Melanoma is the most serious type of skin cancer, with risk for the disease appearing to be on the rise. Historically, the outlook for patients diagnosed with stage III melanoma has been poor. In recent years, however, new therapies have changed the way in which patients with melanoma are treated. These treatments have already helped many patients to live longer lives with a reduced risk for a recurrence or return of their cancer. Because these treatments are so new, many patients may not know that they even exist, how they work, and what types of side effects they might cause. By providing information about the most recent advances in the treatment of melanoma, we hope to empower patients and their families as they navigate through their journey. It is our belief that this publication will help you to work with your healthcare team as you decide which therapies are best for you.

What Is Melanoma?

Melanoma is a type of skin cancer that begins in cells known as melanocytes. Melanocytes are specialized cells that produce the pigment (melanin) that gives our skin and hair their color. High amounts of sun exposure or exposure to other sources of ultraviolet (UV) light (such as tanning beds) can play a role in the development of melanoma. In fact, the most common form of melanoma, cutaneous melanoma, occurs in areas of the skin that have been exposed to sources of UV light. Although UV light plays a major role in the development of melanoma, patients should be aware that 3 other types of melanoma exist that are not thought to be related to UV exposure: (1) acral melanoma, which forms on the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, or under the fingernails or toenails; (2) uveal melanoma, which develops in the eyes; and (3) mucosal melanoma, which arises inside the mucous membranes of the body, such as inside the nose or the throat.

Melanoma: Risk Factors and Statistics

Skin cancer, which includes both melanoma and nonmelanoma—squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma—skin cancers, is one of the most common forms of cancer diagnosed in the United States.1 Although melanoma is the least common among all types of skin cancers, it is the most deadly.1 Melanoma of the skin accounts for about 1 in every 18 new cases of cancer in the United States, making it the fifth most commonly diagnosed form of cancer.2 Although new cases of melanoma have been increasing, in recent years, death rates from melanoma have been decreasing. This is likely due, in part, to the new treatments that are reviewed below. Nevertheless, it has been estimated that 6850 individuals in the United States will die of melanoma in 2020.2

Although anyone can develop melanoma, it is generally more common among individuals born with light skin, light-colored hair, and blue or green eyes. The American Cancer Society reports that about 1 in 38 Caucasians, 1 in 1000 African Americans, and 1 in 167 Hispanics will develop melanoma over the course of their lifetime.3 Although melanoma is evidently much less common among individuals who are born with darker skin, it is often found at later or advanced stages of disease in those persons. The type of melanoma also differs among ethnicities, with African Americans more likely to develop acral melanoma and Caucasians more likely to develop cutaneous—that is, superficial spreading—melanoma.4 Differences in the stage at diagnosis and the type of melanoma partly explain why ethnic minorities may be more likely to die of melanoma.4

Importance of Early Detection

Detecting melanoma early is key to having the best possible response to treatment. Melanomas discovered at early stages (see staging below) are highly treatable and often completely curable. This is why everyone, including those who have already had melanoma or other skin cancers, should regularly check their skin for signs of melanoma. Self-checking your entire skin surface should be performed in a place that has sufficient lighting and a mirror, in order to help you view difficult-to-see areas, such as your back or your scalp. Asking another person to help look at these difficult-to-see areas is another option. It is important for everyone, particularly those with darker skin, to examine the palms of their hands, the soles of their feet, and beneath their fingernails and toenails.

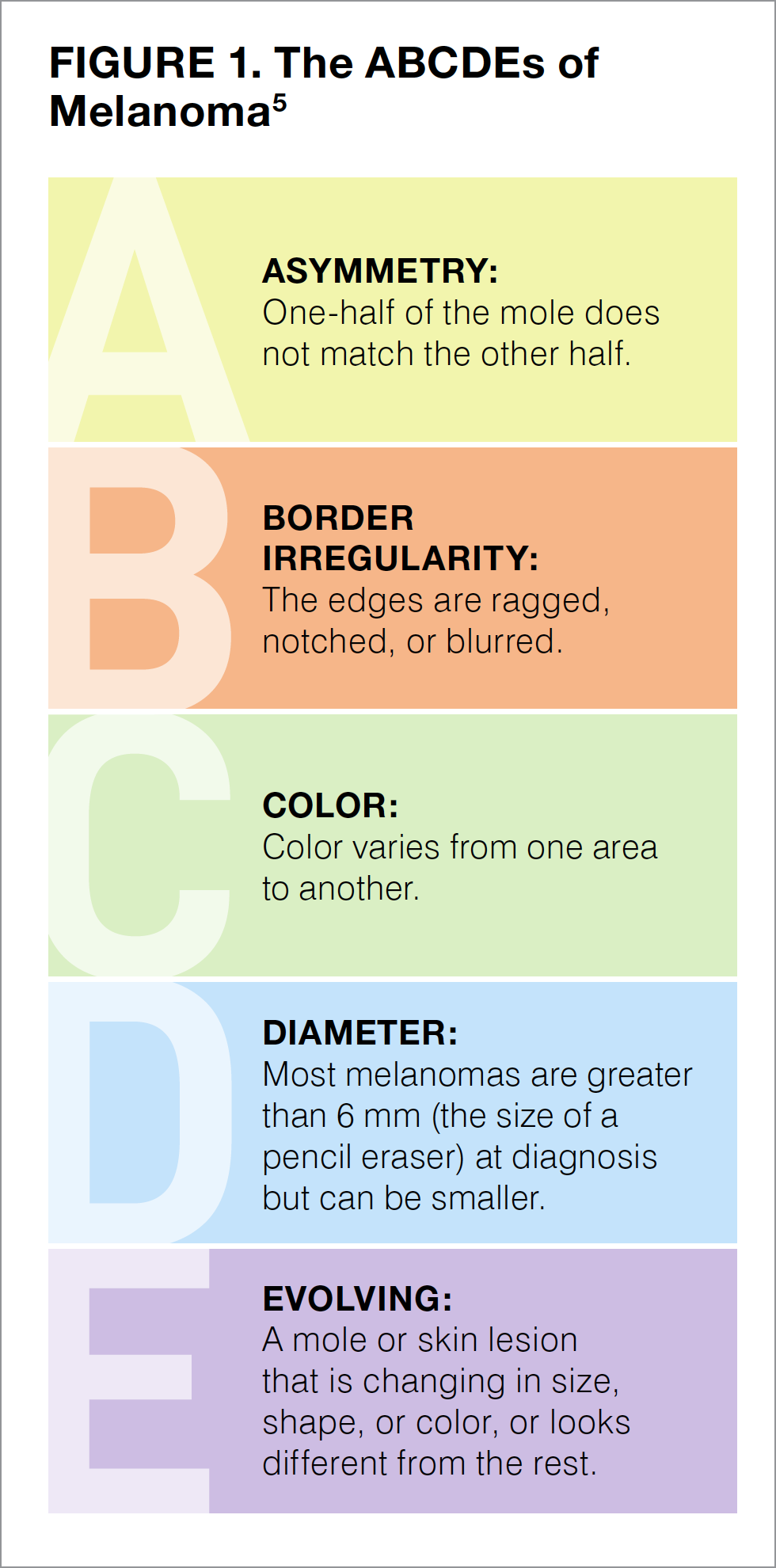

The goal of self-checking is to identify any change in a mole or a skin lesion. Figure 1 shows some of the features that you should be looking for as you examine your skin.5 Pictures can help keep track of the spots on your skin, monitor them for changes, and are useful if you need to show your physician anything that you are concerned about. If you notice a mole that looks different from the others, that is changing, that itches, or that bleeds, you should make an appointment with a dermatologist (a medical skin specialist) as soon as possible.

A physician cannot confirm melanoma just by looking at it and must take a tissue sample of the suspicious spot (that is, perform a biopsy) to make a diagnosis. Biopsy samples are sent to a dermatopathologist—a medical doctor who specializes in the diagnosis of skin disorders with the use of a microscope or laboratory tests. The 3 main types of skin biopsies are punch biopsies, shave biopsies, and excisional biopsies. In a punch biopsy, the physician uses a circular tool to remove a small section of the skin that includes both the surface and the deeper layers. Punch biopsies are commonly used only for areas that may easily scar, as they are not appropriate for identifying where the cancer ends and the healthy tissue begins (that is, the margin). In a shave biopsy, the physician removes the top layers of the skin with a small surgical blade. A deep shave biopsy, in which the physician removes the suspicious spot without penetrating the deepest layers of the skin, is the most common biopsy procedure. In an excisional biopsy, the physician uses a scalpel or surgical blade to remove the entire tumor, along with a small area or margin of normal skin around it. Excisional biopsies are generally the preferred method for suspected melanoma, although this procedure may not be possible if the area is too large, if the lesion is in a place that would result in disfigurement, or if it is located in a place on the body that could be prone to infection.

During testing of the biopsy sample, the dermatopathologist will confirm the presence of melanoma, report whether the entire cancer has been removed (that there are clear margins of normal tissue), and determine the stage of the melanoma. Based on the findings of the dermatopathologist, patients may need to undergo additional surgery to remove any remaining cancer. Patients may also need to undergo a biopsy of the lymph nodes closest to the primary melanoma (known as the sentinel lymph nodes) to determine if the cancer has spread.

For patients whose cancer has spread to the lymph nodes (stage III) or to other organs (stage IV), the dermatopathologist should also use the biopsy sample to evaluate the genes of the cancer cells (that is, perform genetic testing). Genetic testing provides important information about the biomarkers of a particular type of cancer (see below), which can be used to determine the appropriate postsurgical (or adjuvant) treatment, if needed.6-10

Biomarkers and Biomarker Testing in Melanoma

Changes to a cell’s DNA (known as genetic mutations) are part of how cancer develops. These mutations change the genes and proteins that control how a cell grows and multiplies. In recent years, researchers have discovered that some of these genes and proteins can be used as markers of how a melanoma is growing or will likely respond to treatment. Known as biomarkers, these genes and proteins are specific to the tumor itself. That means that patients do not naturally carry these mutations and thus cannot pass them onto their children. Also, because cancer biomarkers are specific to a particular type of cancer, they can differ between patients and even within multiple tumors within the same patient. That’s why biomarker testing is important—it can allow for individualized treatment.6

For patients with melanoma, the biomarkers that physicians look for include mutations in the genes BRAF (pronounced bee-raff), NRAS (pronounced en-rass), NF-1 (pronounced en-eff-1), and KIT (pronounced like the word “kit”). For patients with cutaneous melanoma, BRAF mutations have been found to be present in 35% to 56% of tumors,7,8 whereas NRAS mutations are detected in approximately 10% to 25% of these tumors,7,8 NF-1 mutations in approximately 14%,8 and KIT mutations in approximately 2% to 3%.7 Testing for these mutations, especially for a mutation called BRAF V600, is particularly important for patients with stage III or stage IV cutaneous melanoma, as therapies have been developed that specifically target these mutations.

Performing biomarker testing requires the use of a piece of cancer tissue that was collected during the biopsy. Sometimes sufficient tissue cannot be obtained, however, or a biopsy cannot be performed. In these cases, some medical clinics may be able to use a liquid biopsy, which requires only a blood sample.9 Depending on the technique that is used, biomarker testing may have different costs and turnaround times (that is, the time to receive test results).10 Although biomarker testing may require a little more time before treatment can be initiated, patients should remember that it is important for physicians to have this information available, in order to offer the best options for melanoma treatment.

For more information on biomarker testing, including what tests will be performed, how they will be conducted, and when the results will be available, patients should consult with their own healthcare team.

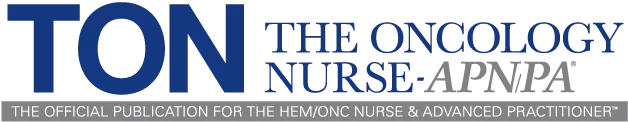

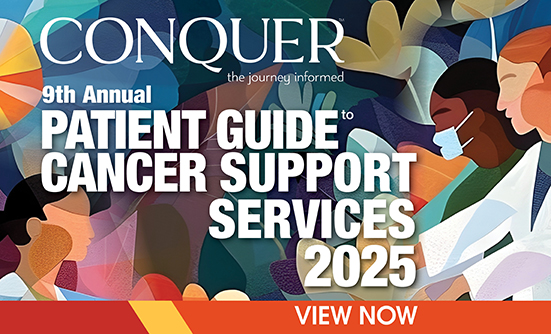

Staging and Treatment

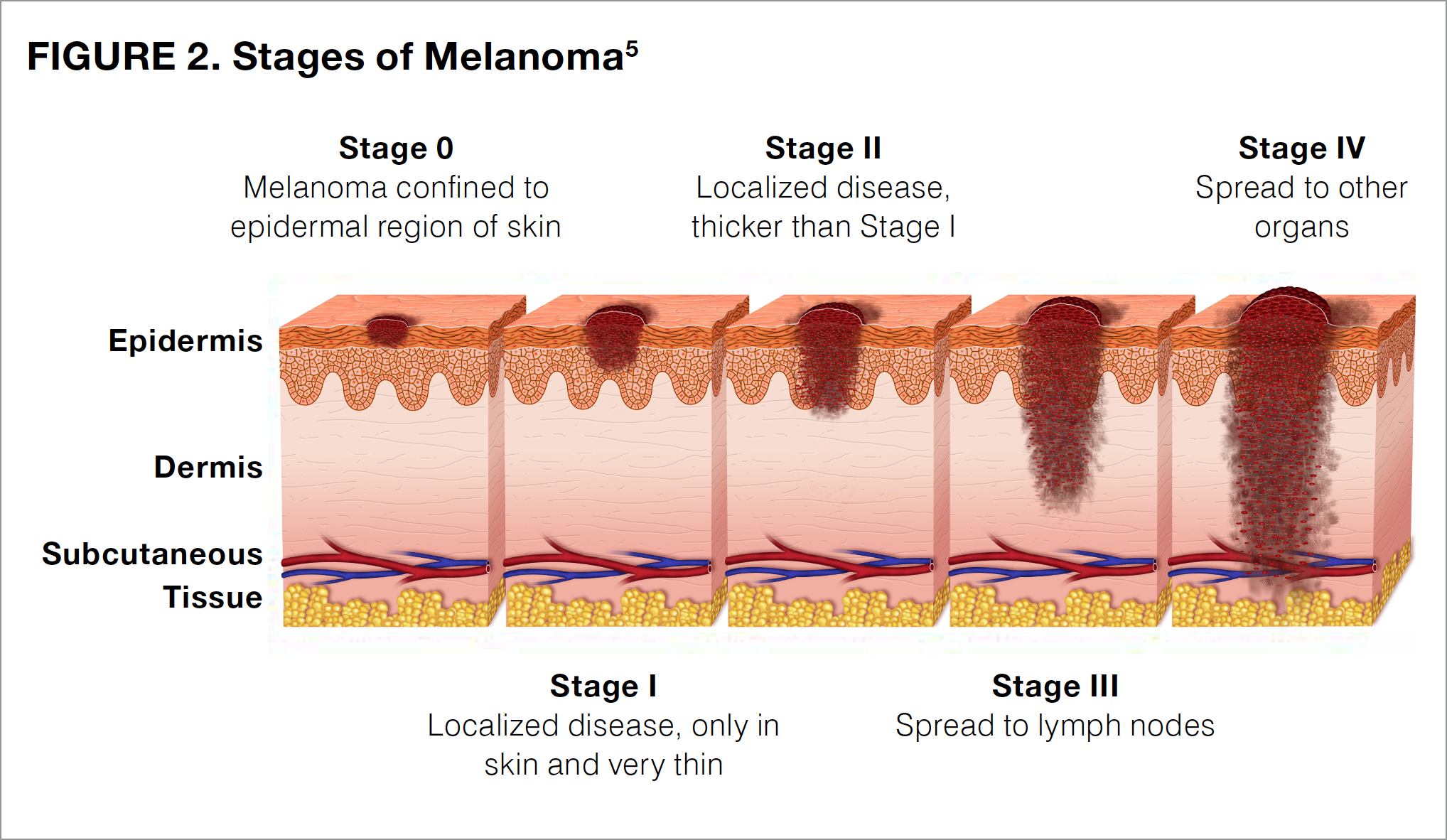

Cancer staging is a process that evaluates the amount of cancer that is present. Staging allows physicians to categorize cancers from different patients into groups that are likely to have similar features, therapeutic options, and response to treatment. Melanoma is staged by looking at the biopsy sample and reporting the depth of the tumor, whether tissue breakdown (ulceration) is present, and whether the tumor has spread to other parts of the body (metastasized). Melanoma can range from stage 0 (also known as melanoma in situ) to stage IV, with higher numbers indicating that the tumor has penetrated more deeply in the skin and spread farther in the body (see Figure 2). Some stages are further subdivided by using capital letters (A, B, C, and D), with the later letters in the alphabet representing a higher stage of cancer.

Different stages of melanoma require different treatment plans. Patients diagnosed at lower stages of disease (stage 0 [melanoma in situ] or stage I) can often be treated with surgical excision alone and are at a relatively low risk for the tumor returning (recurrence) or spreading (metastasis).11-14 For patients with stage II melanoma and some patients with stage I melanoma, physicians may additionally suggest a sentinel lymph node biopsy to determine whether the melanoma has spread to nearby or local lymph nodes, which is a characteristic of stage III tumors.14 Although individuals with stage 0, I, or II melanoma can frequently be cured with surgical excision alone, patients should continue to monitor their skin for signs of a new melanoma or recurrence of the original disease. It is recommended that patients continue to perform monthly self-exams and to have yearly, full-body skin exams performed by a trained dermatologist for the rest of their life.14 Certain patients with stage II melanoma should also receive regular follow-up from an oncologist—a physician who specializes in the treatment of cancer.

Patients with stage III melanoma have cancer that has already spread to the local lymph nodes and thus are at a higher risk for relapse (that is, recurrence) or metastases (that is, spreading of the cancer to other parts of the body).15,16 For patients with stage III melanoma, surgical excision and lymph node removal may not be sufficient to rid the body of all melanoma cells. Adjuvant treatment, which is defined as any additional treatment administered following surgery, is used to destroy any remaining cancer cells, and lower the likelihood of cancer recurrence. Adjuvant treatments for stage III melanoma will be discussed in further detail below.

Patients with stage IV melanoma have cancer that has already metastasized to other parts of the body, including the distant lymph nodes (that is, those lymph nodes that are far away from the melanoma) and other organs, including the brain, the lungs, and the liver.18 Unlike stage III disease, excision is not appropriate for most stage IV melanomas, which are often considered unresectable. Some of the adjuvant therapies used in patients with stage III melanoma may also be used in patients with stage IV melanoma.

A Closer Look at Stage III Melanoma

Although stage III melanoma can be broadly defined as melanoma that has spread to the regional lymph nodes, 4 different substages of stage III melanoma are mentioned in the AJCC 8th Edition: IIIA, IIIB, IIIC, and IIID. These substages are defined by the number of lymph nodes to which the cancer has spread, and whether this spread can be detected in a biopsy sample under a microscope (called microscopic, or clinically occult) or can be felt or seen by the naked eye (called macroscopic,` or clinically apparent).19 It is worth noting that patients should leave it to the discretion of their healthcare team to evaluate their lymph nodes, as touching the nodes too often can make them swell and thus create unnecessary anxiety.

Stage III melanoma is characterized by having a high risk for recurrence, with cancer generally recurring within 5 years of surgery.15 Recurrence is closely related to a patient’s survival rate, and within stage III melanoma, patients with stage IIID generally have the poorest outlook.20 The outlook for patients becomes increasingly better for those with stages IIIC, IIIB, and IIIA melanoma.20 It should be remembered, however, that every patient is different and the likelihood of recurrence depends on many factors.

Because of the high risk for recurrence, all patients with stage III melanoma should receive regular follow-up after their initial treatment. Table 1 shows a sample follow-up schedule.21 Patients should consult with their healthcare team about their own individualized follow-up.

Overview of Postsurgical Therapy for Patients with Stage III Melanoma

As mentioned above, adjuvant therapy is additional treatment that is provided following surgery, which is used to destroy any remaining cancer cells and reduce the likelihood that the cancer will recur. In recent years, the traditional adjuvant therapies—that is, chemotherapy and radiation therapy—have been replaced by more effective immunotherapies and targeted therapies in patients with melanoma.

Immunotherapies

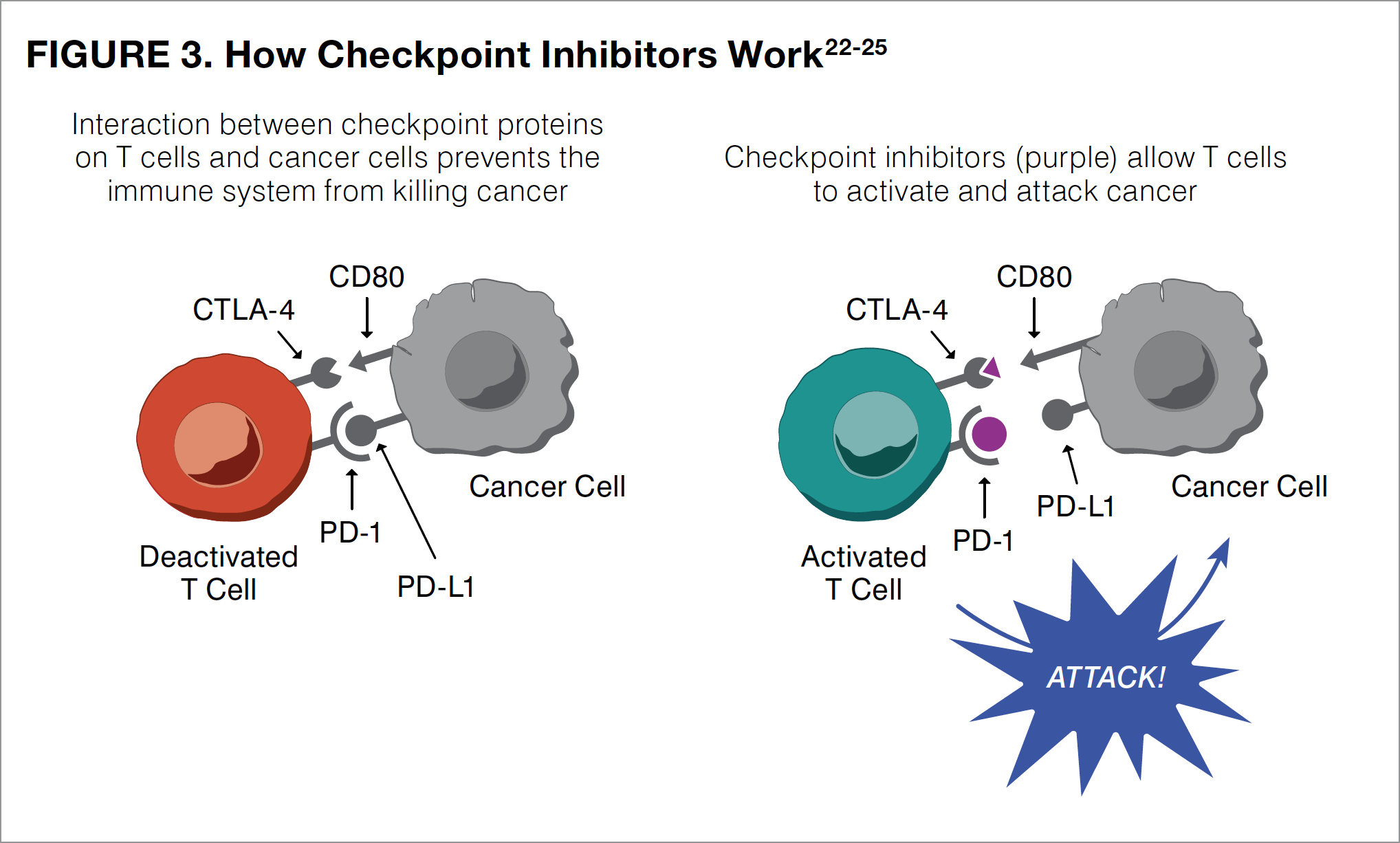

Immunotherapies increase the activity of the body’s own immune system, improving the ability to find and destroy cancer cells. The newest, most common type of immunotherapy used in patients with melanoma is called checkpoint inhibitors. Checkpoint inhibitors work by blocking a checkpoint in the immune system, thus allowing immune system T cells to better kill melanoma cells that have been left behind after surgery. The keys to turning on this immune process are the checkpoint proteins CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4), PD-1 (programmed death receptor-1), and PD-L1 (programmed death-ligand 1), with PD in the last 2 proteins an abbreviation for “programmed death.”

CTLA-4 and PD-1 are found on the T cells of the immune system, whereas PD-L1 is found on some normal cells and also can be found in high amounts on some cancer cells. When a T cell comes in contact with another cell, interactions between these checkpoint proteins act as a signal for the T cell to leave the other cell alone (see Figure 3).22-25 By blocking CTLA-4, PD-1, or PD-L1 (that is, stopping the checkpoint), T cells can learn to attack the cancer cell. Stopping the checkpoint, however, can sometimes allow T cells to also attack healthy cells. This is the cause of many side effects related to the immune system that are reported with the use of checkpoint inhibitors.

Checkpoint inhibitors that are used as adjuvant therapy in patients with melanoma include ipilimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab. All of these agents are administered as infusions that must be delivered into the bloodstream through a patient’s vein under medical supervision. Ipilimumab blocks CTLA-4 on T cells and was the first available checkpoint inhibitor to be used as adjuvant therapy in melanoma. Because ipilimumab is not as effective as the other checkpoint inhibitors and is associated with more side effects in many patients with melanoma, oncologists now mainly use nivolumab and pembrolizumab. Unlike ipilimumab, which targets CTLA-4, both nivolumab and pembrolizumab block the PD-1 protein found on immune T cells, boosting their ability to find, attack, and destroy melanoma cells (see Figure 3). These activated T cells can also attack healthy cells, resulting in side effects.14

Targeted Therapies

Targeted therapies specifically target the unique features of cancer cells, such as the genetic mutations that lead to uncontrolled cell growth (see below). As with immunotherapies, targeted therapies can be used to kill any cells that were not removed with surgery.

Changes to Melanoma Staging

Melanoma staging is based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system, which uses 3 key pieces of information to stage a cancer: the extent of the Tumor thickness (abbreviated T), whether the melanoma has spread to local lymph Nodes (N), and whether the cancer has spread to distant lymph nodes or other organs, or Metastasized (M). Combining these 3 metrics, the TNM system is then used to classify the stage of a cancer.

In 2017, with the release of the new 8th Edition staging system, the AJCC adjusted melanoma staging to incorporate additional factors that may affect a patient’s response to treatment.17 This change from the previous AJCC 7th Edition means that many melanomas have been upstaged (that is, reclassified as being at a higher stage than previously thought) or downstaged (that is, reclassified as being at a lower stage than previously thought) since the 8th Edition staging system was fully implemented in 2018.17 These changes also affect how clinical trials should be interpreted: For example, the studies presented below enrolled patients using the older AJCC 7th Edition staging system, prior to the release of the 8th Edition.

We understand that this change may be confusing for many patients and recommend that they discuss any questions about the staging of their cancer with their treatment team.

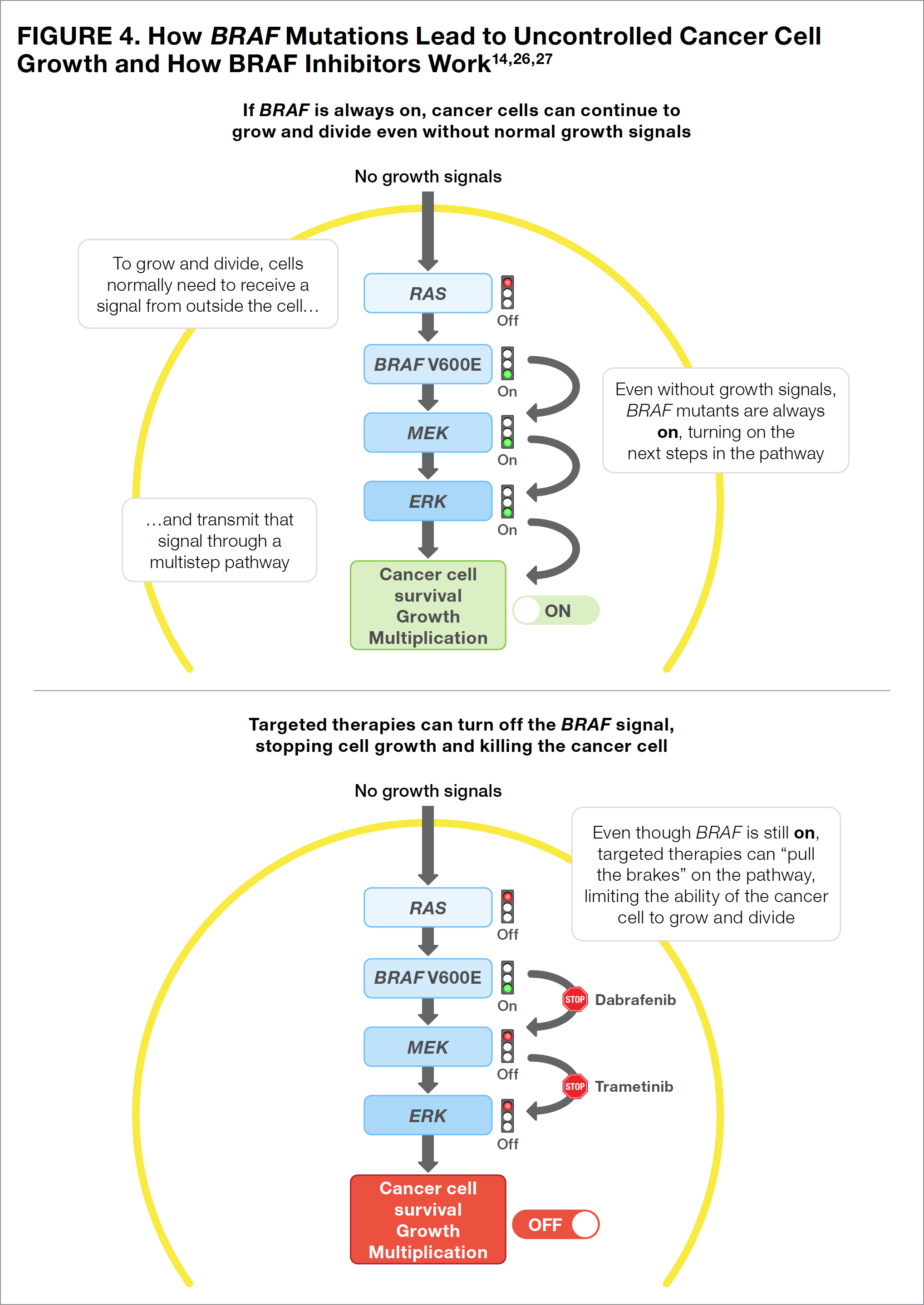

The most common mutation in melanoma, which is reported in 40% to 50% of all patients, occurs in the BRAF gene within the cancer cells.7 Patients with BRAF mutations may learn that they have either the BRAF V600E mutation or the BRAF V600K mutation. Although slightly different, both mutations produce cancer cells that cannot turn off the BRAF protein. When turned on or activated, the BRAF protein allows a cell to grow and multiply (see Figure 4). Cancer cells with a BRAF protein that is always turned “on” are able to grow and multiply out of control. By turning “off” the protein, therapies that target the BRAF mutations are able to stop their continued growth and kill the cancerous cells (see Figure 4).

The only targeted therapy that is currently available in the United States for the adjuvant treatment of melanoma is dabrafenib (a BRAF inhibitor, or a medication that stops the BRAF protein from functioning) in combination with trametinib (a MEK [mitogen-activated protein kinase] inhibitor, or a medication that stops the MEK protein from functioning).7 Using a BRAF inhibitor combined with a MEK inhibitor is more effective than a BRAF inhibitor alone and may prevent melanoma cells from becoming resistant to the BRAF inhibitor (see Figure 4).

Unlike the checkpoint inhibitors mentioned above, both dabrafenib and trametinib are taken orally. Therefore, patients are responsible for making certain that these medications are taken appropriately (see below on the importance of taking medications as prescribed).26-28 It is also important to remember that targeted therapies are only effective for patients whose cancer carries the target gene mutation (that is, dabrafenib plus trametinib should be used only for cancers with a confirmed mutation in BRAF V600). Learning the BRAF status of a cancer is the reason physicians should perform biomarker testing on biopsy samples from all patients with stage III or stage IV melanoma.7

The Importance of Taking Medications As Prescribed

To achieve an optimal response to treatment, medications need to be taken precisely according to a physician’s instructions. Immunotherapies are administered in an infusion center by a healthcare team. Targeted therapies such as BRAF and MEK inhibitors, however, are taken orally. Although oral medications are understandably preferred by patients, the absence of daily medical supervision means that the responsibility for taking these medications rests with the patient and his or her caregivers. With BRAF/MEK targeted therapies used in patients with melanoma, dabrafenib is taken twice daily, whereas trametinib is taken only once daily.26,27 Dosing calendars, pillboxes, smartphone alarms, and other types of reminders may help patients and their caregivers follow dosing schedules.

Experiencing such side effects as nausea and vomiting may make adherence to the dosing regimens of oral targeted therapy challenging, as it may be difficult for a patient to swallow the next dose of medication.28 Patients should not delay reporting any new or suspected side effect as soon as possible, so that their healthcare team can work to provide a solution. Even if certain side effects may seem minor, addressing them early on can help limit their severity before they can affect a patient’s ability to follow the treatment plan.

Evidence Supporting Postsurgical (Adjuvant) Therapies for Stage III Melanoma

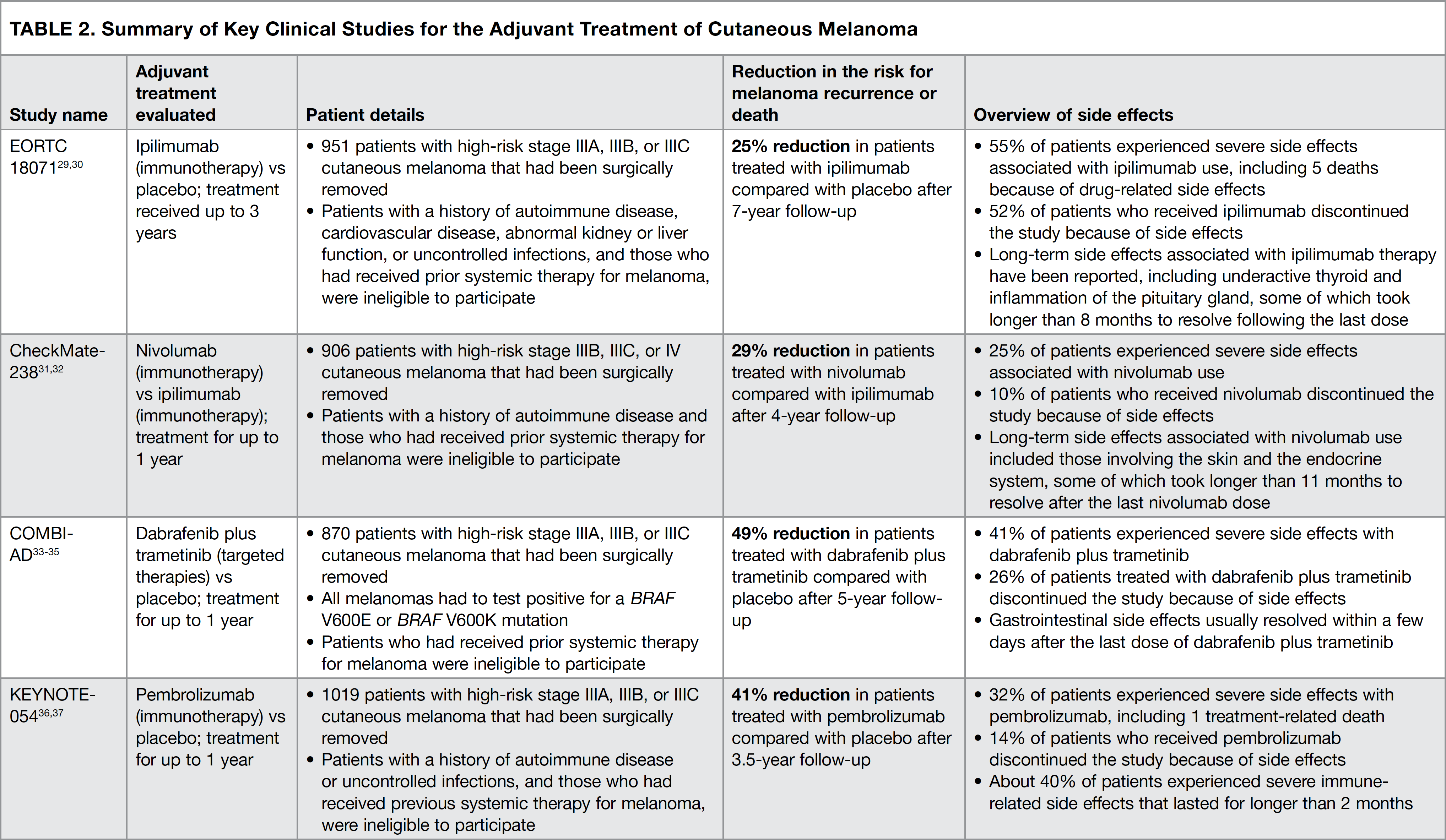

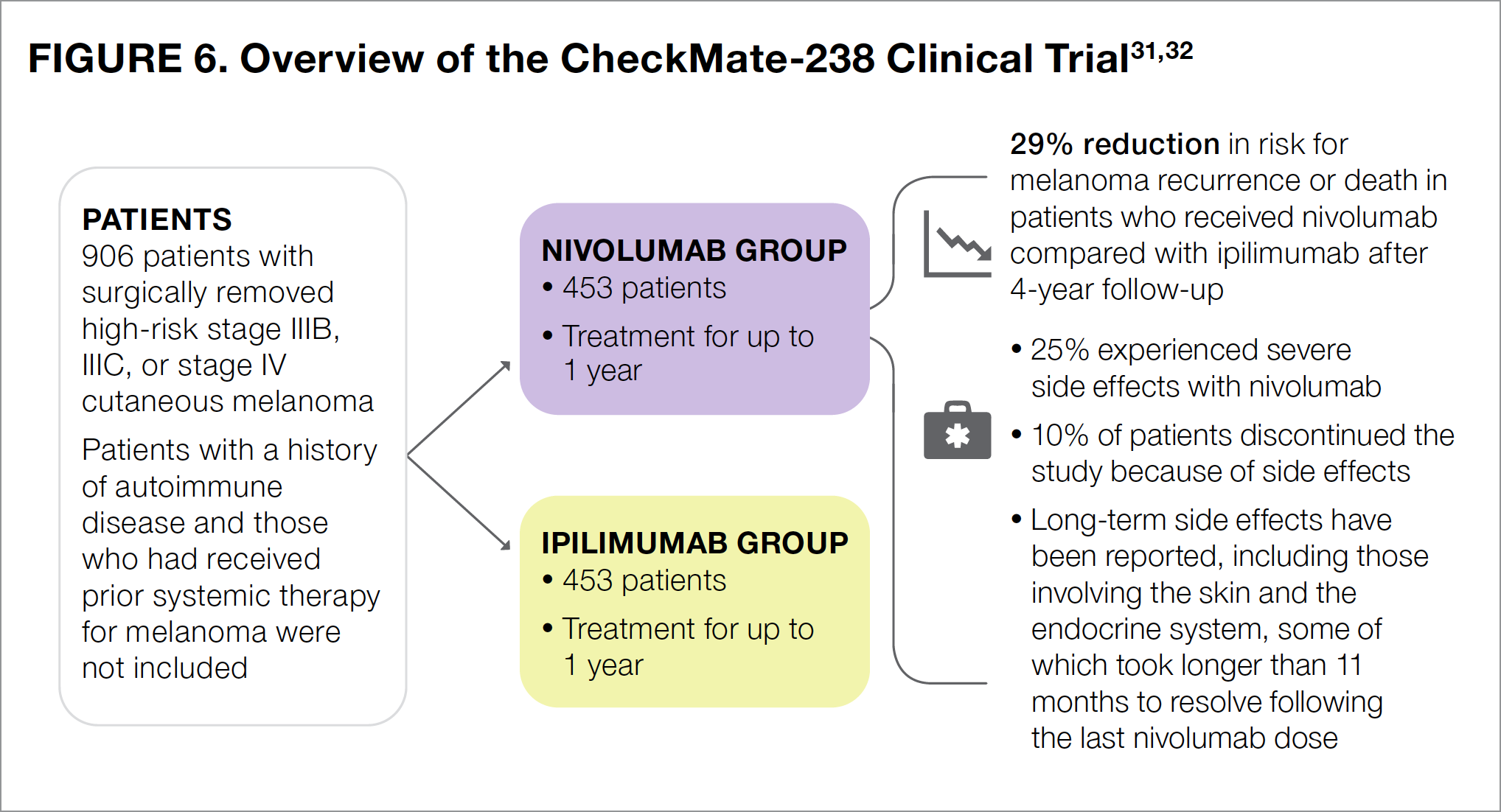

Over the past several years, the immunotherapies and targeted therapies indicated above have become available for use based on the results of clinical studies. Patients involved in these studies all had stage III melanoma that had been completely removed with surgery. The studies were carried out to determine the ability of a particular treatment to prevent the recurrence of cancer and to decrease the side effects associated with each treatment. Below, we review the details of 4 key clinical studies that have changed the ways in which patients with stage III melanoma are treated (summarized in Table 2).29-37 It is important for the reader to remember that because of the differences in how each clinical study was conducted, the results of these studies should not be directly compared with each other.

Ipilimumab versus Placebo (the EORTC 18071 Study)

The EORTC 18071 study was the first clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a checkpoint inhibitor, ipilimumab, as postsurgical adjuvant therapy in patients with high-risk stage III cutaneous melanoma. Participants in this study received infusions of either ipilimumab or placebo (an intravenously administered infusion designed to resemble the actual treatment but containing no medication) for up to 3 years (see Figure 5).29,30

Results of the study showed that 7 years after surgery, ipilimumab reduced the risk for melanoma recurrence or death by 25% (Figure 5).30 The most common side effects associated with ipilimumab included fatigue (that is, feeling tired), diarrhea, nausea, itching, rash, vomiting, headache, weight loss, fever, decreased appetite, and insomnia (that is, difficulty falling or staying asleep).22 Slightly more than half of all patients treated with ipilimumab experienced severe adverse effects, including 5 patients who died because of drug-related side effects.29 Additionally, slightly more than half of all patients (52%) in the ipilimumab group were unable to complete the study because of drug-related adverse events, with most participants withdrawing from the study within the first 3 months of treatment.29

Since immunotherapies directly affect the immune system and enhance its ability to fight cancer, many patients experience immune-related adverse events.29 For patients with immune-related side effects of the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and liver, these events generally resolve within 1 to 2 months after their last dose of ipilimumab. For patients with such adverse effects as underactive thyroid (known medically as hypothyroidism) and inflammation of the pituitary gland (known medically as hypophysitis), however, only about half had recovered by 8 months after their last dose, with the other half taking longer to experience recovery.29

Based on the results of the EORTC 18071 study, ipilimumab was the first checkpoint inhibitor available to patients for postsurgical adjuvant treatment of high-risk stage III melanoma. Because patients taking other medications have been shown to experience fewer side effects and a lower risk for melanoma recurrence, however, as described below, treatment guidelines such as those of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN; see below)38 no longer recommend ipilimumab as adjuvant therapy for patients with stage III melanoma.7

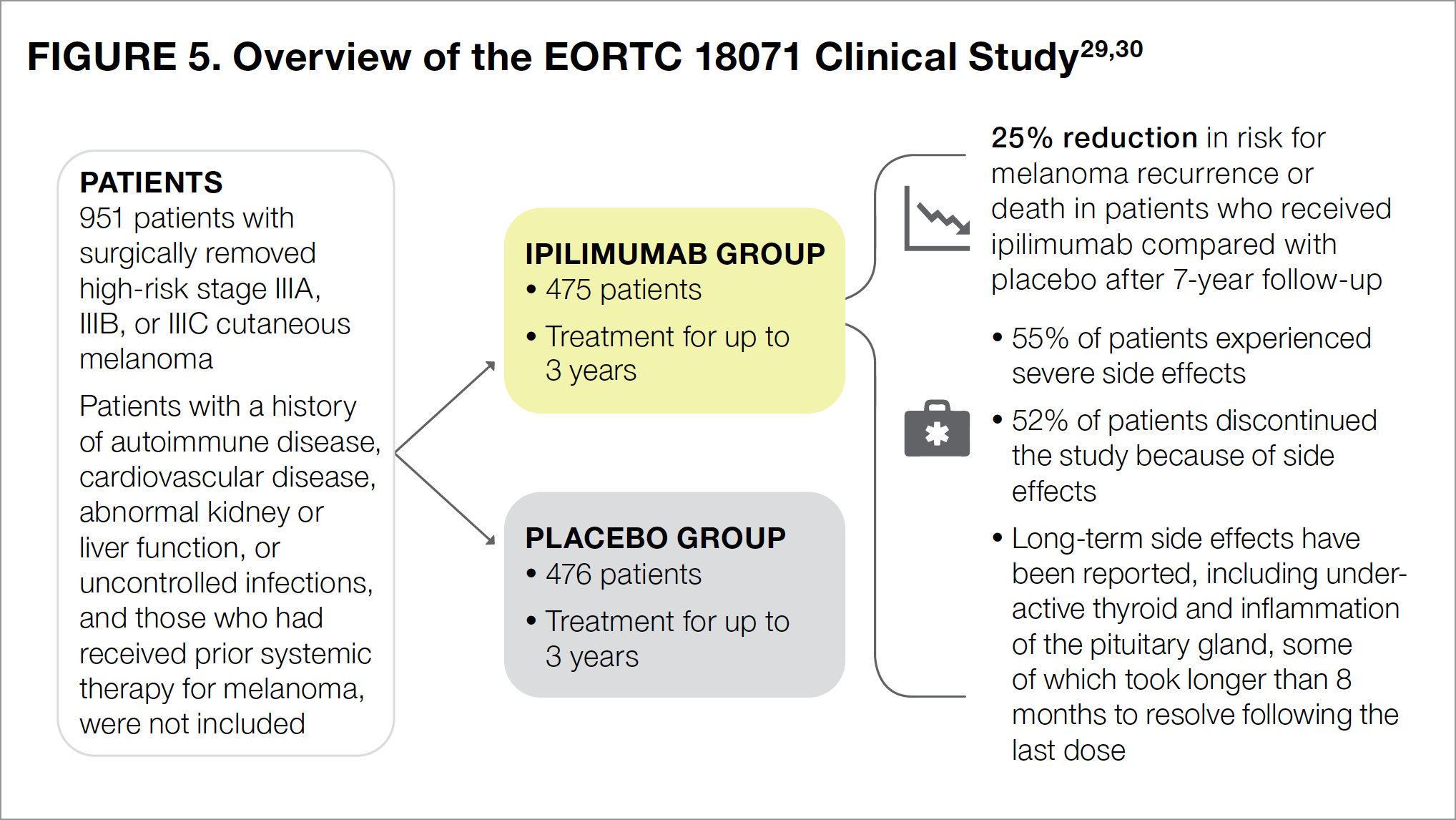

Melanoma Treatment Guidelines

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) is a not-for-profit alliance of 27 leading cancer centers, whose experts have written a set of treatment guidelines for physicians who treat melanoma.14 To create these guidelines, the NCCN Melanoma Panel evaluates all of the data that have been published from clinical trials in patients with melanoma. After reviewing the evidence from clinical trials, the NCCN provides different category levels of recommendations for each treatment. The highest recommendation the NCCN can give is Category 1, meaning that based on a high level of evidence, more than 8 of 10 panel members agree that that treatment is appropriate. Other category levels are described in Table 3 below.38

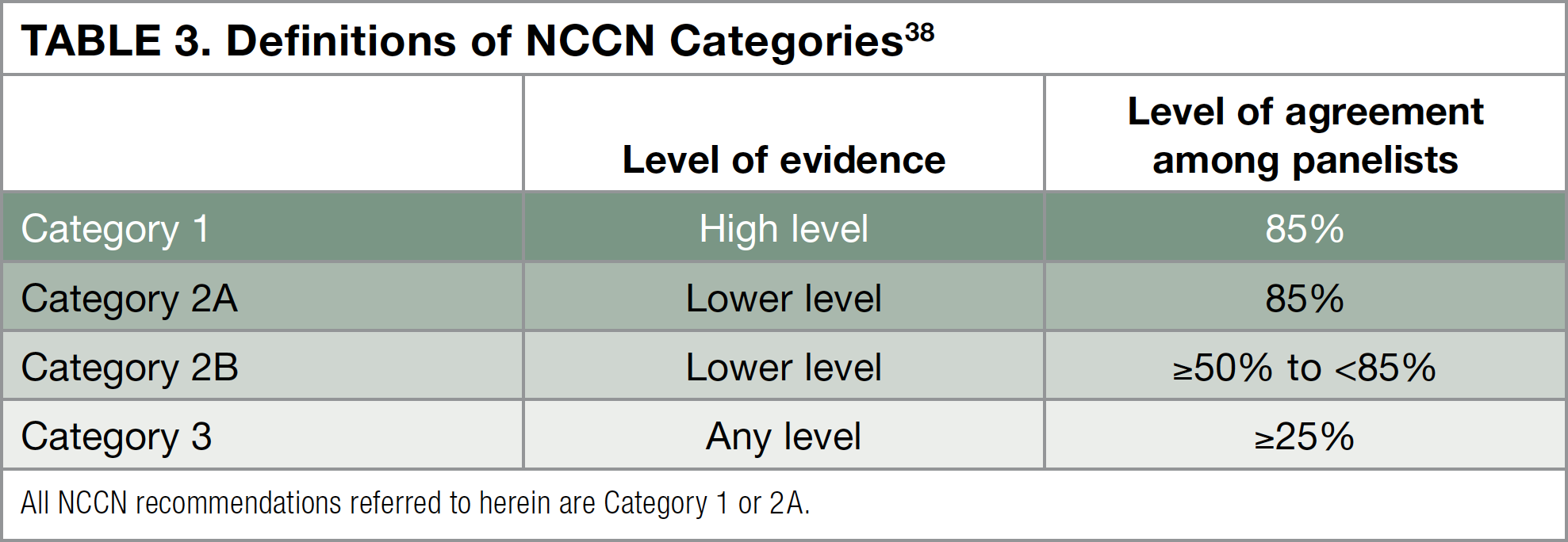

Nivolumab versus Ipilimumab (the CheckMate-238 Study)

The CheckMate-238 study was designed to compare the checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab and ipilimumab to determine which was better in preventing the recurrence of stage III or stage IV melanoma following surgery (see Figure 6).31,32 Patients were treated with either nivolumab or ipilimumab for up to 1 year.

The results of CheckMate-238 showed that 4 years after surgery, the risk for melanoma recurrence or death in nivolumab-treated patients was 29% lower than that in ipilimumab-treated patients.32 The most common side effects associated with nivolumab use were fatigue, diarrhea, rash, muscle or bone pain, itching, headache, nausea, upper respiratory infection, and abdominal pain.24

Notably, fewer patients in the nivolumab group than in the ipilimumab group reported severe side effects (25% vs 55%, respectively).31 Nivolumab was generally much better tolerated than ipilimumab. About 10% of patients in the nivolumab group discontinued the study because of intolerable side effects, compared with 43% of those in the ipilimumab group.31 Side effects associated with nivolumab use generally resolved after patients stopped taking the medication, although the time it took for the side effects to resolve varied from patient to patient, depending on the specific side effect. For patients experiencing side effects that affected the gastrointestinal tract, liver, or kidneys, half recovered within about 2 to 3 months.31 In patients with skin-related side effects, however, half still had not recovered 5 months after their last dose.31 Side effects such as underactive thyroid or inflammation of the pituitary gland lasted much longer. For patients who experienced these adverse events, half still had not recovered 11 months after their last dose of nivolumab.31 Regardless of the type of side effect, in some patients, it took longer than 1 year to fully recover.31

Based on the results of CheckMate-238, NCCN guidelines list nivolumab as a recommended adjuvant postsurgical treatment option for patients who are first diagnosed with stage III-IV melanoma that can be treated by surgery, as well as for those with recurrent stage III-IV disease.7

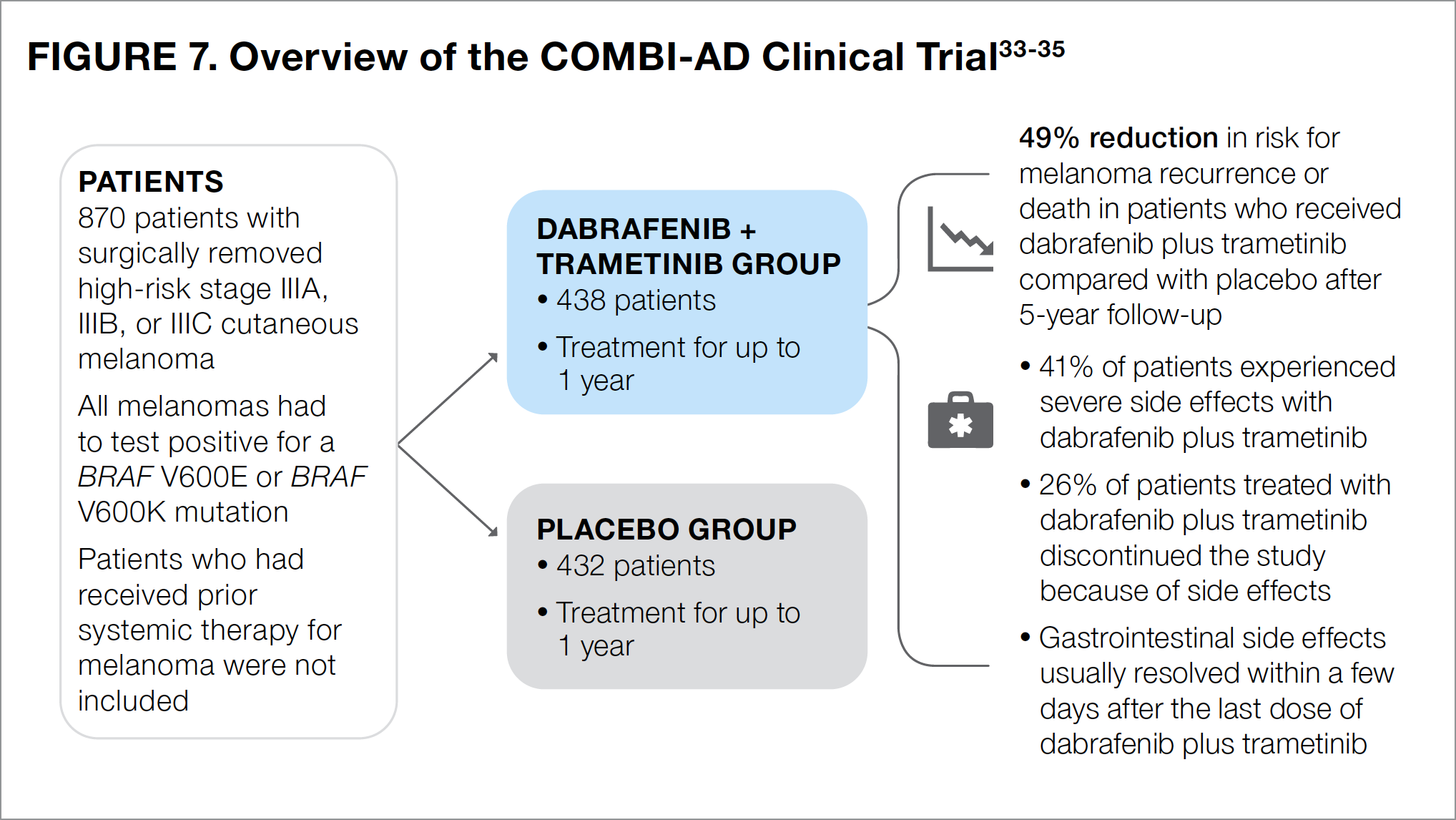

Dabrafenib plus Trametinib versus Placebo (COMBI-AD)

The COMBI-AD study compared the targeted therapies dabrafenib (a BRAF inhibitor) plus trametinib (a MEK inhibitor) with placebo as adjuvant therapy following surgery in patients with high-risk stage III melanoma (see Figure 7).33-35 Importantly, in addition to having stage III melanoma, patients in the COMBI-AD study needed to have melanoma with a BRAF V600E or a BRAF V600K mutation. Patients then received adjuvant treatment with dabrafenib and trametinib, or placebo for up to 1 year.33

At 5 years after surgery, the risk for recurrence or death in patients treated with dabrafenib plus trametinib was 49% lower than that in patients who received placebo.34 The most common side effects associated with dabrafenib plus trametinib treatment included fever, fatigue, nausea, headache, rash, chills, diarrhea, vomiting, joint pain, and muscle pain.26

About 4 in 10 patients (41%) who were treated with dabrafenib plus trametinib reported experiencing severe side effects—most commonly fever and fatigue.33 About 26% of patients who received dabrafenib plus trametinib withdrew from the study because of side effects.33 Unlike the immunotherapies previously mentioned, the side effects experienced by patients in the dabrafenib-plus-trametinib group generally resolved after the last dose of medication.35

Based on the results of COMBI-AD, adjuvant therapy with the combination of dabrafenib plus trametinib is an option recommended by the NCCN for patients with surgically removed high-risk stage III or recurrent melanoma that has a BRAF V600 mutation.7

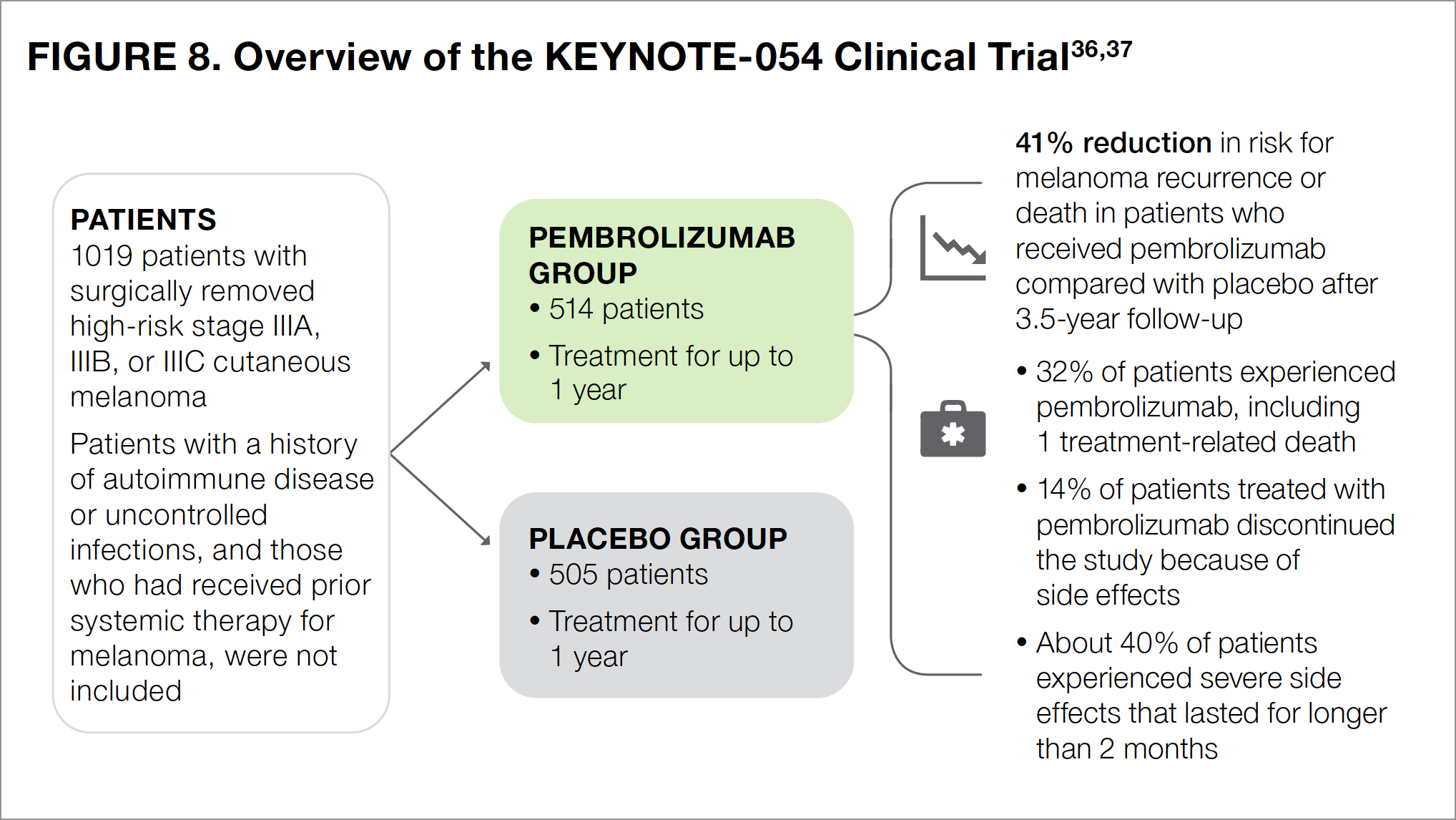

Pembrolizumab versus Placebo (the KEYNOTE-054 Study)

The KEYNOTE-054 study compared the checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab with placebo as adjuvant therapy in patients with high-risk stage III melanoma that had been completely removed by surgery (see Figure 8).36,37 All participants received pembrolizumab or placebo intravenous infusions for up to 1 year.

At 3.5 years after surgery, the risk for recurrence or death was 41% lower in the pembrolizumab group compared with the placebo group.37 The most common side effects in patients who received pembrolizumab included diarrhea, itching, nausea, joint pain, thyroid disorders, cough, rash, weakness, and weight loss.23

Approximately one-third (32%) of patients treated with pembrolizumab reported severe side effects, including 1 patient who died because of a drug-related side effect.36 About 14% of patients had to discontinue pembrolizumab therapy because they experienced 1 or more side effects.36 Similar to the other checkpoint inhibitors discussed earlier, pembrolizumab was associated with a number of immune-related side effects, which were reported in about 37% of treated patients and were most commonly thyroid disorders.36 About 7% of immune-related adverse effects were severe, half of which lasted for longer than 2 months following the last dose of pembrolizumab.36

Based on the results of the KEYNOTE-054 trial, the NCCN recommends pembrolizumab as an adjuvant therapeutic option following surgery in patients with high-risk stage III melanoma, either at presentation or at disease recurrence.7

Putting the Results of These Clinical Trials into Context

The clinical studies described above have shown that both immunotherapies and targeted therapies are adjuvant treatment options following surgery, which are intended to delay or prevent the recurrence of melanoma in patients with high-risk stage III (and stage IV) disease. Although both types of therapy provide good options for individuals with late-stage melanoma, patients should be aware of the clear differences in the side effect profiles of immunotherapies and targeted therapies.39

About 1 in 4 patients who received the checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab and about 1 in 3 patients who received the checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab in the clinical trials described above have reported experiencing severe side effects.31,36 Immune-related severe side effects that were observed in the clinical trials, such as the onset of type 1 diabetes or disorders of the thyroid and pituitary gland, have been confirmed in the treatment of real-world patients (that is, those who are not enrolled in clinical studies).

These side effects are of special concern to healthcare professionals, because they can be life-threatening and persist long after the patient has received his or her last dose of medication.40,41 An analysis of approximately 7500 patients who were treated with checkpoint inhibitors for any type of solid cancer, not just for melanoma, has shown that thyroid disorders are one of the most common adverse effects associated with the use of these medications.40 Compared with thyroid dysfunction, pituitary disorders are much less common with the use of current immunotherapies (although they were higher with ipilimumab). Despite occurring in fewer than 1 in 100 patients who received the checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab or pembrolizumab, pituitary disorders can result in a variety of hormonal changes that are often permanent and can be life-threatening if left untreated.41 As noted previously, patients should not delay in reporting any potential side effects to their healthcare team, as it may be possible to limit how severe these effects may be and how long they may last.

Because they work differently, targeted therapies do not carry the risk of triggering immune-related adverse effects. Nevertheless, about 2 of every 5 patients who received dabrafenib plus trametinib in the COMBI-AD study reported experiencing severe side effects.33 The proportion of patients treated with dabrafenib plus trametinib who withdrew from the study early because of side effects was 26%.33

One important difference between immunotherapies and targeted therapies, however, is that side effects associated with the use of targeted therapies usually resolve after treatment is stopped. Furthermore, some patients have been successful in limiting the severity of their side effects by taking such anti-inflammatory drugs as aspirin or ibuprofen before initiating targeted therapy. Again, patients should consult with their healthcare team about additional ways in which to limit potential side effects.

Although the clinical studies summarized above have led to the recommendation of nivolumab, dabrafenib plus trametinib, and pembrolizumab by clinical guidelines such as those of the NCCN, it is important to remember that each patient is unique and that the recommendations listed above may not be right for you. In particular, it is worth noting that clinical studies on immunotherapies did not include patients with a history of autoimmune diseases or uncontrolled infections, and none of the studies listed here enrolled patients who had received prior systemic therapy for melanoma.29,31,33,36 Therefore, physicians have limited understanding of how these treatments will work in those types of patients. Based on your own individual health and other factors, your physicians may recommend that you undergo other tests or treatments beyond those that have been listed here.

Final Thoughts on the Patient Journey

Based on the stage, cancer type, and other characteristics, every patient with melanoma is different. Even patients with stage III melanoma cannot be considered identical because of differences in their individual cancers (for example, where the melanoma has metastasized, and which biomarkers are present).

Despite these differences, treatments are available for almost all patients. These include new postsurgical adjuvant treatment options that have become available over the past several years and have changed the outlook for many patients with stage III melanoma. Because these options differ with respect to how they work and their potential side effects, it is important for patients to discuss with their healthcare team all of the available treatment options. As part of this discussion, patients should consider asking their healthcare team about additional biomarker testing, which is required to determine if targeted treatments are appropriate. When targeted therapies are appropriate, both patients and their caregivers have a role to play in ensuring that the medications are taken at the correct dose and at the correct time.

Regardless of which type of therapy they receive for their melanoma, all patients should discuss the development of any adverse effects with their healthcare team. Oftentimes, side effects can be effectively managed before they become serious and impact a patient’s ability to continue his or her treatment.

Recommended Melanoma Websites

Patients have many available options when it comes to seeking more information about their disease. Your healthcare team can help refer you to a number of websites, books, and pamphlets. Below, we have compiled a list of reliable, trustworthy websites that can be used to learn more about all aspects of melanoma.

- www.cancer.net – The American Society of Clinical Oncology provides education and resources for individuals living with cancer, including those with melanoma.

- https://medlineplus.gov/melanoma.html – The US National Library of Medicine provides up-to-date, science-based information in English and Spanish, along with links to other sites.

- www.cancer.gov – The National Cancer Institute (NCI) conducts and supports cancer research and training. Use this site to find patient and caregiver resources, as well as links to NCI-supported clinical trials.

- www.patientadvocate.org – The mission of the Patient Advocate Foundation is to provide “case management services and financial aid to Americans with chronic, life-threatening and debilitating illnesses.” Begin here when you need financial assistance.

- www.cancercare.org – CancerCare provides free emotional and practical support for people with cancer and their caregivers. Oncology social workers offer individual and group support (by phone, online, or in person in New York and New Jersey) in English and Spanish. Financial assistance is also available.

- www.aad.org/public – The American Academy of Dermatology/American Academy of Dermatology Association provides free educational handouts, videos, and other information on skin cancer screening, detection, and intervention.

- www.aimatmelanoma.org – The AIM at Melanoma Foundation is an advocacy organization that offers a peer connect program and toll-free phone number to speak with a healthcare professional about melanoma diagnosis and treatment. An educational video library and patient resource list provide information on reducing your risk for, being diagnosed with, and living with melanoma.

- https://melanomainternational.org – The Melanoma International Foundation is an advocacy organization that provides one-on-one support through e-mail and open discussion forums. The site delivers information “to develop personalized strategies with patients so they may live longer, better lives.”

- https://melanoma.org – The Melanoma Research Foundation supports research, provides information, and advocates for patients with the disease. The organization has resources for pediatric and young adult melanoma survivors, as well as for people with less common types of melanoma (ocular, mucosal).

- www.ocularmelanoma.org – The Ocular Melanoma Foundation focuses on ocular melanoma and provides financial assistance for travel and prosthetics to qualifying patients with the disease. A patient forum and support events are also available.

- www.curemelanoma.org – The Melanoma Research Alliance (MRA) is the largest nonprofit funder of melanoma research. The MRA funds projects in the areas of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, and hosts the Melanoma > Exchange—a free online melanoma treatment and research-focused discussion group and support community.

- www.cancer.org – The American Cancer Society invests in cancer research, promotes policy changes, and also offers educational resources and support to patients living with cancer, including those with melanoma.

- www.mayoclinic.org – The Mayo Clinic is one of the largest health systems in the United States and consistently is rated near the top of hospital rankings. Use this site to find a specialist in treating melanoma or to obtain information on symptoms, diagnosis, treatments, and accessing clinical trials.

References

- National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Skin Cancer (Including Melanoma)—Patient Version. www.cancer.gov/types/skin. Accessed November 9, 2020.

- National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Melanoma of the Skin. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html. Accessed November 9, 2020.

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Melanoma Skin Cancer. www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed July 2, 2020.

- Mahendraraj K, Sidhu K, Lau CSM, McRoy GJ, Chamberlain RS, Smith FO. Malignant melanoma in African–Americans: a population-based clinical outcomes study involving 1106 African American patients form the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Database (1988-2011). Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6258.

- Vohra NA, Koutlas JB, Poole CM. Know Your Melanoma. CONQUER. February 2020;(suppl):1-20.

- Caris Life Sciences. What are biomarkers? The growing importance of biomarkers in cancer. www.mycancer.com/resources/what-are-biomarkers. Accessed July 21, 2020.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Cutaneous Melanoma. Version 4.2020 — September 1, 2020. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cutaneous_melanoma.pdf Published May 18, 2020. Accessed June 10, 2020.

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell. 2015;161:1681-1696. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044.

- Gaiser MR, von Bubnoff N, Gebhardt C, Utikal JS. Liquid biopsy to monitor melanoma patients. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:405-414.

- Bisschop C, ter Elst A, Bosman LJ, et al. Rapid BRAF mutation tests in patients with advanced melanoma: comparison of immunohistochemistry Droplet Digital PCR, and the Idylla Mutation Platform. Melanoma Res. 2018;28:96-104.

- Melanoma Research Alliance. Stage 0 Melanoma. www.curemelanoma.org/about-melanoma/melanoma-staging/stage-0. Accessed December 2, 2020.

- Melanoma Research Alliance. Stage 1 Melanoma. www.curemelanoma.org/about-melanoma/melanoma-staging/stage-1. Accessed December 2, 2020.

- Melanoma Research Alliance. Stage 2 Melanoma. www.curemelanoma.org/about-melanoma/melanoma-staging/stage-2. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN GUIDELINES FOR PATIENTS: Melanoma. Published 2018. www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/melanoma-patient.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- Romano E, Scordo M, Dusza SW, Coit DG, Chapman PB. Site and timing of first relapse in stage III melanoma patients: implications for follow-up guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3042-3047.

- Melanoma Research Alliance. Stage 3 Melanoma. www.curemelanoma.org/about-melanoma/melanoma-staging/stage-3. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- Ferguson PM, Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA. Staging of cutaneous melanoma: is there room for further improvement? JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e180086.

- Melanoma Research Alliance. Stage 4 Melanoma. www.curemelanoma.org/about-melanoma/melanoma-staging/stage-4. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- AIM at Melanoma Foundation. Stage III Melanoma. Published 2014. Accessed November 10, 2020. www.aimatmelanoma.org/stages-of-melanoma/stage-iii-melanoma. Accessed July 21, 2020.

- Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:472-492.

- AIM at Melanoma Foundation. Follow Up by Stage. www.aimatmelanoma.org/after-treatment/follow-up-by-stage. Accessed December 2, 2020.

- YERVOY (package insert). Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2020. https://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_yervoy.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- KEYTRUDA (package insert). Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co., Inc.; 2020. www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/k/keytruda/keytruda_pi.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- OPDIVO (package insert). Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2020. https://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_opdivo.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- American Cancer Society. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Their Side Effects. Published December 27, 2019. www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/treatment-types/immunotherapy/immune-checkpoint-inhibitors.html. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- TAFINLAR (package insert). East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2020. www.novartis.us/sites/www.novartis.us/files/tafinlar.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- Khunger A, Khunger M, Velcheti V. Dabrafenib in combination with trametinib in the treatment of patients with BRAF V600-positive advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: clinical evidence and experience. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2018;12:1753466618767611.

- Kottschade LA, Lehner Reed M. Promoting oral therapy adherence: consensus statements from the Faculty of the Melanoma Nursing Initiative on oral melanoma therapies. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21(4 suppl):87-96.

- Eggermont AMM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob J-J, et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage III melanoma (EORTC 18071): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:522-530.

- Eggermont AMM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob J-J, et al. Ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of stage III melanoma: long-term follow-up results the EORTC 18071 double-blind phase 3 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15 suppl):2512-2512.

- Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, et al. CheckMate 238 Collaborators. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1824-1835.

- Weber J, Del Vecchio M, Mandala M, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab (NIVO) vs ipilimumab (IPI) in resected stage III/IV melanoma: 4-year recurrence-free and overall survival (OS) results from CheckMate 238. Presented at: European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Virtual Congress 2020 Online Programme; November 20-22, 2020. Abstract 1076O.

- Long GV, Hauschild A, Santinami M, et al. Adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage III BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1813-1823.

- Hauschild A, Dummer R, Santinami M, et al. Long-term benefit of adjuvant dabrafenib + trametinib (D+T) in patients (pts) with resected stage III BRAF V600–mutant melanoma: five-year analysis of COMBI-AD. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15 suppl):10001-10001.

- Heinzerling L, Eigentler TK, Fluck M, et al. Tolerability of BRAF/MEK inhibitor combinations: adverse event evaluation and management. ESMO Open. 2019;4:e000491.

- Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1789-1801.

- Eggermont AM. Pembrolizumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage III melanoma: Final results regarding metastasis-free survival results from the EORTC 1325-MG/Keynote 054 double-blinded phase III trial. Presented at: European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Virtual Congress 2020 Online Programme; November 20-22, 2020. Abstract LBA46.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Development and Update of the NCCN Guidelines®. www.nccn.org/professionals/development.aspx. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- Garbe C, Amaral T, Peris K, et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for melanoma. Part 2: Treatment — Update 2019. Eur J Cancer. 2020;126:159-177.

- Barroso-Sousa R, Barry WT, Garrido-Castro AC, et al. Incidence of endocrine dysfunction following the use of different immune checkpoint inhibitor regimens. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:173-182.

- Girotra M, Hansen A, Farooki A, et al. The current understanding of the endocrine effects from immune checkpoint inhibitors and recommendations for management. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018;2:pky021.