To download this article as a PDF, see the link below.

CPS1428

What Is a Cancer Caregiver?

The Journey of a Cancer Caregiver

How a Caregiver Can Get Informed

Caregiver Perspectives on Gaps and Barriers to Cancer Care

Improving Cancer Outcomes

Self-Care: Caring for the Cancer Caregiver

Resources

A cancer diagnosis not only affects the person with cancer, but also his or her family, coworkers, friends, and pets. Caregivers of people with cancer have an especially difficult job. They provide emotional and physical support and are critical members of the care team alongside healthcare providers. How does someone learn how to be a good caregiver for a person with cancer? What skills are most important? How can caregivers care for themselves?

In May 2018, 8 caregiver advocates who currently care for (or have cared for) someone with cancer met in Cambridge, MA, to take part in a Cancer Caregiver Roundtable, which was moderated and sponsored by Takeda Oncology. During the roundtable meeting, participants shared their personal journeys as caregivers—describing the unique social and cultural factors that shaped their experiences, as well as the skills and behaviors they found most valuable.

Inspired by the candid insights and practical advice that these participants shared with honesty, strength, humor, and, above all, an unwavering love for their “person,” this white paper provides an overview of the unique journey of a cancer caregiver, and features special spotlight sections on caring for individuals with lung cancer.

Participants recount their missteps, triumphs, stressors, frustrations, and joys. They are people who learned firsthand that caring for someone with cancer is neither easy nor predictable. These caregivers now use the knowledge and insights that they gained to become strong advocates for other people with cancer and their caregivers. It is the hope of these roundtable participants that their experiences can empower others who may be feeling vulnerable or overwhelmed by the emotions and responsibilities that come with caring and advocating for a family member or friend with cancer.

What Is a Cancer Caregiver?

Cancer caregivers help their loved ones who have been diagnosed with cancer to learn about their condition and to cope with daily needs.1 Caregivers may help with needs such as traveling to doctor’s appointments, preparing meals, talking through the patient’s questions and feelings, and learning about treatment options.1

“Caregivers should know that they are extremely important. I would tell them, ‘You’re about to get a lot of new information, a whole new vocabulary. You’re a vital part of this journey, and you’re going to be a different person after it.’”

—Chris Draft

The Journey of a Cancer Caregiver

New and Evolving Roles

The process of becoming a cancer caregiver can create a shift in roles and relationships. Many of the caregivers described feeling unprepared; learning on the job; struggling and worrying about “getting it right.” There were 2 AM tears, laughs, coffee, and naps. There were days they wanted help from others, and days they could not be around anyone. However, the caregivers were, and continue to be, clear-eyed about their choice to take on this role and grateful for the lessons the caregiver journey brought them—even when it may have been difficult.

“When my husband was diagnosed with cancer, we had kids in elementary school. I was a stay-at-home mom. I had to do a juggling act, and I was definitely ill-prepared.”

—Kimberly Hall Alexander

“I feel like my whole life was a training ground for me to take care of [my husband]. I knew what to do. I threw myself into research, and we went to see an expert in lung cancer immediately.”

—Kristine Cherol

Roundtable participants included adult children, spouses, and parents. Not surprisingly, they had a variety of experiences related to relationships: navigating distinct roles as cancer caregivers—nurse, lover, friend, advocate, educator, and case manager. Also, caregivers’ responsibilities shifted based on the types of treatments required (potential side effects; how often the medicine had to be taken; the mode of administration [eg, oral, intravenously, in the office, at home]), as well as scheduling and travel logistics to be managed.

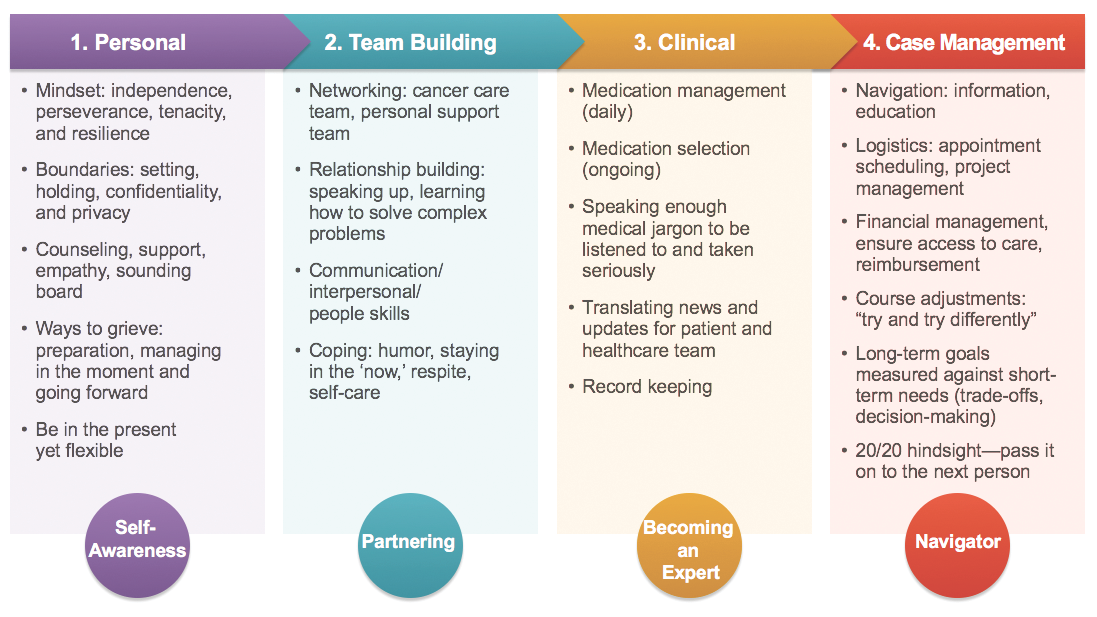

Learning New Skills

Caregivers had to learn how to communicate with their loved ones and the healthcare team, sometimes acting as the liaison between the two. They also had to become informed on the appropriate medical terms so as to be an equal and active member of the care team. Caregivers often become the translators between the patient and the cancer care team, or the patient and the rest of the family. As their loved ones’ circumstances change, caregivers may be faced with new and distinct challenges that require a wide variety of skills. Figure 1 lists many of these skills and explains how they can be helpful.

“My mother, my husband, and my ex-husband have been diagnosed with cancer. I care for all of them. How do we cope? Primarily through humor.”

—Renee Martin Anderson

Mom: “I am Jillian’s mom, and moms can fix anything. Moms make it all go away, right? I struggled with my role as caregiver and my role as her mom.”

—Ros Miller

Nurse/Spouse: “It was hard to switch from being a nurse to being a spouse, especially when I was worried about my husband and how he was doing.”

—Kimberly Hall Alexander

Ramping Up to Full Time: “My husband didn’t need much physical caregiving at the beginning. He had only minor side effects with the targeted therapy. Then things changed when he started chemotherapy. After those physical and emotional changes, caregiving became a 24/7 job for me.”

—Kristine Cherol

“Speaking medical jargon helps you to be taken seriously by the healthcare team. It should not have to be the case, but I found time and time again that it is.”

—Danielle Pardue

Unique Journeys—A Surprising Finding

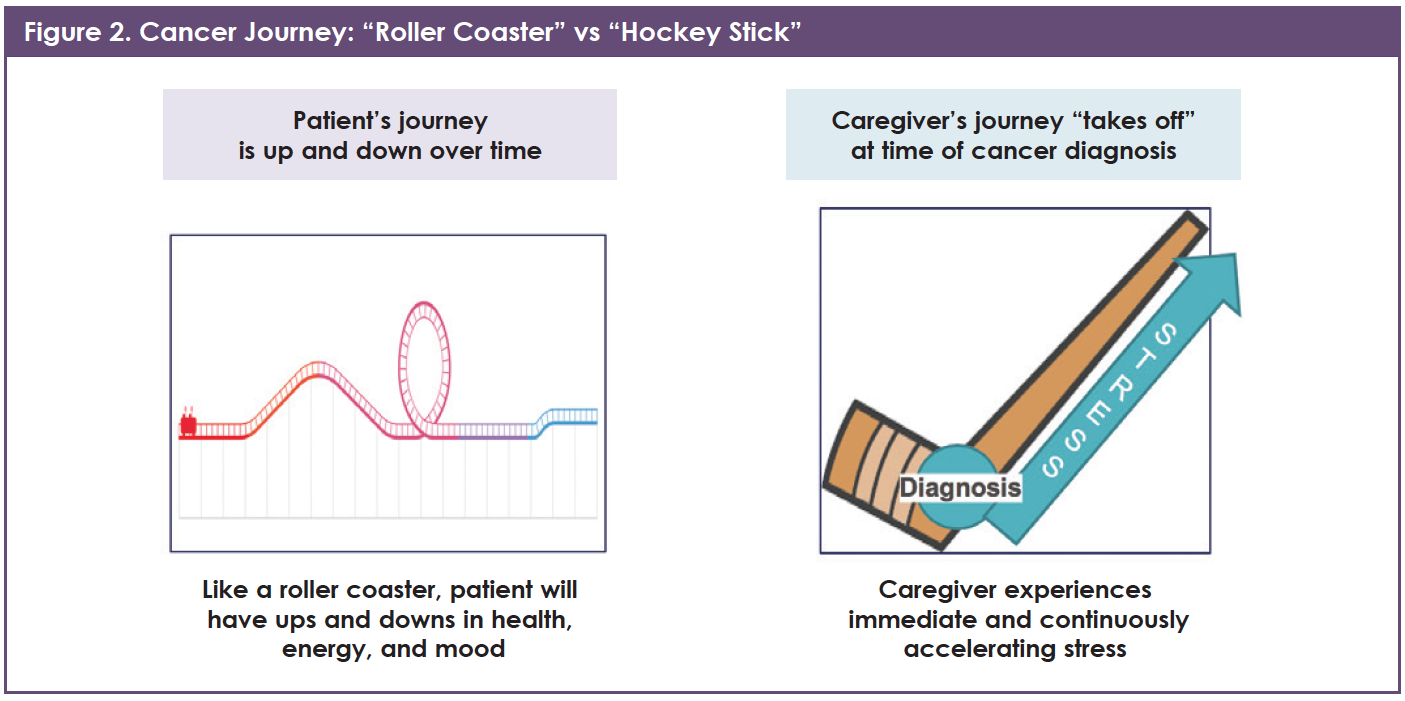

Many people think that the caregiver’s journey mirrors that of the patient’s—a roller coaster, changing day by day in intensity. This was not true for many of the caregivers of patients with cancer who participated in the roundtable. In contrast to the patient journey, which may be a series of ups and downs, the participants reported that the caregiver’s journey instead progresses like a hockey stick. The moment of diagnosis is the pivot point where the blade and the handle meet (Figure 2). From that moment forward, caregivers are under increasing stress that does not end if their loved one passes away, but rather is the basis of the transition to a “new normal.”

How a Caregiver Can Get Informed

Pros and Cons of Internet Searching

The Internet—including “Doctor Google”—provides an amazing (and overwhelming) amount of information. Some of this information is reliable and up-to-date, and some of it is incomplete or false. Although some caregivers gleaned valuable insights from the Internet that helped them translate the information from their healthcare teams, others were turned off or disappointed by what they found online.

“I regretted becoming ‘Google, MD.’ Some of the information I found was not completely accurate. Some of the information was good. It helped me feel more equipped when I was talking with doctors, but you can easily overdo the enormous information highway and I think I overdid it.”

—Ros Miller

Remember:

- Being a caregiver for a loved one with cancer may be hard, wonderful, and scary—rewarding beyond measure. It may change your relationship with your loved one. It may change who you are and who you decide to become over time.

- The caregiver’s journey is often different from the patient’s journey. The caregiver needs skills that come into play at different times along the journey. Seek support and answers. Develop a system to organize the important information.

- Tap into the advice and skills that other caregivers can offer. Lean on others who have already been, or are going through, this journey. They can be your guide.

- There is a lot of cancer-related information on the Internet.

- Look for credible sources to find the most accurate and up-to-date information (see Resources).

- Reliable educational information may come from unexpected sources, including pharmaceutical company websites. Most cancer medications’ websites have the latest information about their uses, safety, financial assistance, and other support resources.

- Most importantly, consult with your healthcare providers when you have questions about symptoms or treatment options.

Spotlight on Lung Cancer

Information Gaps About Lung Cancer

Specifically, for the caregivers in the roundtable who cared for people living with lung cancer, there was a sense of frustration that so much of the information “out there” on the web includes “stop smoking” messages. What seemed to be missing, in their minds, was more current information about the increasing number of patients who have lung cancer but who have never smoked. This group of caregivers, many of whom cared for relatively younger people whose lung cancer was caused by a genetic mutation as opposed to smoking, felt strongly that blaming the victim with messages like “because you smoked, you gave this cancer to yourself,” needs to end.

“You can be diagnosed with lung cancer even if you don’t smoke! My mother didn’t smoke, and she was diagnosed. She had a specific mutation. I remember hearing on NPR that lung cancer could be eradicated if people would stop smoking. That’s not true!”

—Georgeta Lester

Lung Cancer Educational Materials

Based on feedback from those who participated in the roundtable discussion, patients with cancer and their caregivers should look for educational materials that have been created or sponsored by reputable organizations, and make sure that they can verify the source of the information. The group identified several messages about lung cancer that are often not included (or downplayed) on websites and in other materials that are directed to patients with cancer and their caregivers:

- Lung cancer is frequently diagnosed in younger people who never smoked

- People who get lung cancer should not be blamed

- It is important to get genetic and biomarker testing

- Clinical trials in patients with active cancer do not give typical placebo treatment (sugar pill instead of active drugs). In these trials, the placebo group receives the best available, or standard-of-care, treatment

- Financial assistance, including copay assistance, is available from pharmaceutical companies, nonprofit agencies, and even hotel chains (eg, American Cancer Society’s Hope Lodge® and Extended Stay America’s Hotel Keys of HopeTM) to help patients with cancer and their families.

Remember:

- Lung cancer may occur in younger people who have never smoked.

- We should not play the “blame game’’; schools, the media, and advertising can and should do better.

Caregiver Perspectives on Gaps and Barriers to Cancer Care

Inequality in healthcare, including cancer care, can occur for many reasons, including a bias against certain groups of people based on race, ethnicity, education, having another disability, religious beliefs, English language skills, or even the type of cancer they have (see Lung Cancer Stigma and Lack of Research Funding).2-4 Some caregivers participating in the roundtable recalled difficulties with accessing the cancer care system for their loved ones. Others found that their healthcare team was accessible in ways that surprised them.

“If we were having rash issues, which can happen for people who are taking targeted drugs for cancer, we would talk with the nurses. We would also e-mail our doctor.”

—Kristine Cherol

Language Skills and Culture

When people with cancer are immigrants and English is not their native language, they may find it more difficult to communicate. They may also have cultural beliefs and customs that can be barriers to care. Some people may hide their cancer diagnosis. Others do not volunteer that they are having treatment-related side effects. They may not want to talk about signs that suggest that their disease is worsening. Because medical interpreters are underused, patients who are not fluent in English may find it difficult to understand what doctors are telling them and may be less likely to participate in treatment decisions.5

One of the roundtable participants shared her experience, explaining that the burden of talking with the cancer care team fell squarely on her:

“We are originally from Moldova in Eastern Europe. My mother was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer [while in Europe]. She had always lived in Europe and had never been sick. You don’t use the word cancer there. It’s a disease. For her, coping was pretending she didn’t have cancer. My mom’s English is not great; she couldn’t understand medical terms. So I had to interpret for her while trying to process all of the information [at the same time].”

—Georgeta Lester

Remember:

- Caregivers, friends, and family members, as well as healthcare professionals, should realize that many barriers can limit patients’ access to high-quality cancer care, including biases related to social factors, such as race, education, cultural norms, and language.

- Ask your cancer care team to provide you and your loved one with cancer- and medication-related educational materials in your native language, if possible. Ask your cancer care team for a medical interpreter.

- Inequalities can be lessened, and hopefully overcome in the future; adding your voice to this conversation can empower you and honor your loved one. Your positive contribution can help underrepresented people with cancer get the best care possible.

- Connect with advocacy and support groups that include other patients who may have had experiences similar to yours and talk about any prejudices that you encounter and how to overcome them.

Spotlight on Lung Cancer

Feelings of Shame

Every year, up to 20% of people who die from lung cancer in the United States have never smoked or used any other form of tobacco.6 Their cancer was caused by something else, such as genetic changes or exposure to cancer-causing chemicals (eg, air pollution, asbestos).6 In some cases, there is no known risk factor or cause for lung cancer; it simply shows up randomly.6

For people who have a smoking history, others’ reactions to their lung cancer diagnosis may make them feel guilty, embarrassed, intimidated, and left out.7-9 They may become more withdrawn. They may share less with their healthcare providers about their ability to stop smoking, their treatment needs, and their emotional state.7 Studies show that the shame associated with smoking and lung cancer can result in a lower chance of detecting lung cancer early.10 These feelings also make it tougher for patients and their cancer care team to communicate and can delay treatment.7,9

Lung Cancer Stigma and Lack of Research Funding

Caregivers who are also lung cancer advocates shared their belief that lung cancer receives less research funding from the U.S. government compared with other types of cancer. Recent data show that although lung cancer is more common than any other type of cancer and causes 3 times as many deaths as breast cancer and colorectal cancer, it receives less funding. Whereas lung cancer accounts for 32% of cancer deaths, it receives only 10% of cancer research funding. Lung cancer advocates attribute this lack of funding to unfair stigmas surrounding the disease.Sources: Carter AJR, Nguyen CN. A comparison of cancer burden and research spending reveals discrepancies in the distribution of research funding. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:526; Bjork D. Is there a stigma in lung cancer research funding? LungCancer.net website. https://lungcancer.net/living/stigma-in-research-funding/. Published August 30, 2017. Accessed August 18, 2018

Improving Cancer Outcomes

Much Progress…

Cancer outcomes—how long and how well patients with cancer live their lives—are continually improving. Detecting cancer when it is small enough to be removed and new types of treatments have significantly reduced the burden of cancer in the United States.11 From 1990 through 2014, the cancer death rate among adults dropped 25% and the death rate among children and adolescents (aged 19 and younger) dropped 35%.11

…But a Long Way to Go

As the population ages, the number of new cancer cases and cancer deaths will continue to grow. In some types of cancer, the rates of new cases and deaths attributed to cancer are still increasing, despite improvements in diagnosis and treatment.11 The caregivers who participated in the roundtable meeting highlighted 3 specific areas of cancer care that they believe need substantial improvement: (1) biomarker testing at the time of cancer diagnosis, (2) shared decision-making (SDM) between patients and their cancer care providers, and (3) survivorship. (Survivorship, which starts at the point when cancer is diagnosed, is the idea of living with, through, and beyond cancer.12)

Testing for Cancer Biomarkers

For many types of cancer, biomarker testing (also known as genetic testing or molecular testing) is critical. The term biomarker refers to any of the body’s molecules that can be measured to assess health.13 These molecules can be obtained from blood, body fluids, or a tissue sample. Doctors use biomarker tests to identify features of a patient’s cancer that can help them choose among treatments.13

For example, more than 75% of patients with lung cancer, specifically a type known as adenocarcinoma, have genetic alterations that doctors may be able to use to help inform treatment decisions.14 The problem is that some patients are not getting tested. Data from the Lung Cancer Alliance HelpLine showed that from September 2016 through July 2017, 155 of 288 (54%) patients who called the helpline and were asked if they had received any kind of molecular testing replied “No.”15

The caregivers said that they would like to see cancer societies, pharmaceutical companies, and schools take a stronger stance when educating people about biomarker testing.

“This is why I talked to people at about 60 cancer centers during the first year. People have been aware of lung cancer for a long time because of health classes taught in schools, but they do not have the latest information. Patients and caregivers should not have to fight for genetic testing.”

—Chris Draft

Making Cancer Decisions Together

The concept of shared decision-making means that individuals with cancer (and their caregivers) make decisions about treatment together with the healthcare team. SDM is especially appropriate when there is more than one treatment to consider, and the patient’s preferences and values can help the team choose the treatment that is best for the patient.16 Studies show that SDM results in positive outcomes for people with cancer.16 However, research has also identified barriers to SDM, with some patients and their caregivers feeling a limited ability to participate.16 Cancer caregivers in the roundtable meeting reinforced how important it is for patients and caregivers to stay informed, ask questions, and share their preferences and needs.

“I learned not to lean on the doctors and let them make all the decisions. It is so important to pay attention to what they are doing. Doctors are human; they make mistakes. You need to be a part of decision-making and keep communications open.”

—Robin Youkilis DiPaolo

“We, the caregivers, need to ask questions and learn as much as we can. Chemotherapy can cause nausea, vomiting, and low blood counts, but it can also cause things like ‘chemo brain’ (thinking and memory problems caused by chemotherapy). I wish I had learned about chemo brain from the very beginning.”

—Kimberly Hall Alexander

“Second opinions [related to treatment decisions] are not a bad thing. Your doctor should not be offended if you want a second physician to look at your case. If they are offended, find a new doctor.”

—Kristine Cherol

Remember:

- Many cancer centers and oncology practices prioritize genetic and biomarker testing as recommended in national cancer care guidelines. Ask about genetic and biomarker testing as early as possible.

- Shared decision-making is an opportunity for patients and their caregivers to speak and work with their cancer care team to make treatment decisions together. Your care team members are experts in cancer treatments, but you (and the patient) are the expert when it comes to your loved one. Be sure that your voices are part of the conversation.

- Understand that the entire family changes when one of the family members has cancer, and that each person’s experience may be different. There is an opportunity to acknowledge and applaud every victory throughout the journey, whether it is groundbreaking or not. Celebrating even the smallest successes helps everyone to stay positive.

Self-Care: Caring for the Cancer Caregiver

High Stress

The physical and emotional stress associated with caring for a loved one with cancer may be a lot to handle.1 For almost all caregivers, this role is new and different. Many things about how you interact with your loved one may change. Caregivers in the roundtable shared that it is normal to feel confused, sad, guilty, angry, lonely, and stressed. Their ability to handle the tasks and pressures of their caregiver role changed from day to day, as well as over time.

“My wife was in amazing shape when she was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer. That’s when you really learn that anyone can get lung cancer. I became her caregiver, which meant I was her trainer, her equipment guy, and her cheerleader. For me, the most important thing was to always give her a visual of hope. Regardless of what was going on, she needed to see me saying, ‘Let’s go get this.’”

—Chris Draft

“This is not easy. I feel as if I live under a cloud of shoes, just waiting for one to drop.”

—Danielle Pardue

Some of the caregivers admitted that it was hard for them to hear others’ ideas about what they should do to care for themselves. This was particularly tough when they were already stressed by taking care of their loved one’s needs. If you feel this way, know you are not alone, and these feelings are very common.

“I felt overwhelmed with all of the advice: take a walk, eat well, get a good night’s rest. Sure, walking helps, but it’s not that easy. I remember being so sick of dealing with medical stuff that I [would] blow off my own medical appointments.”

—Kristine Cherol

Less Helpful “Help”

The caregivers noted that some of the support offered by friends and family was valuable, whereas other pieces of advice were not at all helpful. A few of the caregivers were able to turn the situation around to get the help they needed.

“Most people mean well, so when someone offers help that’s not helpful, flip the conversation around and ask for something that would help. If someone were to ask if the patient has tried a juicing diet, reply by asking ‘Could you bring me lunch Saturday?’”

—Danielle Pardue

“Make a list of the things that you need, such as dinner on a given day or a gas card, and then when people ask how they can help you have an answer at the ready.”

—Kristine Cherol

Finding Resources

Caregivers said they often needed help with things that were not directly related to the patient’s medical care at all. Examples are childcare, household tasks (including yardwork and home repairs), as well as finding therapists and support groups for both their children and themselves. Each of these tasks required precious time that the cancer caregivers did not have.

“Caregivers like me look for help with household maintenance, childcare, and activities for their kids. I remember looking at house cleaning services. They offered discounted cleaning services, but only if the female of the house was the patient, not for me and my husband.”

—Kristine Cherol

Some tasks were also difficult to deal with because they were new. Many of the caregivers said that it was challenging to tell an employer about their loved one’s cancer diagnosis. Most had never had to talk with insurance companies about employment benefits or understand the Family Medical Leave Act. The stress was real and continuous, and the group of caregivers retrospectively empathized with each other about how they wished they had been able to advise themselves in the past.

“Caregivers need help with tasks that have nothing to do with the patient. Most people do not know how to navigate their loved one’s employer and the Family Medical Leave Act. [How do you manage that on top] of all the other phone calls you have to make? We need so many different skills and so much knowledge at different times. The big problem is that you don’t know what you need until the very moment you need it; hindsight really is 20/20.”

—Danielle Pardue

Accepting Help

In this context, caregivers participating in the roundtable were quick to state that accepting help from others is not always easy. When tough things happen, many people tend to pull away and try to handle them on their own.1 The group agreed that it is important to be honest with yourself about tasks that you can do, tasks you can distribute to others, and tasks you can leave undone. Their suggestions included:

- You do not have to do it all; ask for help

- Be specific about what you need

- Don’t be surprised if people you thought would help do not “show up”

- Set boundaries; share details with only those people who you trust

- It is OK to be “selfish”; take at least small amounts of time for yourself.

“I don’t ask for help very well. And it didn’t always work out. I asked my family for help, and they said, ‘You can handle it; you’re superwoman.’ I lost patience with them at that point and told them they were all going to outlive my daughter. I coped by spending all of my time with [my daughter] Jill.”

—Ros Miller

“The concept of taking time for yourself is tough. But you can make the breaks bite-sized; take 5 minutes to listen to your favorite song.”

—Kristine Cherol

Remember:

- Cancer caregivers may need help throughout their own journey. Ask for help and accept help when it is offered; this is not a sign of weakness or failure.

- Other people who care about you and your loved one may not know exactly what to say, but they want to help you. Take advantage of their kindness and tell them what you need. If you feel awkward, think about how you can “pay it forward” to them or someone else in the future.

- Self-care is not selfish; taking care of yourself really does make you a better caregiver.

“After my husband passed, I went to fitness classes where no one knew me or what I had gone through. That was huge for me. With people I know, it was always, ‘I’m so sorry.’ You do not have to share your story with everyone, in person or on Facebook. You can set boundaries and be selfish sometimes. This is OK, it’s healthy.”

—Kimberly Hall Alexander

References

- National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. Caring for the Caregiver. NIH Publication No. 14-6219. www.cancer.gov/publications/patient-education/caring-for-the-caregiver.pdf. Published September 2014. Accessed August 18, 2018.

- Carter AJR, Nguyen CN. A comparison of cancer burden and research spending reveals discrepancies in the distribution of research funding. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:526.

- Bjork D. Is there a stigma in lung cancer research funding? LungCancer.net website. https://lungcancer.net/living/stigma-in-research-funding/. Published August 30, 2017. Accessed August 18, 2018.

- Ashley L, Lawrie I. Tackling inequalities in cancer care and outcomes: psychosocial mechanisms and targets for change. Psychooncology. 2016;25:1122-1126.

- Perez GK, Mutchler J, Yang MS, et al. Promoting quality care in cancer patients with limited English proficiency: perspectives of medical interpreters. Psychooncology. 2016;25:1241-1245.

- American Cancer Society. What causes non-small cell lung cancer? www.cancer.org/cancer/non-small-cell-lung-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/what-causes.html. Last revised May 16, 2016. Accessed August 18, 2018.

- Hamann HA, Ver Hoeve ES, Carter-Harris L, et al. Multilevel opportunities to address lung cancer stigma across the cancer control continuum. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:1062-1075.

- Carter-Harris L. Lung cancer stigma as a barrier to medical help-seeking behavior: practice implications. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27:240-245.

- Chambers SK, Dunn J, Occhipinti S, et al. A systematic review of the impact of stigma and nihilism on lung cancer outcomes. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:184.

- Quaife SL, Marlow LAV, McEwen A, et al. Attitudes towards lung cancer screening in socioeconomically deprived and heavy smoking communities: informing screening communication. Health Expect. 2017;20:563-573.

- National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. Annual Plan & Budget Proposal for Fiscal Year 2019. NIH Publication No. 16-7957. www.cancer.gov/about-nci/budget/plan/2019-annual-plan-budget-proposal.pdf. Published September 2017. Accessed August 19, 2018.

- Cancer.net. What is survivorship? www.cancer.net/survivorship/what-survivorship. Published May 2018. Accessed August 19, 2018.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Patient and caregiver resources: biomarker testing. www.nccn.org/patients/resources/life_with_cancer/treatment/biomarker_testing.aspx. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- Mendes E. Discovery of new lung cancer mutations may mean more treatment options. American Cancer Society website. www.cancer.org/latest-news/discovery-of-new-lung-cancer-mutations-may-mean-more-treatment-options.html. Published July 25, 2014. Accessed August 18, 2018.

- King JC, Ciupek A, Perloff T, et al. Identifying and addressing gaps in molecular testing for patients with lung cancer. Poster presented at the18th IASLC World Conference on Lung Cancer; Yokohama, Japan; October 2017. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- Butow P, Tattersall M. Shared decision making in cancer care. Clin Psychol. 2005;9:54-58.

Organizations That Provide Cancer Caregiver Resourcesa

For Any Cancer Caregivers

American Cancer Society – Hope Lodge

www.cancer.org/treatment/support-programs-and-services/patient-lodging/hope-lodge.html

American Lung Association – Inspire Lung Cancer Survivors Support Group

www.inspire.com/groups/american-lung-association-lung-cancer-survivors

Cancer and Careers

www.cancerandcareers.org

CancerCare

www.cancercare.org

Cancer Support Community

www.cancersupportcommunity.org

CaringBridge

(secure personal health journal and communication tool)

www.caringbridge.org

Foundation Medicine (molecular testing)

www.foundationmedicine.com

Global Resource for Advancing Cancer Education (GRACE)

www.cancergrace.org

International Cancer Advocacy Network (ICAN)

www.askican.org

MyLifeLine.org Cancer Foundation

www.mylifeline.org

Stupid Cancer (for young adults)

www.stupidcancer.org

Triage Cancer

www.triagecancer.org/resources

For Lung Cancer Caregivers

GO2 Foundation for Lung Cancerb

https://go2foundation.org

Lung Cancer Action Network (LungCAN)

www.lungcan.org

LUNGevity Foundationc

www.lungevity.org

aThis list is not exhaustive and only includes resources discussed during the Cancer Caregiver Roundtable. bThe Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation and the Lung Cancer Alliance have joined forces to become this foundation. cSee Highlight on LUNGevity Foundation.

Highlight on LUNGevity Foundation

Feelings of Shame

In 2001, LUNGevity Foundation was organized by 7 Chicago-based individuals who were diagnosed with lung cancer. Their vision and passion for finding a cure for the disease catapulted LUNGevity’s phenomenal growth. In less than 10 years, LUNGevity Foundation has clearly demonstrated its commitment to enhancing the quality of life and survivorship of people with lung cancer. Today, their efforts accelerate medical research regarding early detection of lung cancer; novel treatments; and community, support, and education for all those affected by the disease.

Each year, the organization holds the International Lung Cancer Survivorship Conference, a unique weekend-long event designed by and for people diagnosed with lung cancer and their caregivers. The conference is comprised of 3 simultaneous summits: the HOPE Summit for patients who are first-time attendees or want to learn the basics; the COPE Summit for caregivers; and the Survivorship Summit for advocates and lung cancer survivors who are interested in more advanced subjects.

“I attend the LUNGevity HOPE Summit every year; it is very informative about new therapies. By going to this meeting and networking, I now know more than 100 people with lung cancer.”

—Kristine Cherol

Source: LUNGevity website: www.lungevity.org/about-us/mission-vision-history, www.lungevity.org/for-patients-caregivers/support-services/survivorship-conferences/international-lung-cancer-3.

MAT-USO-NON-19-00086