Several recent studies focused on racial disparities in the treatment of black (or African-American) men and white men (of European ancestry) who are diagnosed with prostate cancer, in the search for the reasons for those disparities and how to address them. These studies were highlighted in a special session during the 2021 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Peter C. Black, MD, FRCSC, Chair, Vancouver Prostate Centre, Department of Urologic Sciences, University of British Columbia, Canada, provided commentary on each of these studies, highlighting the disparities in prostate cancer care in the United States, which underscore the importance of prostate cancer screening, genomic testing, and personalized medicine in black men to reduce the gap between men of different racial or ethnic backgrounds and reduce the high mortality rate of black men from this disease.

Difference in Prostate Cancer Screening

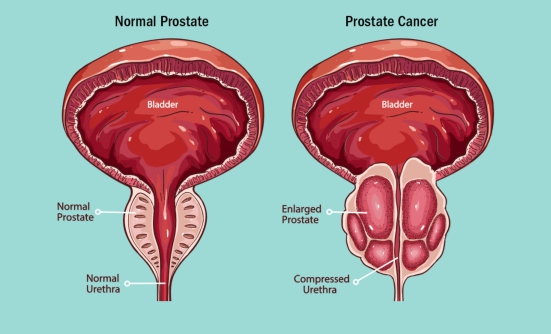

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening is an important tool for the diagnosis of prostate cancer, particularly in black men, according to results of an analysis of 4,700 men diagnosed with prostate cancer at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) over 13 years.

The study showed that men with a low PSA screening score before prostate cancer diagnosis were more likely to have less advanced prostate cancer at diagnosis. By contrast, men with a PSA score of more than 20 were more likely to have advanced or metastatic (stage IV) prostate cancer at the time of diagnosis.

According to Dr. Black, African-American men are at an increased risk of prostate cancer, which also occurs at a younger age than in white men. Previous research has also shown that they have less access to PSA screening than white men.

In this study from the VA, “Both PSA screening rate and the visit rate to the primary care provider predicted the disease severity,” said Dr. Black. “Lower rate of screening prior to diagnosis was also correlated with prostate cancer–specific mortality.”

He emphasized the importance of early PSA screening in black men. “The results of this study demonstrate that African-American men diagnosed with prostate cancer between the age of 40 and 55 will have worse outcomes if there’s a lower rate of screening prior to diagnosis,” Dr. Black said. “These data encourage a screening policy that starts at 40 in African-American men.”

Genomic Testing Differences

A study by Kosj Yamoah, MD, PhD, Director of Radiation Oncology Cancer Health Disparities Research at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute in Tampa, Florida, and colleagues focused on genomic (or genetic) testing and its role in classifying prostate cancer as low risk or high risk, and the link to treatment decisions and ultimately, patient outcomes.

“Genomic risk stratification should happen independent of risk for localized disease—and independent of race,” said Dr. Black.

Dr. Yamoah and colleagues investigated the implementation of genomic or genetic testing in more than 100 African-American men with low- to intermediate-risk prostate cancer. The patients had genetic testing and were then treated with radical prostatectomy (surgical removal of the prostate gland) or with radiation.

The study results showed that the genomic testing was instrumental in predicting disease severity and the risk of cancer progression to metastatic prostate cancer or death, but this tool was underutilized in black men compared with white men.

“The main finding is that the African-American men are more likely to be reclassified to high genomic risk,” said Dr. Black. “The genomic classifier outperforms clinical risk stratification tools in African-American men and should be used independent of race.”

The investigators concluded that all black men with prostate cancer should undergo genomic testing, regardless of the clinical features of their disease.

Genetic Alterations

Finally, a large study investigating the role of genetic mutations or other alterations in prostate cancer showed that biological differences are unlikely to be a major cause of disparities in patient outcomes seen between black and white men diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer.

The study also showed that black men were less likely to receive comprehensive genomic profiling early in their treatment course (which can point to best treatments), and less likely to receive treatment in clinical trials compared with white men. These differences in the early treatment of prostate cancer may explain the differences in outcomes between African-American and white men.

“Ultimately, equitable use of comprehensive genomic profile testing, clinical trial enrollment, and subsequent precision medicine treatment pathways can lead to a major reduction in disparities,” said Brandon A. Mahal, MD, Assistant Professor of Radiation Oncology, University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, Florida.

According to Dr. Mahal, the number of men who are diagnosed with, and die from, prostate cancer varies widely by ethnicity or race, and African-American men have the greatest burden of prostate cancer.

“These differences are likely due to the interplay of socioeconomic factors, environmental exposures, and biological or epigenetic phenomenon,” Dr. Mahal said.

“Furthermore, precision oncology studies have underrepresented men of African ancestry, thereby limiting our comprehensive understanding of prostate cancer disparities, which can potentially lead to greater disparities,” he suggested.

The study included nearly 12,000 men with advanced prostate cancer who had comprehensive genetic profiling as part of their treatment plan; of these patients, 12% were black. Dr. Mahal and colleagues investigated the genomic landscape and the treatment patterns, according to ethnicity and racial ancestry.

Analysis of the genetic mutations demonstrated differences across ethnic groups, Dr. Mahal said. Among black men with prostate cancer, the frequency of certain genomic alterations was reduced compared with white men, including TP53, PTEN, and TMPRSS22-ERG mutations.

By contrast, genomic alterations such as MEK, SPOP, CDK12, KMT2D, CCND1, and HGF were more common in African-American men than in white men.

However, the researchers found no significant differences in the actionable genes that can be targeted by current therapies, Dr. Mahal said.

“Men of African and European ancestry showed similar patterns of targetable gene alterations, except for BRAF, which was enriched in individuals with African ancestry,” said Dr. Mahal. He added that a previous small study showed similar results in African-American men with prostate cancer.

Discussing these results, Dr. Black said that genes such as SPOP or TMPRSS22-ERG represented early DNA changes and are not affected by treatment. By contrast, TP53 and TPEN are genetic alterations that are likely to be affected by treatment, and they are less common in black men with prostate cancer than in white men.

“There are some genetic alterations that are not necessarily explained by prior treatment, but with the vast heterogeneity of such a population, and the lack of clinical annotation, it is likely due to other confounders,” Dr. Black said.

These results suggest that the ethnic disparities seen in men with advanced prostate cancer are likely not related to the biological differences in the tumor characteristics between white and black men, Dr. Black said.

Furthermore, these results showed that based on the treatment history of the study participants, black men were less likely to receive treatment in a clinical trial compared with white men.

Racial Disparities in Prostate Cancer Care

Dr. Mahal and colleagues also included a subgroup of 897 men with prostate cancer who had data from their treatment outside of clinical trials. Analysis of a genomic database showed that 91% of black men received treatment in the community compared with only 63% of white men. Receiving treatment in an academic setting usually means being enrolled in a clinical trial, where the newest therapies are being used.

“Notably, less than 10% of individuals with African ancestry were treated in the academic setting, whereas 37% of individuals with European ancestry were treated in the academic setting,” said Dr. Mahal.

The average age of black men was younger (66 years) compared with white men (68 years). Patients of African ancestry received an average of 2 lines of therapy before comprehensive genomic profiling compared with 1 line of therapy in white men, Dr. Mahal said, meaning that white men had genomic profiling earlier in the treatment than black men.

“African ancestry patients received comprehensive genomic profiling later in their treatment course than European ancestry men, after a median of 2 lines of therapy, compared with 1 line in European ancestry men,” said Dr. Mahal. “This difference is critical and important, and could ultimately impact the observed mutational landscape by ancestry.”

Although there were no significant differences in the use of targeted therapies, including PARP inhibitors, only 11% of black men received a new drug being investigated in a clinical trial, compared with 30% of white men. This difference could also affect the differences in mutational alterations, said Dr. Mahal.

“Are we making progress against disparities?” Dr. Black asked. “I think we are. We are giving this topic attention….But what is really important now is to take the next step and implement changes to achieve equity,” Dr. Black emphasized.

Dr. Black explained that these disparities in prostate cancer care underscore the importance of prostate cancer screening, genomic testing, and personalized medicine in black men in the United States.

“Data from these studies suggest that prostate cancer outcomes would be equivalent by race if we had timely diagnosis, adequate staging and risk stratification, and equitable treatment delivery,” said Dr. Black.

Key Points

- A large study shows that biological differences are likely not a major cause of differences in outcomes between black and white men with prostate cancer in the United States

- The number of men who are diagnosed with, and die from, prostate cancer varies by race, and black men with prostate cancer have worse outcomes than white men

- Black men received genomic profiling later in their treatment course than white men, which means they may not receive the best available treatment for their type of cancer

- These differences in diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer may explain the differences in outcomes between black and white men in the United States