About 10% of cancers are hereditary. That is, there is a genetic mutation in the reproductive cells of a parent that increases cancer risk. In families with hereditary cancer, a person inherits a mutated copy of a gene from one parent and a working copy of the same gene from the other parent. The working copy of the gene keeps the cells growing and dividing properly. However, if a mutation occurs in the working copy of the gene, then that cell can become cancerous. For this reason, people who have an inherited mutation have an increased risk of cancer in their lifetime, often developing the disease at an early age. Signs of a hereditary cancer include:

- Two or more relatives with the same type of cancer, on the same side of the family

- Cancer in several generations

- Cancer that occurs at an early age

- The same person has more than one primary cancer

The Discovery of Inherited Cancers

The French Physician and His Wife

Dr. Pierre Paul Broca, best known for his research on the brain and language, was the first to describe a family with many cases of breast cancer. In 1866, Broca reported breast cancer in 4 generations of his wife’s family.1 He also noted that his wife had breast cancer at a young age as did many of her family members. While Broca was the first to report that breast cancer could be passed from one generation to the other, it would be over a decade until scientists believed that cancer could be inherited.

The American Pathologist and His Seamstress

Like hereditary breast cancer, hereditary colorectal cancer was also first observed more than 100 years ago. Dr. Aldred Scott Wartin’s seamstress told him about her family’s long history of cancer deaths. Intrigued, Wartin studied her family, and found that many members had cancer in the intestinal tract and uterus. He also noted that in his seamstress’s family over one-third had cancer at a young age. Following Broca, Wartin’s report was one of the first to make the case that certain cancers were heritable in humans.2

Identifying The Genes

Despite the early observations of Broca and Wartin, most scientists believed cancer was caused by viruses. That is until Mary-Claire King, PhD, electrified the scientific community in 1990 when she published her study showing that mutations in a gene hiding somewhere on chromosome 17, which she called BRCA1, were linked to hereditary breast cancer.3

Mary-Claire King, PhD, electrified the scientific community in 1990 when her study showed that mutations in a gene were linked to hereditary breast cancer.

It would be 4 more years before the location and sequence of BRCA1 was known.4 Knowing the sequence of the gene revealed the specific mutations in BRCA1 in the families she and others studied. However, some hereditary breast cancer families did not have a mutation in BRCA1. In 1995, researchers found mutations in a different hereditary cancer gene called BRCA2.

In the mid-1960s, Henry T. Lynch, MD, reported on several families with a lot of cancer. He called these cancers Cancer Family Syndrome, which was later changed to Lynch syndrome. Lynch syndrome is the most common form of hereditary colorectal cancer, or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome.

Soon after the discovery of BRCA1, an international consortium showed that there was a gene hiding somewhere on chromosome 2 linked to Lynch syndrome.5 In 1993, MSH2 was identified.6 Again, not all families with Lynch syndrome could be explained by an inherited mutation in MSH2. Studying Lynch syndrome families who did not have an MSH2 mutation led, in rapid succession, to the identification of MLH1, PMS2, and MSH6.

Hereditary Cancer Misconceptions

Men can pass on an inherited mutation that increases cancer risk just as easily as women. If a parent carries a mutation, each of their children has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation and having an increased cancer risk. Each child also has a 50% chance of inheriting the working copy of the gene and having an average cancer risk.

Some hereditary cancer genes are linked to cancers that occur in only one sex, such as ovarian and prostate cancers. Even though these cancers occur in one sex, these mutations can be inherited from either parent. Mothers can carry and pass on inherited prostate cancer mutations; fathers can carry and pass on inherited breast cancer mutations.

Some hereditary cancers are specific to the sex assigned at birth reflecting organs present. For example, someone assigned male at birth with a BRCA2 mutation is at increased risk for prostate cancer; someone assigned female at birth with a BRCA2 mutation is not at increased risk of prostate cancer. However, both men and women have breast tissue. Because men have breast tissue, they can get breast cancer. While the risk of male breast cancer is low in the general population, men who have a BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2 and PALB2 mutation are at increased risk for male breast cancer.

Hereditary Cancer Today

With the identification of additional hereditary cancer families coupled with improved DNA sequencing technology, we now know that inherited mutations in many genes can increase cancer risk for many types of cancer. For example, BRCA1 was identified because of families with breast and ovarian cancer. However, we now know that inherited mutations in BRCA1 also increase the risk of pancreatic, prostate, and endometrial cancer.

Similarly, the first identified Lynch syndrome gene, MSH2, was originally considered a hereditary colorectal and endometrial cancer gene. However, we now know that inherited mutations in MSH2 also increase the risk of ovarian, stomach, and possibly prostate cancer.

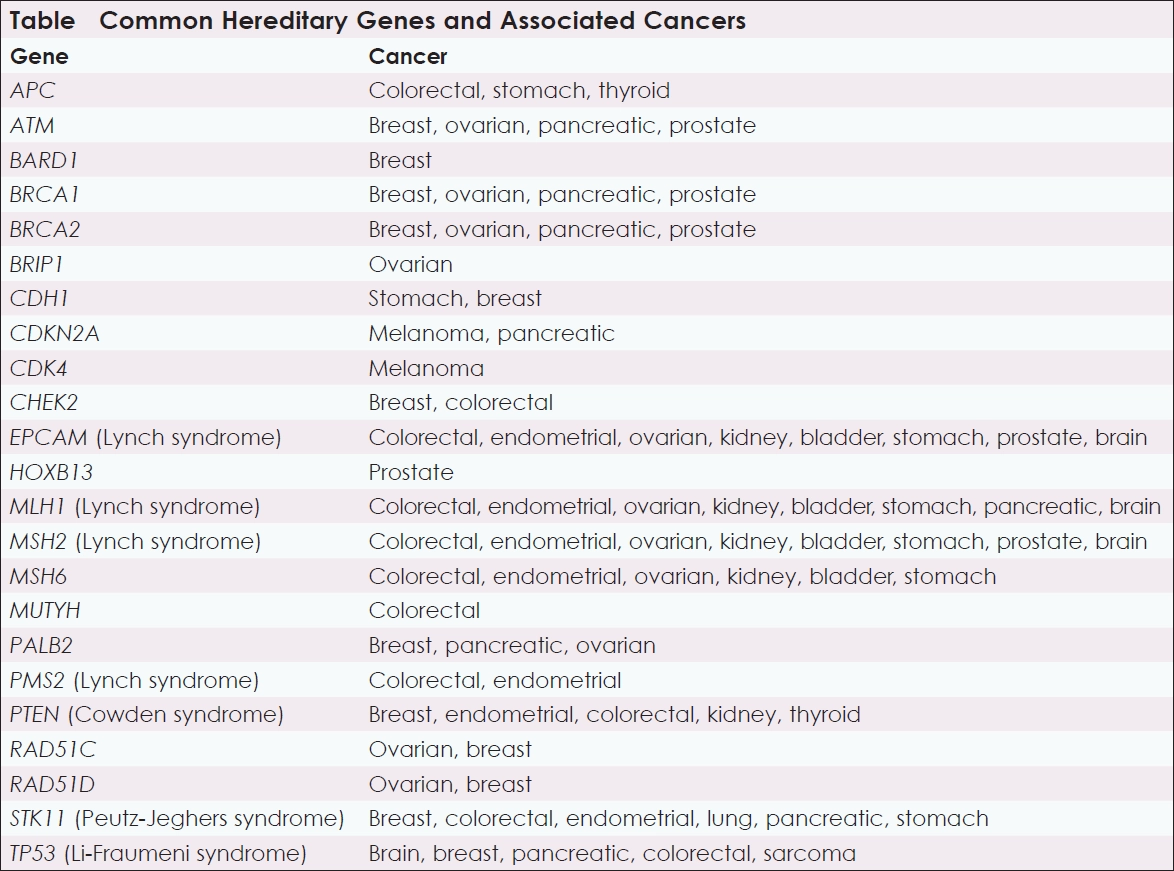

Today there are many recognized hereditary cancer genes that cause multiple kinds of cancers (Table).

Family History and The Future

About 25% of hereditary breast cancer is due to an inherited mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Other inherited mutations in genes such as PALB2, ATM, and CHEK2 explain another 20% of hereditary breast cancer. This leaves hereditary breast cancer unexplained for most families (over 50%) with a lot of breast cancer.

Hereditary colorectal cancer is similar. Currently, only 25% of all the familial colorectal cancer can be explained by inherited mutations in a Lynch syndrome gene or other colorectal cancer–predisposing genes like APC, BMPR1A, PTEN, SMAD4, and TP53. Much hereditary colorectal cancer remains unexplained.

Knowing your family’s history is important, especially if you are a member of a family with many cancer cases but no known genetic mutation. A genetic counselor can help you determine whether you should consider more frequent screening and/or consider other risk-reducing options.

Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered (FORCE)

As the director of patient education for FORCE, a national nonprofit organization, I am devoted to our mission of improving the lives of individuals and families facing hereditary cancer. If you and your family are facing an inherited cancer, you will find resources on the FORCE site to include:

- Peer navigation program

- Support meetings

- Message boards

- Helpline

- Healthcare provider locator

- Insurance/reimbursement help

- Clinical trial search and enroll tool

- eXamining the Relevance of Articles for You (XRAY) tool

In addition, FORCE hosts the Joining FORCEs Against Hereditary Cancer Conference to connect and empower individuals and families facing hereditary cancer. The conference includes presentations by hereditary cancer experts and offers participants a chance to connect with others with or facing hereditary cancer.

References

- Broca P. Traite des tumeurs. 1866.

- Warthin AS. Hereditary with reference to carcinoma: as shown by the study of cases examined in the pathological laboratory of the University of Michigan. 1895-1913. Arch Intern Med. 1913;12:546-555.

- Hall JM, Lee MK, Newman B, et al. Linkage of early-onset familial breast cancer to chromosome 17q21. Science. 1990;250:1684-1689.

- Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266:66-71.

- Peltomäki P, Aaltonen LA, Sistonen P, et al. Genetic mapping of a locus predisposing to human colorectal cancer. Science. 1993;260:810-812.

- Fishel R, Lescoe MK, Rao MR, et al. The human mutator gene homolog MSH2 and its association with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Cell. 1993;75:1027-1038.

About the Author

Dr. Piri L. Welcsh is vice president of education for the nonprofit Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered (FORCE). She completed her doctorate in molecular genetics at The Ohio State University and joined Mary-Claire King’s laboratory at the University of Washington to devote herself to the study of hereditary cancer genes. Dr. Welcsh is part of a family with high risk for breast cancer, but without a known mutation.