Meet Anna

Anna is a 67-year-old woman who was recently diagnosed with breast cancer in her right breast. More than 20 years ago, she was treated for breast cancer in her left breast with lumpectomy and radiation. She did not have any genetic testing at that time.

She has a video visit today with a genetic counselor to talk about testing for an inherited genetic mutation. Anna has a sister, a brother, 2 sons, 2 daughters, and several grandchildren. Her treatment team would like to wait for the results of the genetic testing before presenting treatment options.

Anna says, “I met with the surgeon yesterday, and she told me that based on the biopsy report, they will be doing some type of gene testing on that tissue. How will this test affect my treatment? Will it affect my family too?”

Genetics in Cancer

Genes are contained in the DNA of every cell in the body. Genes control how cells function, including how quickly they grow, how often they divide, and how long they live. To accomplish this, genes are involved in the creation of proteins; each protein has a specific function in the cell. The correct DNA sequence in the gene is essential to making a properly functioning protein. A mutation in a gene can potentially cause the creation of an abnormal protein or cause the protein to be absent altogether. Mutations can accumulate and cause cells to multiply beyond control, which leads to cancerous cells.

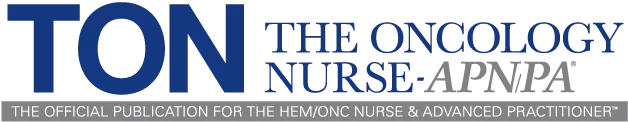

In cancer, it is important to recognize 2 types of mutations: somatic (also called acquired mutations) and germline (also called inherited mutations) (Figure).

Somatic Mutations

Somatic mutations, or acquired mutations, result from damage to genes in a cell over the course of a person’s life. These mutations can happen randomly, but more often they are associated with risk factors such as tobacco use, ultraviolet radiation, viruses, or just aging. Somatic mutations do not occur in every cell in the body and are not passed from parent to child.2

In cancer care, somatic mutations can be identified by testing the cancer tissue from a biopsy or surgical sample. The results from somatic mutation tests can help your treatment team determine the best treatment option for that specific type of cancer.

It is not routinely recommended for family members to undergo genetic testing based on results of somatic mutation testing. However, if test results reveal a mutation in a gene related to a hereditary cancer syndrome, then germline testing should be completed to confirm if the mutation is acquired or inherited.

Germline Mutations

Germline mutations, also called inherited mutations, arise in the sperm or egg cell, passing directly from parent to child at conception. If passed on, the mutation will be present in every cell of the body at birth. Although much less common than acquired mutations, inherited mutations can increase cancer risk significantly, as in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome related to the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.

In cancer care, germline mutations are usually identified by testing a blood or saliva sample. For breast cancer patients, the results from these tests can affect the treatment plan as well as uncover risk for other types of cancer and promote additional preventive measures. Certain family members may also be tested to determine inherited risk.

Anna’s Genetic Counseling Visit

During the genetic counseling visit, Anna learns more about genetic testing for inherited mutations. She now understands that the test performed on biopsy tissue is much different from the blood test to be completed today, which includes genetic testing of the BRCA1, BRCA2, and other genes included in a broad multigene cancer risk panel.

Anna asks, “Why didn’t I have genetic testing back when I had cancer the first time?”

The genetics counselor explains that the criteria for testing have changed since then. Around the time of Anna’s first diagnosis, BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing was only offered to women with a breast cancer diagnosis at age 45 years or younger if they did not have a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Today, the criteria have expanded to allow for more people to undergo testing, including women with bilateral or 2 separate occurrences of breast cancer, if the first diagnosis happened at age 50 years or younger. Also, pancreatic and some types of prostate cancer are now taken into consideration for testing in HBOC syndrome.

Two weeks later, Anna meets with the nurse navigator to review all test results to date. Tissue testing on the biopsy sample was completed and indicated that she may not need chemotherapy, but her genetic testing showed a BRCA1 mutation.

Anna shares her concerns, “I’m relieved that I may not need chemotherapy, but the surgeon is suggesting a more drastic surgery—removal of my breasts and ovaries. I’m also worried about my kids, especially my daughters. And I’m wondering if my sons need testing too?”

Who Should Have Genetic Testing?

The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends considering genetic testing for inherited risk in the following scenarios3:

- If a personal or family history suggests a genetic cause of cancer

- If a test will clearly show a specific genetic change

- If the results will help with diagnosis or management of a condition. For example, taking steps to lower risk that may include surgery, medication, frequent screening, or lifestyle changes.

Genetic testing in breast cancer has become increasingly complex. Multiple genes are now routinely tested, and the criteria for testing have expanded to allow more people to have access to testing. Genetic counseling before and after testing is key to ensure the appropriate tests are ordered and that the implications of the results are properly explained, regardless of whether a mutation is found. Ultimately, genetic testing is a personal decision that impacts not only the person with cancer, but their family as well.

Cancer genetic professionals refer to the guidelines established by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) for criteria on testing for specific genes that have a significant impact on care.4 These “high-penetrance breast cancer susceptibility genes” include BRCA1, BRCA2, CDH1, PALB2, and TP53. Most multigene cancer genetic tests include these genes. Women may be eligible for genetic testing if they4:

- Received a breast cancer diagnosis at age 45 years or younger (no family history required)

- Received a breast cancer diagnosis between the ages of 46 and 50 years and have multiple primary breast cancers and/or 1 or more close blood relatives with breast, ovarian, pancreatic, or prostate cancer

- Received a breast cancer diagnosis at age 51 years or older and have 1 or more close blood relatives with breast cancer at age 50 years or younger, male breast cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, or high-risk prostate cancer

- Received a diagnosis of triple-negative breast cancer at any age

- Have a personal history of breast cancer and are of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage.

Anna’s Test Results: What They Mean for Her and Her Family

Anna’s genetic counselor reviews the implications of her test results. Anna learns that having a BRCA1 mutation provides her with more options to reduce the risk of breast cancer recurrence and the risk of developing ovarian cancer. She plans to follow up with her surgeon to consider prophylactic surgical removal of both breasts and ovaries.

The genetic counselor recommends testing Anna’s close blood relatives for the BRCA1 mutation and inherited risk for breast and ovarian cancers, starting with her 2 daughters and sister. It is also recommended that her 2 sons and brother undergo testing for possible inherited risk for male breast cancer and prostate cancer.

Inherited Genetic Risk: A Family Affair

A known genetic mutation in a close blood relative is a clear reason to pursue genetic testing. People with a family history of cancer should meet with a cancer genetics professional to review their risk for cancer and determine their need for genetic testing. If someone has a first- or second-degree relative who meets the NCCN criteria listed above, genetic testing for inherited risk should be considered.

Anna: 1 Year Later

One year after her surgery, Anna comes in for a survivorship visit with her nurse navigator. Anna feels good about completing her aggressive treatment plan, saying “I’m glad I did everything I could to keep the cancer from coming back. I was scared at first thinking about the surgical removal of my ovaries too, but I have peace of mind now.”

One son and 1 daughter tested positive for the BRCA1 gene; both are following high-risk screening plans. Her daughter did not opt for surgical removal of her breasts and ovaries, but her mammogram and MRI are clear so far. Her son is 42 years old and will have yearly prostate cancer screenings and breast exams.

Anna says, “All my kids seem to be dealing well with all of this. My son and daughter have access to extra screenings. My other 2 kids have a little bit less to worry about, but they are still keeping up with their regular checkups.”

Advances in Genetics

Genetics in cancer care continues to broaden its impact as new discoveries continue to be made. In facing cancer personally, or in the family, your risk assessment for cancer needs to be an ongoing process. The plan for screening and prevention of cancers can change over time. Your cancer care team is a great resource to stay current on the state of the science in genetics. Genetic testing for inherited risk is unique due to its potential clinical implications, not only for the individual, but for generations to come.

References

- Cancer Support Community. Precision Medicine Plain Language Lexicon. www.cancersupportcommunity.org/PMPlainLanguage. November 2021.

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. Cancer.net. The Genetics of Cancer. www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/cancer-ba sics/genetics/genetics-cancer. March 2018.

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. Cancer.net. Genetic Testing for Cancer Risk. www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/can cer-basics/genetics/genetic-testing-cancer-risk. August 2018.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic. Version 2.2022. www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_2. 2022.

Pearls of Wisdom from Cancer Genetics Professionals

“Genes are like a recipe in a cookbook, they make something. The chromosome is the cookbook, and the gene is the recipe in the cookbook. Sometimes the genetic test results we get are like saying, we found a change in the recipe, but we don’t know if it messes up the cake OR makes it better. A change does not mean it is bad because you can change a recipe and make it better.”

—Cindy Snyder, DNP, ACGN, FNP-C, CBCN, on a genetic test showing an inconclusive result or variant of uncertain significance

“When you fish with a pole, you might catch a fish. But when you throw out a net, you are more likely to catch a fish. Panel testing is like fishing with a net.”

—Cindy Snyder, DNP, ACGN, FNP-C, CBCN, on multigene panels

“As a genetic counselor with over 25 years of experience, I always encouraged the patients I had the privilege to speak with to talk openly about their personal and family history with other family members and with their medical care team. Knowing your risk for cancer in advance allows experts to talk to you about risk-reducing strategies and even preventive measures. Cancer doesn’t mean a death sentence, and we ALL need to be aware of our risk and decide how best to handle that risk.

Knowing and sharing your personal and family history can save your life and the lives of your loved ones. Talking with your healthcare provider about your family history is a critical first step.”

—Shelly Cummings, MS, CGC, on the importance of personal and family history

Resources

Cancer Support Community: Precision Medicine. www.cancersupportcommunity.org/precision-medicine#understanding-genes-muta tions-and-biomarkers.

Facing Hereditary Cancer EMPOWERED. Improving the Lives of Individuals and Families Facing Hereditary Cancer. www.facingourrisk.org.

National Society of Genetic Counselors. Find a Genetic Counselor. https://findageneticcounselor.nsgc.org.