct obstruction and/or CCA.1,2

Cholangiocarcinoma is relatively rare in the US, with approximately 8000 new diagnoses occurring each year. However, the number of diagnosed cases of intrahepatic CCA (CCA within the bile ducts in the liver) is increasing.3 People who have a history of prior bile duct disease or inflammation are at increased risk of developing CCA. A history of cirrhosis, swelling of the part of the bile duct outside the liver (choledochal cyst), exposure to certain chemicals (eg, nitrosamines polychlorinated biphenyls [PCBs]), and older age can increase the risk of developing CCA.4

Anatomy

CCA refers to a type of cancer (carcinoma) of the cholangiocytes, which are the cells that line the inside of the bile duct.5 When these cells grow abnormally, they can form a tumor that grows into the bile duct, blocking the flow of bile into the small intestine.6,7 Most cholangiocarcinomas are a type of adenocarcinoma, which is cancer that develops in fluid-secreting cells (in this case, the cells that secrete bile).

Cholangiocarcinoma can form inside the bile ducts within the liver (intrahepatic CCA) or in the larger ducts outside of the liver (extrahepatic CCA) (Figure 2).8 Although the smaller ducts are inside the liver, intrahepatic CCA is not considered liver cancer. Another location where CCA may form is where the left and right hepatic ducts meet. CCA in this location is referred to as hilar CCA or can also be known as a Klatskin’s tumor.7 There can be 1 or multiple tumors in the bile ducts.9

Evaluating Your Cancer

Initial testing

There are a variety of tests that may be performed to tell your healthcare team more about your overall health, how well your kidneys and liver are working, specific characteristics of your tumor, and other information that can help guide treatment planning and other decisions (Table 1).10,11 This section will provide information about several types of tests.

Your doctor may have ordered blood tests such as liver function tests and imaging studies to help support a diagnosis of CCA.10,11

Blood tests might include:

- Comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP): Evaluates kidney function and electrolytes in your blood

- Liver function tests: Examines liver enzyme levels and bilirubin (increased levels of bilirubin can indicate that there is a blockage of the bile duct)

Depending on whether intrahepatic or extrahepatic CCA is suspected, additional tests may be selected:

- IgG4: To rule out autoimmune cholangitis.10-12

- Hepatitis panel: To detect exposure to the hepatitis B virus13

Imaging

Imaging can help to determine:

- The exact location of the cancer

- Whether it is liver cancer, CCA, or has spread to the liver from other organs (metastases)

- Where the CCA is located in the bile ducts

- If the CCA is inside or outside the liver (intrahepatic or extrahepatic)

Imaging may be performed throughout the diagnostic process, during your treatment, and to monitor your health after treatment is complete.

Imaging methods for examining cancer include computed tomography (CT), which is a series of x-rays taken of body sections, and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which uses magnetic fields (not x-rays). For detailed images of specific areas or organs within the abdominal cavity, imaging techniques might be combined.11 Imaging may also evaluate whether the cancer has spread (metastasized) to other body regions.

Another type of test called an endoscopy uses a tube-shaped instrument (an endoscope) with a camera and light, used to view inside the gastrointestinal tract (including inside the biliary ducts).14

Biopsy

A biopsy may be ordered, which is a sample of the tumor taken for evaluation by a pathologist. Collection of an adequate tumor sample is important to allow for extensive testing. The sample may be collected using an endoscope or can involve other imaging to help guide a thin needle through the skin and into the abdomen to collect cells from the tumor.10 A multidisciplinary team will determine the need for a biopsy and will determine the best procedure to obtain it.

This pre-biopsy consultation may also help to determine if a biopsy would be helpful in treatment selection.13

Tumor marker testing

Like imaging, other tests may be performed early in the course of your care to help guide the best treatment options for you.

Blood biomarker tests detect proteins associated with cancer:

- Cancer antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9)

- Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

- Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP; more rarely)

However, the proteins detected by these tests are not always elevated in CCA patients, and other diseases can also produce elevated levels of these proteins. For this reason, these tests are not used for diagnosis, but they may help provide additional information.10

Biomarker testing

Tumor biomarker testing searches for genetic mutations or abnormalities that can occur in some individuals with CCA. Certain treatments have been found to be more effective in patients with specific gene alterations.15,16 The Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation (CCF) website has a helpful animated video, “Mutations Matter,” about why a biomarker test is ordered, the kind of information it provides, and its relevance to your treatment selection: https://cholangiocarcinoma.org/mutationsmatter.

One format of mutation testing is referred to as next generation sequencing (NGS), which is less costly and requires about 10 to 14 days for results.16 Panels of different tumor mutations have been created for NGS. To evaluate genetic alterations that could be targeted by various therapies, a multigene NGS panel of tests should be selected for patients with CCA.16,17

In fact, it is becoming increasingly more important to carry out biomarker testing in managing CCA as a new generation of precision medicine drugs are being developed that work only in cancers that have a specific genetic biomarker profile.18,19

Shared Decision-Making

Questions to ask about testing:

- What tests are recommended for me and will you include biomarker testing?

- How long until we know the test results?

- How will the test results affect my treatment?

- How will my comfort be managed during the testing procedures?

Stage of your cancer

Testing following your initial diagnosis can help to stage the cancer based on tumor size (T), the involvement of nearby lymph nodes (N), and whether the cancer has metastasized to distant organs (M). For this reason, this method of staging cancer is known as the TNM classification system.20,21

The TNM system is based on 3 key pieces of information:

- The extent (size) of the main tumor (T): How large has the cancer grown? Has the cancer reached nearby structures or organs?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or distant organs such as the bones, lungs, or peritoneum (the lining of the abdomen)?

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced.21

Other terms may also be used in describing the stage of cancer, such as local, locally advanced, metastatic, and recurrent. Local cancer occurs within the bile duct and can be surgically removed. Locally advanced cancer occurs around the bile duct and affects adjacent organs or blood vessels. Metastatic cancer has spread to another body locations. Recurrent cancer has returned after treatment.20 Staging the cancer can help direct an appropriate treatment selection.21 For more details about staging, see The National Cancer Institute’s review of treatments and staging in Bile Duct Cancer (Cholangiocarcinoma) Treatment (PDQ)—Patient Version.11

Consulting a specialist

Another important component of the evaluation process is receiving input or guidance from a surgeon and an oncologist who specialize in treating CCA. The medical oncologist will drive your care and a surgeon will be involved if the cancer is operable or if a surgical problem arises where surgery is necessary. If you are unsure of where to find a specialist, the CCF website has a resource for locating a specialist in your region or for setting up a virtual call with the specialist: https://cholangiocarcinoma.org/newly-dx.15 On this website, you will also find a free helpful resource, Ciitizen, for managing your medical records in preparation for visits, for keeping track of the tests that have already been performed, and even for finding clinical trials in CCA.15 Specialist input may be provided as part of a multidisciplinary team, which might include a surgical oncologist (or surgeon), radiation oncologist, medical oncologist, gastroenterologist, and liver specialist (hepatologist).22 You may also be seen by an interventional radiologist, a specialist who uses imaging to perform less-invasive procedures that diagnose or treat diseases. For example, an interventional radiologist may collect biopsy samples. If a multidisciplinary team is not available, you may be referred to individual specialists.23

Several healthcare sites list questions that you may want to ask your healthcare team:

Shared decision-making

Throughout your care pathway, you and your healthcare team together will review test results, information about your diagnosis, health history, personal preferences, and your treatment options to make informed and collective decisions regarding your health.24 This collaborative approach to your care is referred to as shared decision-making. This individualized approach to making healthcare decisions involves discussing your personal concerns and beliefs and how these might impact your decision-making process. Other concerns or questions that you have along the way about cost of treatment, concerns or fears about treatments and their side effects, your quality of life, your nutritional habits, and even your favorite activities and life goals can help shape the treatment to best suit your needs.24 In preparing for conversations with your healthcare team, it may be helpful to write down your questions and concerns as they occur to you. It may also help to review available lists of questions that may not have occurred to you to ask.

Shared Decision-Making

Tell your healthcare team about your preferences:

- Your personal beliefs

- Your concerns

- Your favorite activities

- Your lifestyle

Treatment

There are a variety of approaches to treating CCA, depending upon its location, stage, your general health status, and your individual needs. These might include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, locoregional therapy, immunotherapy or targeted therapy, a combination of these (chemoradiation, for example), or enrollment in a clinical trial. The selection of treatment generally follows from whether the CCA is surgically removable (Table 2).11,22,24

Surgery

The complete surgical removal of CCA is the only potential cure for patients with resectable disease, and a multidisciplinary, or multi-specialist, approach is needed in considering whether the tumor(s) can be removed with surgery.13 If surgery is considered, a therapy may be started before surgery that can reduce the tumor size so that it can be surgically removed. Therapy in this instance is referred to as neoadjuvant therapy. Therapy following surgery, called adjuvant therapy, may also be recommended.25

Surgery may involve the partial or entire removal of the bile duct, and/or part of the liver, and should also include lymph node removal.24 For some patients with hilar CCA outside the liver that cannot be removed with surgery, a liver transplant may be a consideration.11

Before surgery, as part of informed consent, you will be provided with information about the surgery, risks associated with surgery, and additional tests that may be ordered to evaluate your health prior to the surgery.26 You should also be provided with instructions about eating, drinking, and taking any medications before your surgery. Anesthesia for surgery may be delivered in different ways with differing effects. The American Cancer Society has a helpful list of descriptions of the different types of anesthesia: www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/treatment-types/surgery/recovering-from-cancer-surgery.html. The expected course of your recovery from surgery should also be discussed, including any recommended diet, activity level, wound care, and medication instructions.26

Therapy given after surgery, referred to as adjuvant therapy, will likely be recommended, even when the tumor(s) appears to have been completely removed.24 Adjuvant therapy may include any of the therapy types that targets the whole body, known as systemic therapies (the descriptions of which follow). Currently, capecitabine is recommended for 6 months as an adjuvant therapy after the complete surgical removal of CCA.24,27 Alternatively, either monitoring or a clinical trial may be recommended by your doctor(s). If a microscopic amount of cancer is detected in the surrounding lymph nodes following surgery, additional therapy may be recommended.24,27

After surgery and subsequent therapy are completed, your healthcare team will recommend routine monitoring or surveillance for the possible return (recurrence) of the cancer. Routine imaging every 3 to 6 months with CT or MRI are typically recommended for the first 2 years after the end of treatment, and then at 6 to 12-month intervals for as long as 5 years. Your healthcare team will review a plan for surveillance with you.28

Shared Decision-Making

Questions to ask about surgery:

- What are the risks of this surgery?

- Will all or part of the cancer be removed?

- What will be the length of my hospital stay?

- What are my anesthetic risks?

- What would happen without the surgery?

- Will my tumor be molecularly tested?

Clinical trials

Enrollment in a clinical trial may also be considered. Several clinical trials that are currently enrolling patients are listed on the CCF website: https://cholangiocarcinoma.org/professionals/research/clinical-trials. There is another website available, www.clinicaltrials.gov, which is a global database of clinical trials. To be considered for a clinical trial, a patient has to meet that trial’s specific eligibility criteria. These might require certain characteristics of a medical history, whether they have had prior treatment for CCA, and the stage and/or location of the disease. Some of the ongoing trials study how well patients who have tumors with certain genetic abnormalities respond to therapies that target those abnormalities or how the tumors respond to immunotherapy. For example, 1 trial found that patients with a genetic abnormality known as an FGFR rearrangement responded to a drug that blocks FGFR, pemigatinib.29 Another such trial found that CCA with IDH1 mutations responded to a therapy that targets IDH1, ivosidenib.30 Discuss whether a clinical trial might be an appropriate consideration for you with your healthcare team.31

Clinical trial resources:

- CCF clinical trial webpage

https://cholangiocarcinoma.org/professionals/research/clinical-trials - Clinicaltrials.gov

https://clinicaltrials.gov

Shared Decision-Making

Questions about clinical trials:

- Is a clinical trial appropriate for me?

- What are the potential benefits of a clinical trial for me?

- Would I meet a clinical trial’s eligibility requirements?

- Why is a clinical trial being recommended for me?

- How will safety be ensured during a clinical trial?

- Would I be able to discontinue the trial if I choose to?

- Will my insurance cover clinical trial treatment?

Systemic therapies

Chemotherapy. When the disease is determined not to be removable by surgery or has spread to other parts of the body (metastasized), systemic therapies, or therapies that treat the entire body, may be considered.24 Systemic treatment regimens include chemotherapy that may be used alone or may be combined with other systemic therapies. Also, therapies known as targeted or immunotherapies are systemic drugs that target or block specific molecules that support the cancer’s growth and maintenance. These types of therapies are often available primarily through clinical trials. If the cancer has metastasized, depending upon the extent of metastasis and your general health condition, clinical trial enrollment or palliative treatment (treatment only of symptoms) may be appropriate considerations.24

Chemotherapy has been shown to extend survival times in patients whose cancer could not be surgically removed.24 A chemotherapy regimen may be recommended that usually includes the drugs gemcitabine and cisplatin, alone or in combination with other chemotherapeutic drugs.24 Other combinations include 5-FU with oxaliplatin or cisplatin, capecitabine with cisplatin or oxaliplatin, gemcitabine with capecitabine, or oxaliplatin or cisplatin and albumin-bound paclitaxel. The therapies 5-FU, capecitabine, and gemcitabine may be prescribed alone. There may be different cycles, or repeating dose schedules, for the chemotherapy (these are usually 2 to 6 weeks in length).24

Depending on the regimen, the side effects of chemotherapy can include increased infection risk, nausea and vomiting, appetite loss, hair loss, and diarrhea. Most of these effects subside after the end of the treatment but can continue, or may even not occur, until after the end of the treatment. The severity of these side effects is different from 1 patient to another.32

Side effects that affect your appetite and level of comfort can also impact your overall health and the effectiveness of your treatment. For example, if the side effects are severe, your healthcare team may determine that the dose(s) of your treatment need to be decreased or the treatment disrupted or discontinued. Therefore, during and after chemotherapy it is important to maintain ongoing communication with your healthcare team about any side effects that you are experiencing.32 Recording your side effects in a journal, or even using available digital programs like the Cancer.Net mobile app (available here: www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/managing-your-care/cancernet-mobile) can help your healthcare team decide whether any adjustments to your regimen should be made.32

Targeted therapy. This form of therapy is selected to treat disease with a known genetic mutation or alteration that is detectable through tumor biomarker testing. These genetic changes in the tumor have occurred over time or are acquired and are not passed to children from parents.33 For example,

- Pemigatinib has been approved by the FDA to treat CCA that has a genomic alteration called FGFR2 fusion and where the tumor has progressed after treatment with chemotherapy.

- There are also targeted agents that are not FDA-approved yet but are in late stages of clinical development for CCA that progressed on chemotherapy.

- Infigratinib has shown promising activity against tumors with the FGFR2 fusion genetic abnormality in a clinical trial.34-36

- Futibatinib, also has shown promise in patients with FGFR2 fusions or rearrangements.37

- Ivosidenib has been shown to be safe and effective in patients with an IDH1 mutation.38

- There are a several other genetic alterations that are being studied as potential targets in treating CCA, including mutations in BRAF, HER2, NTRK, and VEGF.18 The results of these ongoing clinical studies may expand the number of targeted agents that are available in providing personalized therapy for CCA.

- Immunotherapy may also be effective in certain patients with CCA whose tumors have progressed on chemotherapy. Investigations into specific genetic alterations that may make immunotherapy more effective are also ongoing, including PD-L1, MSI-H, and dMMR.18

It is important for you to discuss molecular biomarker testing with your healthcare team as soon as the diagnosis of CCA is made to help you navigate through all these genetic alterations. It appears that nearly half of patients with CCA have some genetic alteration that may be a specific target for therapy.19 This makes biomarker testing increasingly more important to clinical practice as a new generation of precision medicine drugs that target these genetic alterations become available or are in clinical research.

Some common side effects of these targeted agents include gastrointestinal upset, constipation, too much or not enough phosphate in the bloodstream, fatigue, a dry or sore mouth, nail changes, and back pain.39 These side effects vary depending on the therapy and your body’s response to the therapy. It is important to discuss your concerns about these side effects and what you need to do if you are experiencing them with your healthcare team.

Immunotherapies increase the immune system’s response to cancer. A small percentage of patients with CCA may respond to the immunotherapies like pembrolizumab or nivolumab. Side effects with these agents include flu-like symptoms, skin reactions, diarrhea, and weight change.24,40

Resources that list the possible side effects of various drugs:

Local therapies

Another type of therapy known as locoregional therapy may be considered for unresectable or metastatic intrahepatic CCA.13 This type of therapy requires the expertise of a radiologist who specializes in this type of treatment (called an interventional radiologist). Locoregional therapies (therapies that are delivered to a specific organ or part of an organ) may be used to freeze or heat cancer cells. Another type of locoregional therapy involves photodynamic therapy (PDT), in which administration of a light-reactive drug is followed (after a few days) by introduction of a red light that is focused on the tumor, causes cancer cell death.23 Yet another type of locoregional therapy, trans-arterial chemoembolization, or TACE, delivers chemotherapy directly to the cancer using imaging as a guide and blocks the blood supply to the tumor using blood vessel-blocking agents.23

Radiation therapy is another form of local therapy that can be used to treat the cancer or to provide palliative care that alleviates symptoms of the disease. Radiation entails high-energy x-ray beams that kill cancer cells.24 For CCA that is considered unresectable or where some of the disease remains after surgery, radiation combined with chemotherapy (chemoradiation) may be recommended—for example, external beam radiation combined with chemotherapy.24

Less commonly used forms of radiation are administered internally with radiation-emitting implants that directly target the cancer (brachytherapy) or with radiation-emitting beads placed in the blood vessels supplying the tumor (radioembolization). There can be skin and gastrointestinal side effects in addition to fatigue resulting from radiation therapy. These side effects can affect your appetite and level of comfort. Discuss how you are feeling with your healthcare team routinely and track these side effects. For some tips on managing common side effects associated with radiation therapy, see the discussion on self-care.24

Shared Decision-Making

Questions to ask about therapy:

- What are the best treatment options for me?

- Which treatment(s) do you recommend?

- How long will the treatment last?

- How will this treatment affect my life?

- How can I stay healthy during treatment?

- What are common side effects of these treatments and how will I be able to manage them?

Monitoring

Regardless of the type of treatment that you select with your healthcare team, your response to the therapy will require monitoring. Monitoring often entails laboratory tests and imaging with a schedule that is determined by the type of therapy and the point in time in your therapy. During public health crises like COVID-19, some of this monitoring can be performed at clinics that are off-site from the main hospital (and that may be closer to you), and discussions with your healthcare providers may be conducted via telemedicine.41

Treatment and monitoring safety during COVID-19

- Call your healthcare provider before visits for guidance on safety procedures followed at their facility

- Ask about off-site or alternative clinics to decrease potential exposure risk

- Some routine appointments or follow-up visits may be conducted via telemedicine

- You may be able to have certain oral prescription medications directly delivered to you41

Progression of the cancer

If the cancer grows or progresses during or after your treatment, you will need what is called second-line therapy. This may involve a combination chemotherapy regimen known as FOLFOX (or sometimes FOLFIRI). However, if your tumor was positive for certain molecular changes that might respond to a targeted therapy, then this may be considered. Clinical trials are always a consideration along the cancer care continuum as well.24,42

Life during and after treatment

Now that some of the basic steps in your diagnosis and treatment have been reviewed, a discussion is warranted on how that medical path intersects with your body and your life. A large part of this is taking care of yourself (self-care) by managing symptoms, communicating with your healthcare team, and getting appropriate support for your physical and mental well-being.

Palliative/supportive care

Palliative care refers to the treatment of symptoms, which can take place during curative treatment and enhance quality of life. Palliative care can begin at the time of a disease diagnosis.43 In fact, it is recommended that palliative care be initiated soon after the diagnosis. Patients who receive palliative care throughout their cancer treatment have been shown to have a better quality of life with fewer symptoms and have more satisfaction with their therapy.24 Palliative care includes the prevention and relief of cancer treatment-related side effects and can occur in a variety of settings (ie, hospitals, clinics, home).44 Medicare, Medicaid, the Department of Veterans Affairs (for veterans), and private insurers may provide coverage for palliative care. Check with your health insurance provider for details on palliative care coverage.43

Palliative care consultation teams coordinate with the patient, patient’s care partners, family, and doctors for medical, emotional, social, and other types of support.43 Such teams may include doctors who specialize in palliative care, nutritionists, nurses, and social workers.43

Hospice care differs from palliative care in that it involves the treatment of symptoms, or supportive care, for a patient who is not on active cancer treatment. This includes patients with a terminal illness and for whom doctors do not expect survival beyond 6 months.43

Seeking a palliative care team early is recommended. There are several patient palliative care resources:

- National Hospice and Palliative Care

Organization: CaringInfo

www.nhpco.org/patients-and-caregivers - The Center to Advance Palliative Care

www.getpalliativecare.org41

Survivorship

Survivorship refers to a combination of medicine and self-care to prevent the return of cancer and/or to prevent a new cancer from forming. This can involve treating side effects of therapy or screening for new cancer during a monitoring period. Another part of survivorship involves a focus on health maintenance and promoting maximized quality of life through self-care.45,46

Practicing self-care

During treatment, making healthy choices can improve your quality of life. After treatment, taking steps to improve your health can reduce the chances of cancer recurrence.47 Your healthcare team can help to provide or find support (ie, a counselor, registered dietician, and/or a physical therapist) for you as you take steps to become healthier. Before, during, and after treatment, taking care of yourself is an important part of your health and wellbeing. Caring for your health and overall wellbeing encompasses managing your nutrition, symptoms, and overall physical, emotional, and mental health. For added support, CCF has recently launched a Wellness for Life initiative, which you can find out more about at: www.facebook.com/CCFW4L.

Nutrition

Nutrition is an important factor in CCA treatment and management, particularly in terms of maintaining lean body mass, which also involves exercise. Avoidance of malnutrition can be a challenge for patients with CCA for the following reasons:

- Digestion difficulties.48

- Special diets recommended for some patients (for example, low-phosphate diet recommended for those treated with pemigatinib).49

- Treatment-related nausea

Strategies for improving your nutrition include:

- Look into some of the several cookbooks available for patients with cancer.

- The ACS has a cookbook, What to Eat During Cancer Treatment50

- Devise a personalized nutrition plan that incorporates your food preferences and dietary needs with the help of a registered dietician.51

- Find a nutritionist with training in oncology: www.eatright.org/find-an-expert

One of the more common challenges for patients with cancer is eating. Nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea, and a sore mouth can make eating and weight maintenance difficult.52 These symptoms can result from the cancer therapy or the cancer itself. Nausea, the feeling of being about to vomit or of being sick to your stomach, is often described by patients as being worse than the vomiting itself. Preventing nausea is critical because nausea is difficult to control once it begins. Vomiting, also referred to as emesis, is the emptying of the stomach’s contents and can result in the loss of fluids and important minerals that your body needs. Thus, your healthcare team may provide you with medication to prevent nausea prior to starting a cancer therapy. Reviewing any history you may have of nausea and vomiting will also help your healthcare team to plan and prevent nausea and vomiting. However, you will need to continue to communicate your symptoms with your healthcare team to enable management of nausea and vomiting.53,54

- There are many strategies to help you with nausea, difficulty eating, and loss of appetite. For example, high calorie drinks can support weight maintenance and hydration if your appetite for solid foods is poor or your mouth is sore.45,55 You might also consider eating multiple small meals throughout the day and having puddings, soups, or yoghurt for snacks. If you are nauseated, try bland foods (eg, crackers or toast) and avoid fried, fatty, and aromatic foods.55 You may also want to avoid cooking food when you are nauseated. You might find that seasoning your food enhances its appeal.45 Discuss your appetite with your healthcare team—there are anti-nausea (antiemetic) medications that can help. If you have been prescribed antiemetic medication(s), continue to speak to your healthcare team about any nausea you still experience. Again, seeking consultation with a nutritionist may help you tailor a strategy to maintain lean body mass and energy while taking into consideration your symptoms.54 Some patients have found that alternative therapies such as ginger or peppermint teas have been helpful in alleviating nausea.55

Components of a healthy lifestyle:

- Healthy eating

- Physical activity

- Tobacco product avoidance

- Limiting alcohol consumption

Physical activity

Like healthy eating habits, physical activity can improve your quality of life and may even prevent some cancers from returning.

Physical activity can:

- Improve your mood

- Combat the fatigue related to cancer and its treatment

- Improve your cardiovascular health

- Improve your overall quality of life

The overall goal behind incorporating physical activity into your routine is to be active daily and to avoid long periods of inactivity. However, this can be a challenge for individuals with cancer and its treatment. Working with a physical therapist, occupational therapist, or other certified exercise professional—particularly if they are trained in cancer patient care—is recommended to personalize a regimen that considers your needs.56,57 Even taking short walks for 20 minutes per day for a few days per week is helpful.

It will also help your healthcare team to review patterns of your symptoms, which can be facilitated by a written log that you keep of symptoms (consider writing down your healthcare questions in the same location).

Pain management

Abdominal or back pain is common for individuals with CCA. It is important to speak to your healthcare team about pain management options, particularly if you are experiencing pain while at rest.58 Consider keeping notes about any pain you do experience, noting details like when the pain is occurring, what (if anything) helps to alleviate the pain, and how it feels (ie, a dull ache or sharp pain).58 The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has a free booklet on cancer-related pain management: www.cancer.net/sites/cancer.net/files/managing_pain_booklet.pdf

Pain with fever, chills, jaundice, and right upper abdominal pain could be symptoms of cholangitis, or inflammation of the bile duct, which can indicate an infection that requires immediate treatment (eg, antibiotics), because it can progress to life-threatening septic shock.59

Fatigue

Fatigue is another common experience of individuals with CCA and other cancers and can be therapy-related. Your healthcare team may be able to provide treatments for fatigue, so discuss this symptom with them if you are experiencing it. Some activity may help to counteract the fatigue and a physical therapist and/or personal trainer may be able to provide appropriate activities to support your energy level.60 Mindfulness practices like yoga, meditation, and massage, can also help reduce fatigue and nausea.61 In addition, an occupational therapist can work with you to develop strategies that help you conserve your energy throughout your daily routine.62

You can download a symptom-tracking application that helps you to track your symptoms and questions here:

Emotional wellness

Feelings of anxiety, stress, fear, and depression are normal for individuals with cancer. There are a variety of distress causes: your symptoms, treatment effects, financial concerns, access to healthcare, personal relationships, and your mental health status.63 A survey of individuals with CCA found that 38% were experiencing moderate depression while 47% had severe depression.64 Managing and expressing these emotions can also present a difficult hurdle (and another source of distress) for many patients. Distress can affect how patients diagnosed with cancer make decisions about their treatments and can result in worsening health. Hence, treating depression is considered an important part of cancer therapy.65,66 Speaking with a counselor or support group can help you to navigate these emotions. Additionally, ASCO recommends depression screening at the time of a cancer diagnosis and before and after cancer treatment.66 Screening for distress commonly involves some type of questionnaire or may have you rank your symptoms and/or concerns on a scale. Your healthcare team or doctor will discuss the results of the screening with you and use it to select the support that you need. You may be referred to a social worker, psychologist, psychiatrist, nurse, or chaplain, depending upon your needs.65 There are counselors who specialize in cancer and terminal illnesses. An example of these specialized counselors are oncology social workers (OSW-C), who provide support to patients with cancer. Some resources to help you find an oncology social worker are:

- Alliance for Quality Psychosocial Cancer Care: www.cancersupportcommunity.org/alliance-quality-psychosocial-cancer-care

- American Psychosocial Oncology Society: (866) 276-7443; https://apos-society.org

- Association of Oncology Social Work: https://aosw.org/patients-caregivers/find-an-osw-near-me

Connecting with CCA-specific or other cancer patient support groups may provide social support and lessen feelings of isolation (even during a socially distanced pandemic). Organizations like CCF and ACS provide resources for finding a support group near you. You may even find that volunteering for a patient-oriented organization or becoming involved as an advocate for other patients provides a positive means of engaging with the changes in your life. There are opportunities to find a mentor and to become a mentor for other patients with CCA on CCF’s CholangioConnect webpage: https://cholangiocarcinoma.org/cholangioconnect. Mindfulness practices like breathing exercises, meditating, and yoga have been shown to help manage anxiety and symptoms for patients with cancer.67 Various mindfulness techniques have been studied: mindfulness-based cancer recovery, mindfulness-based art therapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.67 In addition to meditation practices, relaxation techniques such as music therapy, guided imagery, acupuncture, and acupressure can help to counteract nausea.68 You may find that social planning (beyond the context of a pandemic) can become complicated. Plans such as attending an event or eating out may change depending upon how you may be feeling. Understanding that plans change can help people to still make plans but accept plan adjustments when needed.69

In the context of dating or intimacy, hesitance is common for individuals with cancer and may be overcome by positive self-talk, social engagement (ie, joining a club or group, and talking about dating or sociability with others who have cancer). Concerns about disclosure about illness vary depending upon the person: you may feel more appropriate sharing earlier in the relationship or after some establishment of trust.70

Finances

Financial concerns commonly present another burden to individuals with cancer. Costs can range from transport to a treatment center, doctor appointments, treatments, and counseling.71 There are numerous financial advice or support resources available, with a few listed here:

- Cancer Financial Assistance Coalition (CFAC)

https://cancerfac.org - Cancer Care

(800) 813-4673; www.cancercare.org - Cancer Finances

https://cancerfinances.org

There are also federal programs that can provide assistance to persons with disabilities, the Social Security and Supplemental Security Income disability programs. The website for these programs provides guidance on program application: www.ssa.gov/disability72

Although planning for your future may be more complicated with CCA, it may also help you to be prepared, live in the present, and live with hope. While the statistics for CCA long-term survival can be discouraging and do provide a rationale for planning accordingly, it is also important to avoid focusing on the numbers. Pursuit of self-care and the activities that you like now and in the future may not only help you enjoy life, but may also improve your health outcome.73

Get connected

There are multiple resources, in addition to your healthcare team, to support you on your path forward. The CCF website has a page for newly diagnosed patients, forums in which to connect with other patients, support group listings for patients and caregivers, event listings (including an annual conference and fundraising events). Familiarizing yourself with these resources may help you navigate your pathway through CCA and provide you with additional support. There are multiple organizations with websites that include resources for patients in the different stages of disease and treatment. Here are a few of the major organizations:

- Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation

https://cholangiocarcinoma.org - American Cancer Society

www.cancer.org - Cancer.Net

www.cancer.net - National Institutes of Health/National

Cancer Institute

www.cancer.gov - National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®)

www.nccn.org

For patient support:

- Cancer Hope Network

www.cancerhopenetwork.org - Triage Cancer

https://triagecancer.org - Cancer Support Community

www.cancersupportcommunity.org

For caregiver support:

- Cancer Horizons

www.cancerhorizons.com/caregivers - Cholangiocarcinoma Caregivers

www.facebook.com/groups/170301816796010

Questions to ask your doctors/healthcare team:

- CancerNet: www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/questions-ask-health-care-team

- ACS: www.cancer.org/cancer/bile-duct-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/talking-with-your-doctor.html

- NHI/NCI: www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/questions

For self-care:

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics:

www.eatright.org - Find a nutritionist trained in oncology nutrition:

www.eatright.org/find-an-expert - Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation Patient advocates:

Melinda Bachini, Director of Advocacy:

(888) 936-6731, extension 8

Dawn Scott, Patient Advocate:

(888) 936-6731, extension 22

Literature for individuals with CCA:

- 100 Questions & Answers About Cholangiocarcinoma, Gallbladder and Bile Duct Cancers by Dr Ghassan Abou-Alfa & Dr Eileen M. O’Reilly (to request the free book): https://cholangiocarcinoma.org/publications

- ASCO guide on appetite loss www.cancer.net/sites/cancer.net/files/asco_answers_appetite_loss.pdf

- National Cancer Institute: Bile Duct Cancer (Cholangiocarcinoma) Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version: www.cancer.gov/types/liver/patient/bile-duct-treatment-pdq

For clinical trial information:

- CCF’s clinical trial webpage https://cholangiocarcinoma.org/professionals/research/clinical-trials

- Clinicaltrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov

References

- Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation. Symptoms. https://cholangiocarcinoma.org/symptoms. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- American Cancer Society. Signs and symptoms of bile duct cancer. www.cancer.org/cancer/bile-duct-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/signs-symptoms.html. Accessed March 4, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Bile duct cancer (Cholangiocarcinoma): statistics. www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/statistics. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma): risk factors and prevention. www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/risk-factors-and-prevention. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- Bai M, Fu W, Su G, et al. The role of extracellular vesicles in cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20:435.

- Cancer.Net. Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma): symptoms and signs. www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/symptoms-and-signs. Accessed April 20, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma): introduction. www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/introduction. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma): medical illustrations. www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/medical-illustrations. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- Global Liver Institute. Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA): staging for cholangiocarcinoma. www.globalliver.org/cholangiocarcinoma-cca. Accessed April 13, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma): diagnosis. www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/diagnosis. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- National Cancer Institute. Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma) treatment (PDQ)—patient version. Updated October 1, 2020. www.cancer.gov/types/liver/patient/bile-duct-treatment-pdq. Accessed December 1, 2020.

- Du S, Liu G, Cheng Xet al. Differential diagnosis of immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis from cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:501-505.

- Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Hepatobiliary Cancers. Version 2.2021 – April 16, 2021. © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2020. All rights reserved. Accessed April 23, 2021. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way.

- MayoClinic.org. Cholangiocarcinoma (bile duct cancer) diagnosis and treatment. www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cholangiocarcinoma/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20352413. Accessed January 14,2021.

- Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation. Newly diagnosed. https://cholangiocarcinoma.org/newly-dx. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Mosele F, Remon J, Mateo J, et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with metastatic cancers: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1491-1505.

- Cao J, Hu J, Liu S, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: genomic heterogeneity between eastern and western patients. JCO Precision Oncology. 2020;4:557-569.

- Sardar M, Shroff RT. Biliary cancer: gateway to comprehensive molecular profiling. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2021;19:27-34.

- Lowery MA, Ptashkin R, Jordan E, et al. Comprehensive molecular profiling of intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas: potential targets for intervention. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:4154-4164.

- Cancer.Net. Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma): stages. www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/stages. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- American Cancer Society. Early detection, diagnosis, and staging. www.cancer.org/cancer/bile-duct-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging.html. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- American Cancer Society. Treating bile duct cancer. www.cancer.org/cancer/bile-duct-cancer/treating.html. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation. Treatment options. https://cholangiocarcinoma.org/treatment-options. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma): types of treatment. www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/types-treatment. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Neoadjuvant therapy. www.cancer.net/neoadjuvant-therapy. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- American Cancer Society. Treatment and support: Getting ready for and recovering from cancer surgery. Updated October 2, 2019. www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/treatment-types/surgery/recovering-from-cancer-surgery.html. Accessed December 1, 2020.

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. Research guidelines: gastrointestinal cancer: adjuvant therapy for resected biliary tract cancer. www.asco.org/research-guidelines/quality-guidelines/guidelines/gastrointestinal-cancer#/35156. Accessed January 12, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma): follow-up care. www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/follow-care. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- Abou-Alfa GK, Sahai V, Hollebecque A, et al. Pemigatinib for previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:671-684.

- Abou-Alfa G, Macarulla T, Javle MM, et al. Ivosidenib in IDH1-mutant, chemotherapy-refractory cholangiocarcinoma (ClarlDHy): a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:796-807.

- Cancer.Net. Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma): about clinical trials. www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/about-clinical-trials. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma): coping with treatment. www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/coping-with-treatment. Accessed March 8, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. The genetics of cancer. www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/cancer-basics/genetics/genetics-cancer. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- Kahl K. FDA grants priority review to infigratinib to treat cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Network. Published December 1, 2020. www.cancernetwork.com/view/fda-grants-priority-review-to-infigratinib-to-treat-cholangiocarcinoma. Accessed February 12, 2021.

- Javle M, Lowery M, Shroff RT, et al. Phase II study of BGJ398 in patients with FGFR-altered advanced cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:276-282.

- Javle MM, Roychowdhury S, Kelley RK, et al. Final results from a phase II study of infigratinib (BGJ398), an FGFR-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with previously treated advanced cholangiocarcinoma harboring an FGFR2 gene fusion or rearrangement. Presented at the 2021 ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium; March 17, 2021. Abstract 265.

- Goyal L, Meric-Bernstam F, Hollebecque A, et al. Primary results of phase 2 FOENIX-CCA2: The irreversible FGFR1-4 inhibitor futibatinib in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) with FGFR2 fusions/rearrangements. Presented at: The Annual Meeting of The American Association for Cancer Research; April 11, 2021. Abstract CT010.

- Zhu A, Macarulla T, Javle MM, et al. Final results from ClarIDHy, a global, phase III, randomized, double-blind study of ivosidenib versus placebo in patients with previously treated cholangiocarcinoma and an isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 3):266-266.

- American Cancer Society. Targeted therapy for bile duct cancer. www.cancer.org/cancer/bile-duct-cancer/treating/targeted-therapy.html. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- Keytruda Prescribing Information. Merck & Co., Inc, Whitehouse Station, NJ. Updated November 2020.

- National Cancer Institute. Coronavirus: what people with cancer should know. National Institutes of Health. www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coronavirus/coronavirus-cancer-patient-information#i-receive-cancer-treatment-at-a-medical-facility-what-should-i-do-about-getting-treatment. Accessed March 12, 2020.

- Mizrahi JD, Gunchick V, Mody K, et al. Multi-institutional retrospective analysis of FOLFIRI in patients with advanced biliary tract cancers. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;12:83-91.

- National Institute on Aging. What are palliative care and hospice care? US Department of Health and Human Services. www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-are-palliative-care-and-hospice-care. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Coping with cancer: what is palliative care? www.cancer.net/coping-with-cancer/physical-emotional-and-social-effects-cancer/what-palliative-care. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Survivorship: nutrition recommendations during and after treatment. www.cancer.net/survivorship/healthy-living/nutrition-recommendations-during-and-after-treatment. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma): survivorship. www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/survivorship. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Survivorship: healthy living after cancer. www.cancer.net/survivorship/healthy-living/healthy-living-after-cancer. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- Acquisto S, Iyer R, Rosati LM, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: Treatment, Outcomes, and Nutrition Overview for Oncology Nurses. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22:E97-E102.

- Pemazyre prescribing information. Incyte Corporation. Wilmington, DE. Accessed January 13, 2021.

- Besser J, Grant B, American Cancer Society. What to Eat During Cancer Treatment. American Cancer Society; 2018.

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition during and after cancer treatment. Eat Right. Reviewed June 17, 2020. www.eatright.org/health/diseases-and-conditions/cancer/nutrition-during-and-after-cancer-treatment. Accessed December 1, 2020.

- Cancer Research UK. Bile duct cancer. Controlling symptoms of advanced cancer. Reviewed March 1, 2018. www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bile-duct-cancer/advanced/controlling-symptoms. Accessed December 4, 2020.

- American Cancer Society. Understanding nausea and vomiting. www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/physical-side-effects/nausea-and-vomiting/what-is-it.html. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Coping with cancer: nausea and vomiting. www.cancer.net/coping-with-cancer/physical-emotional-and-social-effects-cancer/managing-physical-side-effects/nausea-and-vomiting. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- Cancer Research UK. Bile duct cancer. Your diet. Reviewed December 4, 2020. www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bile-duct-cancer/living-with/eating-drinking. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- American Cancer Society. Physical activity and the cancer patient. www.cancer.org/treatment/survivorship-during-and-after-treatment/staying-active/physical-activity-and-the-cancer-patient.html. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Physical activity tips for survivors. www.cancer.net/survivorship/healthy-living/physical-activity-tips-survivors. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- Cancer Research UK. About cancer pain. www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/coping/physically/cancer-and-pain-control/about-cancer-pain. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- Pollock R. Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation. Biliary card – information for the treating physician. May 6, 2014. https://cholangiocarcinoma.org/biliary-emergency-information-card/biliary-card. Accessed December 4, 2020.

- Cancer.Net. Coping with cancer: fatigue. www.cancer.net/coping-with-cancer/physical-emotional-and-social-effects-cancer/managing-physical-side-effects/fatigue. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- Cancer Research UK. Managing your emotions. www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/coping/emotionally/cancer-and-your-emotions/managing-your-emotions. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- Pergolotti M, Williams GR, Campbell C, et al. Occupational therapy for adults with cancer: why it matters. Oncologist. 2016;21:314-319.

- Cancer.Net. Coping with cancer: managing emotions. www.cancer.net/coping-with-cancer/managing-emotions. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- Incollingo BF. Numerous quality-of-life disturbances affect patients with cholangiosarcoma, survey finds. Cure. July 27, 2020. www.curetoday.com/view/numerous-qualityoflife-disturbances-affect-patients-with-cholangiocarcinoma-survey-finds. Accessed December 1, 2020.

- Cancer.Net. Coping with cancer: managing emotions: depression. www.cancer.net/coping-with-cancer/managing-emotions/depression. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Coping with cancer: depression. www.cancer.net/coping-with-cancer/managing-emotions/depression. Accessed March 15, 2021.

- Mehta R, Sharma K, Potters L, et al. Evidence for the role of mindfulness in cancer: benefits and techniques. Cureus. 2019;11:e4629.

- American Cancer Society. Practice mindfulness and relaxation. www.cancer.org/treatment/survivorship-during-and-after-treatment/coping/practice-mindfulness-and-relaxation.html. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Coping with cancer: coping with uncertainty. www.cancer.net/coping-with-cancer/managing-emotions/coping-with-uncertainty. Accessed March 15, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Navigating cancer care: dating and intimacy. www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/dating-sex-and-reproduction/dating-and-intimacy. Accessed March 15, 2021.

- Cancer.Net. Navigating cancer care: understanding the costs related to cancer care. www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/financial-considerations/understanding-costs-related-cancer-care. Accessed Mach 15, 2021.

- Social Security Administration. Benefits for people with disabilities. www.ssa.gov/disability. Accessed February 27, 2021.

- Lee H, Singh GK. Inequalities in life expectancy and all-cause mortality in the United States by levels of happiness and life satisfaction: a longitudinal study. Int J MCH AIDS. 2020;9:305-315.

Resources

Tumor Biomarker Testing

Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation’s “Mutations Matter”:

cholangiocarcinoma.org/mutationsmatter

Staging

Cancer.Net:

www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/stages

National Cancer Institute:

www.cancer.gov/types/liver/patient/bile-duct-treatment-pdq

Finding a Specialist

Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation:

cholangiocarcinoma.org/newly-dx

Questions to Ask Healthcare Team

Cancer.Net:

www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bile-duct-cancer-cholangiocarcinoma/questions-ask-health-care-team

American Cancer Society:

www.cancer.org/cancer/bile-duct-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/talking-with-your-doctor.html

National Cancer Institute:

www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/questions

Anesthesia Information

American Cancer Society:

www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/treatment-types/surgery/recovering-from-cancer-surgery.html

Clinical Trials

Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation:

cholangiocarcinoma.org/professionals/research/clinical-trials

ClinicalTrials.gov:

www.clinicaltrials.gov

Side Effect Management

Cancer.Net:

www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/managing-your-care/cancernet-mobile

Side Effects of Various Therapies

National Cancer Institute:

www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs

MedlinePlus:

medlineplus.gov/druginformation.html

Finding a Palliative Care Team

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization:

The Center to Advance Palliative Care:

www.getpalliativecare.org

Well-Being

Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation:

www.facebook.com/CCFs-Wellness-for-Life-103342318424105/about

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics:

www.eatright.org/find-an-expert

Pain Management

American Society of Clinical Oncology:

www.cancer.net/sites/cancer.net/files/managing_pain_booklet.pdf

Mental Health

Alliance for Quality Psychosocial Cancer Care:

www.cancersupportcommunity.org/alliance-quality-psychosocial-cancer-care

American Psychosocial Oncology Society:

(866) 276-7443; apos-society.org

Association of Oncology Social Work:

aosw.org/patients-caregivers/find-an-osw-near-me

Connecting with Others

Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation:

cholangiocarcinoma.org/cholangioconnect

Financial Support

Cancer Financial Assistance Coalition:

cancerfac.org

Cancer Care:

(800) 813-4673; www.cancercare.org

Cancer Finances:

cancerfinances.org

Social Security Administration:

www.ssa.gov/disability

Patient Support

Cancer Hope Network:

www.cancerhopenetwork.org

Triage Cancer:

triagecancer.org

Cancer Support Community:

www.cancersupportcommunity.org

Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation Patient Advocacy

Melinda Bachini, Director of Advocacy:

(888) 936-6731, extension 8

Dawn Scott, Patient Advocate:

(888) 936-6731, extension 22

Caregiver Support

Cancer Horizons:

www.cancerhorizons.com/caregivers

Cholangiocarcinoma Caregivers:

www.facebook.com/groups/170301816796010

Literature for Individuals with CCA

100 Questions & Answers About

Cholangiocarcinoma, Gallbladder and Bile Duct

Cancers by Dr. Ghassan Abou-Alfa & Dr. Eileen

M. O’Reilly (to request the free book):

cholangiocarcinoma.org/publications

ASCO guide on appetite loss:

www.cancer.net/sites/cancer.net/files/asco_answers_appetite_loss.pdf

National Cancer Institute: Bile Duct Cancer

(Cholangiocarcinoma) Treatment (PDQ®)–

Patient Version:

www.cancer.gov/types/liver/patient/bile-duct-treatment-pdq

Major Cancer Organizations

Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation:

cholangiocarcinoma.org

American Cancer Society:

www.cancer.org

Cancer.Net:

www.cancer.net

National Cancer Institute:

www.cancer.gov

National Comprehensive Cancer Network:

www.nccn.org