Its content was based on a roundtable meeting that was sponsored and moderated by Takeda Oncology. Authors are paid consultants of Takeda Oncology. All trademarks are the property of their respective owners. © 2020 Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

To download this article as a PDF, see the link below.

In 2019, an in-depth Global Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) Patient Advocacy Roundtable was held in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. The goal of this roundtable, which was sponsored by Takeda Oncology, was to provide patient advocates with an opportunity to share their perspectives on the challenges faced by individuals living with higher-risk MDS.

This publication shares the insights of patient advocacy community leaders regarding individuals with higher-risk MDS, including their advice for patients to support shared decision-making, patient education, and patient empowerment approaches. The manuscript is divided into 3 main sections:

- Understanding MDS and Higher-Risk MDS

-

- What Is MDS?

- What Is Higher-Risk MDS?

- Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis of MDS

- Recommendations from Patient Advocates for Individuals Living with Higher-Risk MDS

-

- Treatment Considerations

- Living with Higher-Risk MDS

- Seeking Out MDS Experts

- Communicating Treatment Goals and Sharing Decisions

- Connecting with the Patient Advocacy Community

- Educational Resources for Patients with Higher-Risk MDS

-

- Global Patient Advocacy Organizations

- Glossary of Terms

- Practical Advice and Takeaway Messages

Understanding MDS and Higher-Risk MDS

What Is MDS?

MDS is uncommon for adults in their 50s – and is most commonly diagnosed among those 70 years of age or older.1 In European countries, more than 30,000 individuals are diagnosed with MDS each year.2,3 In the United States, approximately 10,000 individuals are diagnosed with MDS each year.1

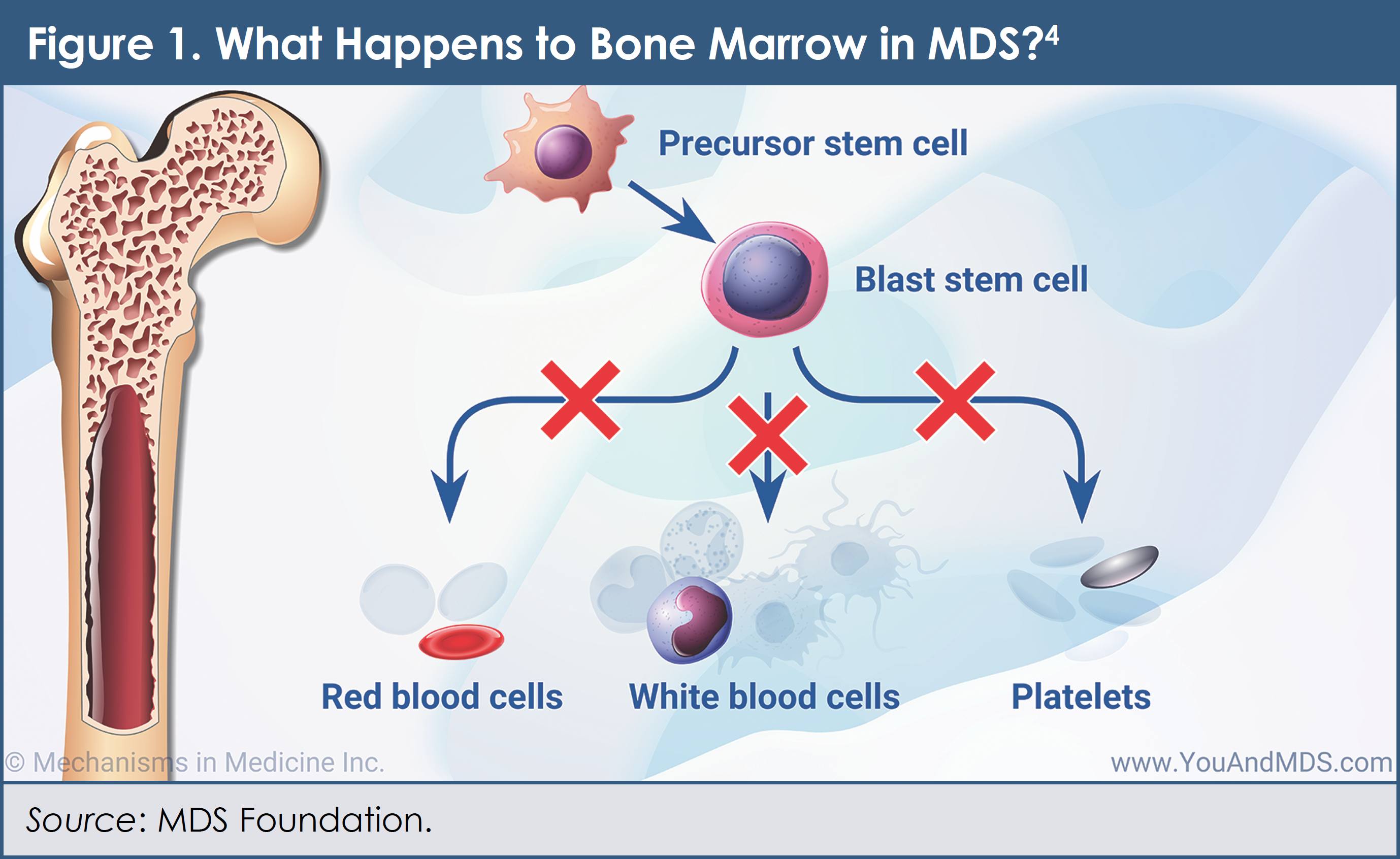

MDS is not one cancer; rather, it is a group of cancers that affects the blood and bone marrow. In MDS, blood cells that are formed in the bone marrow never mature fully to become normal blood cells (Figure 1).4 In a healthy individual, the bone marrow makes “immature” blood cells—which are also known as blasts, or stem cells—that eventually become “mature” blood cells. When you have MDS, your bone marrow does not totally stop working. It still makes blood cells. But it usually makes fewer cells, and the cells it does make don’t always work right. Having a lower-than-normal level of any type of blood cell is called cytopenia and it is possible to have more than 1 cytopenia at the same time. Early on, individuals with MDS may not exhibit any signs or symptoms of the cancer. Later on, however, symptoms can include feeling tired, shortness of breath, easy bleeding and bruising, and frequent infections.5 Sometimes MDS can progress to acute myeloid leukemia (AML)—a more aggressive type of blood cancer in which immature cells increase and grow incontrollably.1

The cause of MDS is not fully understood, but many factors can increase an individual’s risk of developing the cancer. Among the possible causes are having received prior chemotherapy or radiation therapy; exposure to certain chemicals, including tobacco smoke, pesticides, fertilizers, and such solvents as benzene; and exposure to heavy metals, such as mercury and lead.5

"Patients might find it difficult to understand their type of MDS and treatment options. This means that they may not ask the right questions."

—Sophie Wintrich, MDS UK Patient Support Group (United Kingdom)

What Is Higher-Risk MDS?

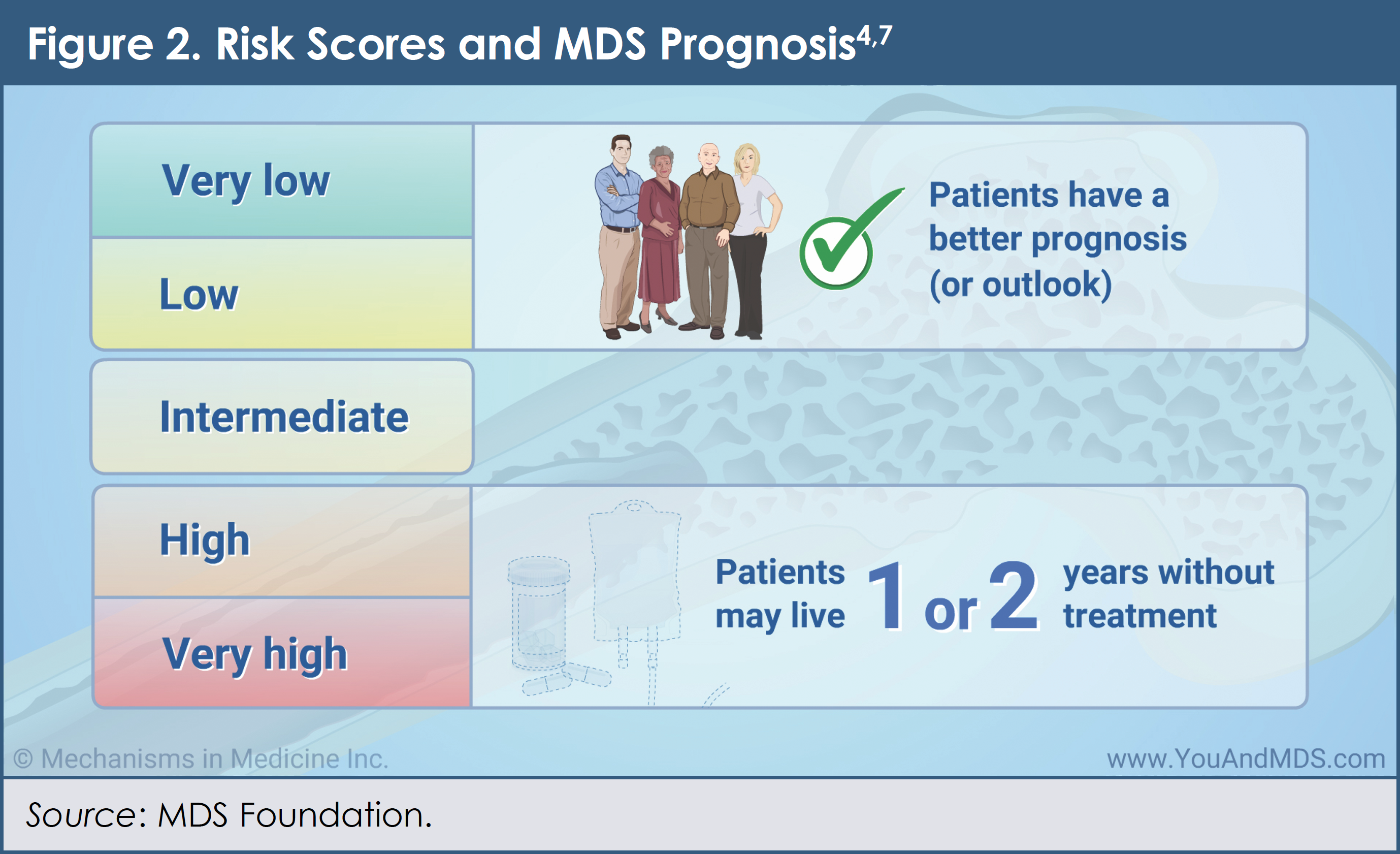

There are many different types of MDS. Specialists (oncologists and hematologists) who treat patients with MDS typically evaluate the bone marrow (using a bone marrow aspiration and biopsy) and the blood cells (using various blood tests) to determine which type of MDS a person has.1 Physicians also use a scoring system, called the Revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R), to help place individuals with MDS into 1 of 5 distinct risk groups. The 5 risk groups include “very low risk,” “low risk,” “intermediate risk,” “high risk,” and “very high risk.”1

MDS medical experts and patient advocates emphasize the importance of individuals with MDS learning their risk category. Patients with MDS who are in the higher-risk categories (ie, “intermediate risk,” “high risk,” and “very high risk”) may require different types of treatments compared with those with “lower-risk” MDS, based on their IPSS-R score.6

Figure 24,7 shows the IPSS-R categories and provides general information about the outcomes associated with each broad group (ie, higher-risk and “lower-risk” MDS). Note that patients’ overall experience with MDS depends not only on the type of MDS that they have and on their risk group, but also on their overall health, age, and life goals for the future.1,8 Physicians who treat patients with MDS should consider a person’s IPSS-R risk score at the time of diagnosis.6

As shown in Figure 3,4 some patients with higher-risk MDS require treatment right away.6 Every individual with MDS may receive supportive care as well, including routine monitoring of blood cell counts and, in some cases, blood transfusions, as directed by their healthcare team.8

Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis of MDS

Some types of lower-risk MDS progress slowly and cause either no signs or symptoms or mild to moderate ones, such as anemia—that is, a low number of red blood cells (RBCs)—and changes in other types of blood cells.1,9 Other types of MDS, particularly higher-risk MDS, can be associated with severe problems. For example, patients with higher-risk MDS can have severe deficits in RBCs, white blood cells, and platelets. These low blood counts can lead to anemia; neutropenia (low neutrophil counts, which affect the body’s ability to fight infection); and thrombocytopenia (low platelet counts, which affect the body’s ability to help the blood to clot).9

Because blood counts are affected in patients with MDS, signs and symptoms can include shortness of breath, feeling tired, skin that is paler than usual, frequent infections, easy bruising or bleeding, and petechiae (round, flat, pinpoint spots caused by bleeding under the skin).1,5

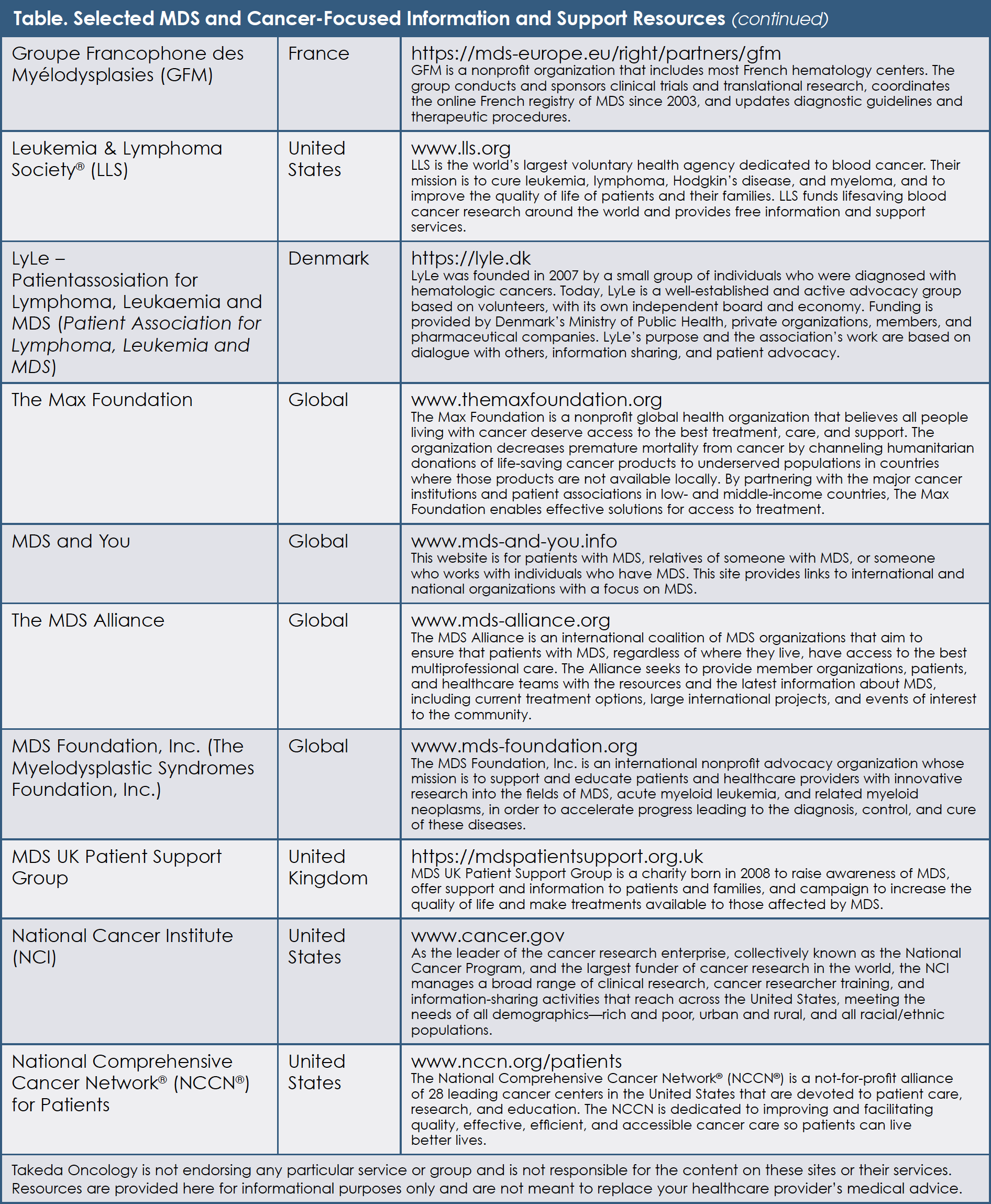

Patient advocacy groups and other organizations, however, have developed easy-to-read educational materials in multiple languages for individuals who want to learn more. Readers should refer to the trusted and patient-friendly websites represented by the roundtable advocates, as well as the MDS Alliance and the National Cancer Institute. A comprehensive list of MDS resources is provided in the Table.

Recommendations from Patient Advocates for Individuals Living with Higher-Risk MDS

Treatment Considerations

According to global leaders of MDS patient advocacy groups, it is important for patients with higher-risk MDS to understand the types of treatments that are available to them and how these treatments can impact their daily lives. MDS experts agree that treatment decisions for individuals with higher-risk MDS should be shared between the healthcare team and the patient with MDS (as well as with the patient’s care partners).6 Patients should do their own research. A good and honest relationship with their physician is crucial. Patients, especially those with higher-risk MDS, need to be honest and upfront with their physicians about their feelings and concerns.1

MDS patient advocacy leaders are concerned that those individuals with higher-risk MDS who do not understand their cancer and subtype may not receive the right treatment at the right time, which can lead to poorer outcomes and shorter survival.

"I know a lot of grandparents who cannot spend a lot of time with their grandchildren because of their weak immune systems. People are afraid to hug people or shake hands because they're afraid to get sick. MDS removes you from people; it is alienating."

—Jacqueline Dubow, Connaître et Combattre les Myélodysplasies (France)

An Internet-based survey, which was conducted among individuals living with MDS, demonstrated that participants in the MDS Patient Advocacy Roundtable are correct: Most patients with MDS have a limited understanding of their cancer, the subtype, and treatment goals. Of the 358 individuals with MDS who responded to the survey, more than half (55%) did not know their IPSS-R risk score or category.10 In addition, 42% were unaware of their bone marrow blast percentage and 28% did not know their cytogenetic status.10 A large percentage of patients in this survey also reported that their MDS was first described to them as a “bone marrow disorder” (80%) or “anemia” (56%).10 Only a few patients recalled that their MDS was described as a “cancer” (7%) or “leukemia” (6%).10

MDS patient advocacy leaders realize that MDS physician experts often initiate treatment immediately in patients who have been diagnosed with higher-risk MDS. The goals of such therapy are to delay transformation to AML, to improve survival, if possible, and to reduce the impact of any MDS-related symptoms on patients’ quality of life.8

"If you have higher-risk MDS and you're reading materials about MDS that relate only to lower-risk MDS, you might think everything is fine, but this might not be true. You need information that relates to your specific situation."

—Cindy Anthony, Aplastic Anemia & Myelodysplasia Association of Canada (Canada)

Patients with higher-risk MDS can be treated with a hypomethylating agent (HMA). These medications are a form of chemotherapy that kill cells that are dividing rapidly. In some individuals with higher-risk MDS, treatment with an HMA can improve blood counts, lower the risk for leukemia, and may prolong life. Further, RBC counts may improve sufficiently to stop transfusions. As with all medications, HMAs are associated with certain side effects, including fatigue and temporarily lowering blood counts.9

To relieve symptoms of higher-risk MDS caused by low blood counts, supportive care is also important.5 Supportive care, which may include blood transfusions, helps to improve patients’ quality of life. Blood transfusions restore blood counts to more normal levels when blood cell counts are too low. Patients can receive transfusions of RBCs or platelets.5

"In the MDS Foundation's survey of patients with MDS, we learned that about 40% [of patients] don't know their subtype at diagnosis. Even later, after living with MDS for some time, 30% still don't know their subtype."

—Tracey Iraca, MDS Foundation (United States)

The benefits of supportive care are generally temporary, however, as these approaches do not affect the underlying cancer—that is, MDS.8

- Patients who require RBC transfusions often have a low number of RBCs, as well as signs and symptoms of anemia, including shortness of breath, feeling very tired, and pale skin5

- Platelet transfusions are usually administered when a patient’s platelet count is very low. Individuals with higher-risk MDS who have low platelet counts can experience bleeding or bruising5

It is important to realize that receiving multiple blood transfusions may also cause side effects. Patients who receive many blood transfusions can experience tissue and organ damage over time. This results from a buildup of iron in their bodies, which is called iron overload. For some patients, iron chelation therapy is prescribed to remove this extra iron.5

"Today's treatment for higher-risk MDS aims to keep the disease in check, so that it doesn't progress to leukemia. Treatment can also help with anemia and fatigue. One of the goals for an individual with higher-risk MDS is really improvement in his or her quality of life."

—Niels Jensen (Denmark)

Depending on the severity of their cancer and the percentage of blasts in their bone marrow, some patients with high-risk or very-high-risk MDS can benefit from allogeneic stem-cell transplantation (ASCT)—a procedure in which a person’s blood-forming cells are replaced by cells from a donor.1,5

In addition to the use of HMAs and other medications, MDS patient advocacy leaders are aware of several important potential future treatment options that are being investigated by drug developers and researchers. Because currently only a few treatments are available for patients with higher-risk MDS, those with cancer that worsens despite standard treatments are encouraged to talk to their physician about enrolling in a clinical trial.6 Clinical trials are often designed to test a new treatment to learn whether or not the benefits of the product or treatment outweigh the known risks for the intended use, and in some cases whether it is a better option than the treatments that are currently being used. Clinical trials can evaluate new agents, different combinations of existing therapies, new approaches to ASCT, and other novel methods of treatment for those with higher-risk MDS.1

Patient advocates recommend that in order to learn more about treatment options, individuals with higher-risk MDS speak with their physicians and visit websites that are managed by MDS organizations, as well as the MDS Alliance and the National Cancer Institute. A list of these MDS resources is provided in the Table.

Living with Higher-Risk MDS

MDS patient advocacy leaders appreciate the fact that compared with patients with lower-risk MDS, those who have higher-risk MDS can experience more symptoms: they can feel very tired, short of breath, bruise easily, and have a higher risk for infection. Each of these challenges can affect patients’ ability to perform their daily activities, their desire or ability to socialize, and their overall quality of life. Some individuals with higher-risk MDS also have difficulty dealing with certain emotions, such as sadness, anxiety, or anger, and with managing their levels of stress. Patients may have difficulty telling their loved ones how they feel. Others in their family may not know how to respond to their loved one with higher-risk MDS.1

It is important for patients with higher-risk MDS, their family members, and their care partners to use the many resources that are available, in order to help them cope with their cancer, as well as with any cancer- and treatment-related side effects that may occur. Individuals with higher-risk MDS and their care partners should report any possible side effects of treatment to their healthcare team, even if those effects do not appear to be serious (see below on the role of the care partner). These discussions should include not only physical side effects, but emotional and social (isolation) effects of MDS as well.1

The Role of the Care Partner

Family members and friends can play a valuable role in caring for an individual with MDS. This is what it means to be a care partner. Care partners help patients by providing physical, practical, and emotional support, even if they live far away. Care partners may be responsible for several different things, either on a daily or on an as-needed basis. Some of the tasks that might be assigned to care partners include the following1:

- Providing emotional support and encouragement

- Communicating with the healthcare team

- Administering medications on schedule

- Helping to manage patients’ symptoms and side effects

- Arranging medical appointments

- Providing transportation to and from appointments

- Preparing or serving meals

- Assisting with household chores

- Managing insurance and billing issues

Patient advocates encourage individuals with MDS, as well as their care partners and family members, to speak with their physicians, nurses, social workers, and other members of the healthcare team about how they feel. Advocates suggest that talking with other patients who have MDS can also be valuable. Patient organizations, including those listed in the Table, can help patients and care partners connect with others to find the support that they need.

Regardless of whether they are receiving treatment, all patients with MDS—particularly those with higher-risk cancer—require close monitoring by their healthcare team. Monitoring includes complete blood counts and other tests that measure the amount of blasts, along with determining whether a patient’s cancer has changed in any way. For example, a higher percentage of blasts in the blood or bone marrow can be a signal that higher-risk MDS is transforming to AML. If this occurs, a different treatment approach might be needed.9

"We had a patient who told us that he hadn't seen his grandkids in months because he was afraid. The grandkids were toddlers, and he said they were afraid to have them over to the house because they are always sick with something. They would come to visit, but stand on the sidewalk and talk through the window."

—Neil Horikoshi, Aplastic Anemia and MDS International Foundation

Seeking Out MDS Experts

All participants in the Global MDS Patient Advocacy Roundtable agree that it is important for patients with MDS and their physicians to learn about the risk of transformation to AML. Because higher-risk MDS is a complex condition, advocates believe that individuals with the cancer should find and meet with a physician who has specific expertise in managing their cancer.

"Seeing a physician expert in MDS is so important. Patients who go to an expert center are going to have support for all of the different aspects of their MDS and of their lives: their treatment, their nutrition, their mental health...everything."

—Niels Jensen (Denmark)

The roundtable participants explained that physicians who are experts in MDS are trained hematologists and oncologists who typically practice in larger cancer centers or university hospitals. Experts in MDS often treat only patients with blood cancers and see large numbers of patients who have been diagnosed with MDS. Additionally, experts generally have in-depth knowledge of ongoing research in MDS and access to clinical trials that are testing novel treatments for patients with MDS, including those with higher-risk subtypes. Because of logistics and other challenges, several roundtable leaders noted that referrals to MDS physician experts are either not occurring at all or are happening “late”—that is, after 1 or more treatments have been tried.

"People with cancer, including those with higher-risk MDS, should never feel guilty or wrong about getting a second opinion or being curious about what could happen to them as the disease progresses. To help them get over that guilt, I tell patients that the second opinion is helpful because it more often confirms that your first doctor is doing the right thing."

—Sophie Wintrich, MDS UK Patient Support Group (United Kingdom)

Patients with MDS, particularly those newly diagnosed with higher-risk cancer, are strongly encouraged to consult with experts in the field regarding any questions they might have about their cancer and their treatment. As with any medical condition, several ways to approach patient care typically exist, and physicians can have different opinions about the best standard treatment plan.1

Resources that can help individuals with MDS and their care partners find physician experts in the cancer are listed in the Table.

Communicating Treatment Goals and Sharing Decisions

The concept of shared decision-making means that the individual with cancer and his or her care partners work together with the healthcare team to make treatment decisions. Shared decision-making is particularly important when several options are available to consider; a patient’s personal preferences and values can help the team determine which treatment option best meets his or her goals.11

"Many patients don't challenge their physicians. They're afraid to do that. They don't feel that they are empowered to do that, but they are!"

—Jana Pelouchová, Diagnoza Leukemie (Czech Republic)

MDS patient advocates believe that shared decision-making can result in positive outcomes among individuals with cancer. They are also aware of barriers to shared decision-making, however, with some patients and care partners expressing hesitancy or feeling guilty about asking questions or seeking second opinions from MDS experts. Patient advocates at the roundtable discussion reinforced the importance of patients and care partners staying informed, asking questions, and sharing their preferences and needs. The treatment plan for a patient with higher-risk MDS should be personalized or tailored to his or her cancer subtype and risk status, as well as to the patient’s specific wishes and goals.

Connecting with the Patient Advocacy Community

Even though MDS is rare, many advocacy groups and support organizations are located throughout the world. The experts who participated in the Global MDS Patient Advocacy Roundtable convened from around the world as leaders of these types of organizations. They and their colleagues devote their time and energy to ensure that all patients with MDS have the information, guidance, resources, and support that they need to live well with their cancer.

"Patients with higher-risk MDS and their loved ones should always feel that their needs and wishes are being met throughout the treatment journey."

—Cristina Panera Hernández, Asociación Española de Afectados por Linfoma (Spain)

Members of the roundtable who have been involved with advocacy for many years have noted that organizations such as theirs have become even more important over time. They see that today’s families are smaller, with fewer generations living under one roof or in the same town or locale. Advocates are grateful that they can talk with and assist patients with MDS who are less able to rely on family members for support and information.

"If your type of MDS puts you at higher risk of transforming to AML, please speak up when talking to your doctors and other healthcare providers. Let them know what is important to you."

—Jana Pelouchová, Diagnoza Leukemie (Czech Republic)

Patient organization leaders are also passionate about giving people with MDS the power to advocate for themselves. Roundtable participants want patients with higher-risk MDS to feel knowledgeable and confident when speaking with their physicians and sharing their wishes and goals. Many of the advocacy organizations represented in the roundtable coordinate support group meetings in towns and cities around the world, in order to help people with MDS gain those skills and learn from others who have been “in their shoes.”

"Historically, I think we had stronger family networks. If somebody was ill, the family rallied. This is less true these days. We have smaller family networks available at the patient's doorstep. People with cancers such as MDS are more likely to have to rely on outside help...outside resources."

—Cristina Panera Hernández, Asociación Española de Afectados por Linfoma (Spain)

Participants in the Global MDS Patient Advocacy Roundtable closed the meeting by reinforcing their readiness to speak with and support individuals with higher-risk MDS who have questions or need resources. They strive to help all patients with MDS, particularly those living with higher-risk cancer, to obtain the best-quality medical care and feel confident about the choices that they have made throughout their individual journey with this cancer.

"Support meetings empower people with MDS to speak up for themselves. Instead of putting somebody there to do a talk and so on—which keeps the patients passive—we give them a role in moderating and coordinating these meetings with our guidance. We want people to realize that they can do that. We have found that it is extremely freeing; it is like a cathartic experience for people. It helps them realize that they are not victims of MDS. They have an important role to play, and they can help other people with MDS."

—Cindy Anthony, Aplastic Anemia & Myelodysplasia Association of Canada (Canada)

Educational Resources for Patients with Higher-Risk MDS

Global Patient Advocacy Organizations

Educational resources and support for individuals with MDS are available both online, as well as at local hospitals, libraries, and community centers. For patients with MDS and their families, national and international support groups can be valuable sources of information and assistance (see Table).

Glossary of Terms

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML): An aggressive and fast-growing disease in which too many immature white blood cells (known as myeloblasts) are found in the bone marrow and blood

Allogeneic stem-cell transplantation (ASCT): A procedure in which a person receives blood-forming stem cells (cells from which all blood cells develop) from a genetically similar, but not identical, donor. This is often a sister or brother, but it can be an unrelated donor.

Anemia: A medical condition in which a person’s red blood cell count, or hemoglobin, is below normal

Aplastic anemia: A disorder in which the bone marrow is unable to produce blood cells

Blasts: Abnormal (dysplastic), immature blood cells found in the bone marrow or peripheral blood. Because blasts are not mature, these cells are unable to perform their intended function. AML develops from blasts.

Blood cell count: A measure of the number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets in the blood. The amount of hemoglobin (the substance in the blood that carries oxygen) and the hematocrit (the amount of whole blood that is made up of red blood cells) are also measured. A blood cell count is used to help diagnose and monitor many conditions, such as anemia, dehydration, malnutrition, and leukemia. It is also called a CBC, or complete blood count.

Blood transfusion: A procedure in which whole blood or one of the components of blood is administered to a person through an intravenous (IV) line into the bloodstream. This is a method of replacing a patient’s red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets that were destroyed by a disease or damaged by a treatment.

Bone marrow: Soft, sponge-like tissue in the center of most bones that produces white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets

Chemotherapy: Treatment for cancer that stops the growth of cells

Clinical trial: A medical research study that involves patients, with the aim being to improve treatments and their side effects; patients must always be informed if their treatment is part of a clinical trial

Cytogenetics: The study of chromosomes or DNA—the part of the cell that contains genetic information; some cytogenetic abnormalities, such as deletion 5q, are linked to different forms of MDS

Genomics: The study of genes and their functions, which is increasingly important for learning the likely outcome or prognosis of the various subtypes of MDS. In the future, this information may also help to personalize MDS treatments.

Hemoglobin: A protein in red blood cells that picks up oxygen in the lungs and brings it to cells in all parts of the body

Hypomethylating agent (HMA): A form of chemotherapy used to treat MDS that affects the way in which genes are controlled, by slowing down genes that promote cell growth and killing cells that are dividing rapidly.

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS): A group of cancers in which the bone marrow does not produce enough normal blood cells (white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets), such that there are abnormal cells in the blood and/or bone marrow. When there are fewer healthy blood cells, infection, anemia, or bleeding may occur. MDS can progress to acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Neutropenia: A condition in which the number of neutrophils (a type of white blood cell) in the bloodstream is decreased

Neutrophil: A type of white blood cell that helps to fight infection

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH): A rare, life-threatening disorder in which red blood cells are easily destroyed by certain immune system proteins. Symptoms can include blood clots and red or brownish urine in the morning.

Platelet: A disc-shaped element in the blood that assists in blood clotting. During normal blood clotting, platelets clump together (aggregate). Although platelets are often classed as blood cells, they are actually pieces of large bone marrow cells, called megakaryocytes.

Red blood cell (RBC): A type of blood cell that is made in the bone marrow and found in the blood. RBCs contain a protein called hemoglobin that carries oxygen from the lungs to all parts of the body. RBCs are also called erythrocytes.

Revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R): A classification system used as a standard for evaluating the prognosis outlook of patients with MDS; the 5 distinct risk groups per IPSS-R include very low risk, low risk, intermediate risk, high risk, and very high risk7

Stem cells: Cells that have the potential to develop into many different or specialized cell types

Supportive care: Care given to improve the quality of life of patients who have a serious or life-threatening disease. The goal of supportive care is to prevent or treat, as early as possible, the symptoms of a disease; the side effects associated with the treatment of a disease; and the psychological, social, and spiritual problems related to a disease or to its treatment. Supportive care is also called comfort care, palliative care, and symptom management.

Thrombocytopenia: A condition in which the number of platelets in the bloodstream is lower than normal

White blood cell: A type of cell that is produced in the bone marrow to help fight infection. There are several different types of white blood cells.

Glossary Sources: NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms and MDS UK “Understanding MDS”

Practical Advice and Takeaway Messages

- At diagnosis, patients with MDS are categorized based on their risk for progression to AML. To determine the risk score according to IPSS-R, the physician uses the patient’s blast percentage, cytogenetic risk group, blood counts, and other test findings.6

- Higher-risk MDS may change (transform) to AML—an aggressive type of leukemia. Patients with higher-risk MDS have a shorter survival time than do those with lower-risk MDS.9

- All patients with higher-risk MDS should be well informed about the seriousness of their cancer. Knowing this risk, patients can discuss with their physicians the role of specific treatments, clinical trials, and ASCT for higher-risk MDS.6

- Regardless of whether they are receiving treatment, all people with MDS—particularly those with higher-risk cancer—should be closely monitored by their healthcare team. Complete blood counts and other tests can help physicians learn if and how a patient’s MDS has changed.

- Patients with higher-risk MDS should feel empowered to speak up (or advocate) for themselves with their physicians and other healthcare providers. Individuals who have a serious cancer, such as higher-risk MDS, should never feel guilty or wrong about getting expert opinions (including second opinions) or being curious about what happens as their cancer progresses.

- Although MDS is rare, many organizations offer clearly written educational materials in multiple languages about this type of cancer, its diagnosis, and its treatment. These organizations also provide comprehensive emotional support for patients with MDS and their care partners, and advocate for continued MDS research.

References

- Cancer.net. Myelodysplastic Syndromes - MDS - Introduction. www.cancer.net/cancer-types/myelodysplastic-syndromes-mds/view-all. Accessed August 9, 2019.

- Neukirchen J, Schoonen WM, Strupp C, et al. Incidence and prevalence of myelodysplastic syndromes: data from the Düsseldorf MDS-Registry. Leuk Res. 2011;35:1591-1596.

- HARMONY Alliance website. Myelodysplastic Syndromes. www.harmony-alliance.eu/en/focus/myelodysplastic-syndromes. Accessed September 9, 2020.

- MDS Foundation. You and MDS: Understanding Myelodysplastic Syndromes. www.youandmds.com/en-mds/view/m101-s01-understanding-myelodysplastic-syndromes-slide-show. Accessed September 3, 2020.

- National Cancer Institute website. Myelodysplastic Syndromes Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version. www.cancer.gov/types/myeloproliferative/patient/myelodysplastic-treatment-pdq. Accessed September 3, 2020.

- Sekeres MA, Cutler C. How we treat higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2014;123:829-836.

- Greenberg PL, Tuechler H, Schanz J, et al. Revised International Prognostic Scoring System for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;120:2454-2465.

- MDS Foundation. Building Blocks of Hope. www.mds-foundation.org/bboh. Accessed September 4, 2020.

- Johns Hopkins University website. Myelodysplastic Syndrome. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/kimmel_cancer_center/types_cancer/myelodysplastic_syndrome.html. Accessed September 4, 2020.

- Sekeres MA, Maciejewski JP, List AF, et al. Perceptions of disease state, treatment outcomes, and prognosis among patients with myelodysplastic syndromes: results from an Internet-based survey. Oncologist. 2011;16:904-911.

- Butow P, Tattersall M. Shared decision making in cancer care. Clinical Psychologist. 2005;9:54-58.

USO-NON-0128